The Daily Blagueurs on Frappr!

(PS: I'm going to nudge this entry toward the top of the page for a few days.)

Hot on the heels of Joe.My.God, I have set up The Daily Blagueurs Frappr! Map. I hope that you will stick your pushpin in it.

« October 2005 | Main | December 2005 »

(PS: I'm going to nudge this entry toward the top of the page for a few days.)

Hot on the heels of Joe.My.God, I have set up The Daily Blagueurs Frappr! Map. I hope that you will stick your pushpin in it.

An old friend - all right, the oldest of friends (think Williamsburg. Agincourt. Lascaux.) - wrote to me privately today to say that, in his opinion, the people who commented on the other day's hissy-fit entry were "very brave." It is true that, had he, this old friend, made any remarks, there would have been nothing but a few bones and cinders on the plate when I was through. But to the rest of the world, I am the New Me! I have discovered the ultimate therapy: when I'm in a jam, I blog. I share.

Anybody who thought that I wasn't going to make my way down to A T Harris first thing yesterday morning to rent a tuxedo like a good boy gets a D minus. Do you honestly think that I could face my "innombrables lecteurs" if I succeeded in worming my way out of Thursday night's dance? Not on your life! I'd have had to close the site down and creep off in shame! The wonder of blogging, you see, is that I get to do the King-Kong thing and then, first thing next morning, distance myself from it. Tomorrow is another entry! In the end, I show myself to be capable of making a little sacrifice when it counts. Mind you, don't think that any of this faux magnanimity won points with Kathleen. She saw through it all from the start, responding to my Sunday-night imprecations with the "Yes, dear 101" technique. "I'm sorry," she'd say on the multiple occasions that called for this concession. "I'm so sorry." But that was all she'd say. Her beading progressed uninterrupted.

As if to make me even more ridiculous, the gent at A T Harris asked me if I lived in the city, in which case they'd deliver and then pick up. So much for my three trips.

My palsy being what it is, my proof-of-purchase will be valid only with those readers who (a) know what East 44th Street looks like, next to Brooks Brothers (on the right) or (b) trust me when I say that the number on the butterscotch marquee is "11." A T Harris is on the second floor.

During the transaction, I couldn't keep my eyes off the two manikins that were dolled up in Ralph Lauren. One suit was a tux, and the other was tails - as in "white tie and." It's only when you study such an outfit that you understand why it is that, in the language of proper invitations, the word "Informal," tucked into the lower right corner of the card, means that male recipients are to wear tuxedos. Happily for our less cryptic modern world, the term "Black Tie" does the job nowadays. Deny, if you can, that "Informal" was a mocking snare for the unwary. But when you contemplate the two possibilities side by side, it's true that the tux looks, well, casual.

We saw a marvelous show last week, on the night before Thanksgiving - that's why I haven't got to it sooner. It was Alan Ayckbourn's umpteenth play, Absurd Person Singluar. This was the sixth or seventh Ayckbourn that we've seen; it was by far the best. And for once, I have to begin by praising the director, John Tillinger.

Alan Ayckbourn is a master farceur. He knows more about doorways that the god Janus. He moves his characters - and their stories - with the precision of a clockmaker. He has a fantastic natural sense of humor. The problem comes in when he tries to be serious, to make a point. He does make a point in Absurd Person Singular: it is the point of the title. We're all absurd when all we think about is ourselves, as the six people in this play do. (The humor of "Absurd" is that, while it rhymes with "third," it refers to the first.) This is not a show that even an Olivier could muddle through without strong direction; the roles require exact synchronization. Mr Tillinger has directed lots of plays at MTC, including several by Mr Ayckbourn, but never has his choreography worked to such magnificent extent - a fact that I attribute to Mr Ayckbourn's staying out of the way. John Lee Beatty's amusing sets, Jane Greenwood's spot-on outfits, and Brian MacDevitt's superb lighting showed off the play's full comic potential.

The construction of Absurd Person Singular is elegance itself...

Continue reading about Absurd Person Singular at Portico.

Ms NOLA and M le Neveu returned from points north for dinner last night. We had a lovely meal at Maz Mezcal, but the nephew was so tired after driving in fog that he gladly accepted my offer of keys to return to the flat for a snooze while the rest of us talked. (Is he my father's grand nephew or what?) Giving him the keys was a brave gesture on my part, as Kathleen, Ms NOLA and I agreed that we would probably spend the rest of the night palpating the pavement of East 86th Street for dropped articles - but, no: the apartment door was open upon our return, and M le Neveu was stretched out on the living room sofa. The keys were symbolically draped upon the cashew canister.

The thing was, music was playing in the living room. It hadn't, I'll almost wager my life, been playing there when we left. The music that was playing when we left was playing in the blue room, as it still, gently, was. When I asked M le Neveu which particular buttons he had pushed, I was only curious. He, reasonably, was slightly defensive. "I only pushed that one," he protested, pointing to one of the two dozen remotes in the remote corral. At the same time, he was kind enough to say that the music (Radio RJ) was very pleasant. It was clear that he had wanted to turn on the television.

So that's what we did. We watched the tail end of Reno 911, and then The Daily Show and The Colbert Report. Kathleen was out of the room during the Daily Show segment in which Saddam Hussein was seen in a courtroom calling for a witness by the name of Amanda Huggankis. When Ms H was not forthcoming, the other personages in the trial went through a call-without-response for "Miss Amanda Huggankis." As in, "Oh why can't I find Amanda Huggankis?" It was so brilliantly puerile, so totally my own private sixth grade, that I am still weeping just typing. Telling Kathleen about what she missed was excruciating - for her as well, probably, if in a different way. "This is why we don't let RJ watch TV every day," Ms NOLA explained to Kathleen. I only wish.

Nothing that I am going to say about The Kite Runner (2004; Riverhead, 2003) ought to diminish in the slightest any reader's satisfaction in this extremely strong story of redemption and protection.

One of the blurbs on the back cover of Khaled Hosseini's first novel, from the Washington Post Book World, runs,

A powerful book ... no frills, no nonsense, just hard, spare prose...

It's not as hard and spare as all that, but The Kite Runner is one of the most artless novels that I have ever read, and I was quite confused by it until a possible resolution became clear, well past the half-way point. The Kite Runner turned out to be the very opposite sort of book from the kind that Miss G's remark led me to expect. "It's hard at the beginning," she said, while non-verbally challenging me to read a book that had meant a great deal to her. I assumed she meant that the story would be hard-going at first, difficult to read for some reason, such as violent subject matter or narrative obliquity. But it was the end of the book that I found hard: suspense overwhelmed my eyes to the point where they could hardly read.

But the novel remained artless right up to the last page. By this I mean...

Continue reading about The Kite Runner at Portico.

The other day, a new catalogue surfaced among the many regulars. "The Noble Collection: Holiday 2005" offers "Gifts and Treasures for the Season." Before my eye found the Lord of the Rings and Harry Potter logos at the bottom of the cover, I was wondering if this was some sort of Disney Dark offering. The castle on the cover, basking in moonlight, looked vaguely like Cinderella's, but the mood said "Vlad the Impaler." I couldn't tell if the castle was drawn or real. It's real - "resin," no doubt. Thirteen inches tall and perhaps slightly more than that square, this model of Hogwarts is yours for $295.

What would you do with it? Where would you put it? How long would it interest you? (It has no moving parts.) If someone gave you one, perhaps as a "gift for the season," what would you think the donor was trying to say? And what do you think it's going to look like in ten years?

I'm sure that there are jillions of Harry Potter fans who think that this architectural digest is more wonderful than any real castle. For them, happily, there is the actual Neuschwanstein, in deepest Bavaria, to look forward to. In the meantime, I hope that their parents and guardians find a better use for the three C notes.

What I want for my birthday, however, is this magnificent Revolutionary Guillotine Cigar Cutter. It's not only charming, but edifying, as well. Every time you use it, you can meditate on some hapless aristocrat, dragged from a burning château in her nightclothes... Or whatever lights your cigar. The cigar cutter is a steel at $97.50. Stainless steel, that is. Aren't good razors always?

There's nothing new about bad taste. There's nothing new about expensive bad taste, either. But I think we've reached new heights of expensive, mass-produced bad taste. I really am curious about the quality, too. There's a cunning collapsible Batman desk clock made of - well, it doesn't say. It does have a "High Polish Finish," however, and at four inches (collapsed), it won't take up much houseroom. Fully expanded, it can be priced at ten dollars the inch. Do you think I should buy it and find out how long the high polish lasts?

It has been a while since the last time my stubborn streak interfered with harmonious relations; I may even have been lulled into thinking that it had melted away. But it has me by the neck this morning, and when I'm not sulking, I'm furious. You don't want to have lunch with me today. Maybe not until next week.

Here's what I don't want to do: make three trips to A T Harris Formalwear, on 44th Street, to have measurements taken for, to pick up, and to drop off a tuxedo. I own a tux, but I've outgrown it, I'm sorry to say. It has been ten years or so since I last wore it. "Formal" events have ceased to be part of our lives, or at least I've successfully backed out of them. For some reason or other, Kathleen didn't give me the chance this time. Months and months ago, she accepted a friend's invitation. Done deal.

I left out the fourth trip: to a charity ball on Thursday night. I can't tell you how unappealing this sort thing seems to me. It didn't always. I used to like getting dressed up and going out. Maybe I still do, but I can no longer hear people in crowded, noisy rooms, and explaining just what it is that I do often draws odd looks.

Kathleen has offered (a) to go alone and (b) to ask another man to escort her. The very worst thing about this business is how tempting these offers are.

No, you don't want to be around me this week. For the first time in a while, I am very unhappy in my skin.

In which we have a look at this week's New York Times Book Review.

This week, there is a lot of interesting non-fiction. There is Bob Spitz's The Beatles: The Biography, enthusiastically received by pop authorities Jane and Michael Stern.

When the Beatles began, it would have been unthinkable to read a well-written biography about rock 'n' roll performers that was as serious and thoroughly researched as an important book about Faulkner or Picasso or Mao. For better and for worse, the Beatles changed off that. Their evolution sent shock waves radiating into culture and commerce as they took rock 'n' roll from the periphery to the mainstream and gave pop music a gravity heretofore unknown.

In the Sterns' opinion, Mr Spitz book is indeed such a serious and thoroughly researched book. It also had them hooked in ten pages.

Then there's Power and the Idealists: Or, the Passion of Joschka Fischer and Its Aftermath, by Paul Berman. According to Johann Hari, this book demonstrates that student unrest in the Europe of the late Sixties and early Seventies was much more than a matter of riots accented by terrorism. "Those were the rancid afterbirth of the street protests. The baby itself, [Mr Berman] writes persuasively, grew into a vibrant European antitotalitarian tradition." That seems right to me; I only wish that it had been the case here in the United States as well, but our hippies were far less serious about anything than their European counterparts.

There's Jesus and Jahweh: The Names Divine, by Harold Bloom. This book is right up my alley, except that Harold Bloom's prose style is deeply unattractive. Mr Bloom distinguishes sharply between Jahweh, Jesus of Nazareth, and Jesus Christ, arguing that they have nothing to do with one another, and he insists that there is no such thing as "Judeo-Christian" beliefs. I'd like a lot of my Christian friends to read this book. Joshua Rosen's review may just have to suffice for me.

Three books explore important black American careers. First is Jill Watts's Hattie McDaniel: Black Ambition, White Hollywood. Hattie McDaniel was the first African-American to win an Academy Award; reviewer Dana Stevens doesn't say so, but I've read that, in order to get into the Coconut Grove at the Ambassador Hotel to receive the award, the actress had to pass through the kitchen. The dilemma facing all black entertainers until very, very recently, was whether to be true to their black roots or to work at all, at a time when working meant caricaturing themselves. Hattie McDaniel worked out a compromise, but it was not good enough for many in the NAACP, and her Oscar didn't do her much good. (She got to reprise the role of Mammy in The Great Lie, an underrated Bette Davis vehicle.) Mr Stevens reviews this book together with Mel Watkins's Stepin Fetchit: The Life and Times of Lincoln Perry. Perry was an altogether less attractive person, grandiose and deferential at the same time. He appears to have owned a pink Rolls-Royce with his name spelled out on the boot hood - in neon. That must have been one of the earliest automotive applications of an inert gas.

A more redoubtable black American is the subject of Mirror to America: The Autobiography of John Hope Franklin. Mr Franklin has combined scholarship and ardent advocacy over a long and eminent career. David Oshinsky writes,

Franklin has studied his nation for nearly three-quarters of a century. His scholarship tells us that people must be judged by their willingness to remove the obstacles and disadvantages that oppress society's most vulnerable members. His conscience reminds us of how much remains to be done.

Now for the books that are not on my list. The Monster at Our Door: The Global Threat of Avian Flu, by Mike Davis, has the misfortune to appear at a time when almost everybody is singing in the choir of the converted; the question is what to do, not whether to do something, and books such as this can't be saved even by the great writing that reviewer Matt Steinglass finds here. Nor am I going to read Imperial Grunts: The American Military on the Ground, by Robert D Kaplan. David Lipsky astutely captures the problem with Mr Kaplan's thinking, which I'd noticed myself in various articles in The Atlantic: Mr Kaplan likes war.

Toward the book's end, Kaplan reflects that no to have participated in some kind of war was to be "denied the American experience," to be "not fully American." He continues, "the war on terror was giving two generations of Americans vivid memories." This might strike a reader as a somewhat more cosmopolitan notion that anything the elites could cook up at their "seminars and dinner parties." War as self-enhancement, as an experience not-to-be-missed. "The American experience," Kaplan writes, "was exotic, romantic, exciting, bloody and emotionally painful, sometimes all at once. It was a privilege, as well as great fun, to be with those who were still living it."

You can't beat that for catastrophic wrong-headedness - I hope. In his front-page review, John Simon argues that Richard Schickel's Elia Kazan: A Biography, is a book not-to-be-missed. Kazan made a lot of important pictures, among them A Streetcar Named Desire and On the Waterfront, but I've never really liked them, and the review suggests that the director was far too involved in issues of "manliness" to appeal to me.

According to Gregg Easterbrook, Benjamin M Friedman fails to make the case, in The Moral Consequences of Economic Growth, that liberal democratic society requires constant growth. That's all I needed to know. Richard Sandomir pulls of the stunt of making David Halbertstam's The Education of a Coach sound interesting to me - but the review of this new book about Bill Belichick will have to do.

There are only three novels in this week's issue. The Jungle Law, by Victoria Vinton, is about Rudyard Kipling's sojourn in Vermont. Mark Kamine's review failed to rouse my interest, as did Wendy Smith's look at Robb Forman Dew's latest, The Truth of the Matter. Both novels appear to be rather well-done, but just not to my taste. John Banville's The Sea is more problematic. A few years ago, I read and disliked another novel by Mr Banville, Eclipse. If reviewer Terrence Rafferty is to be believed, The Sea is a somewhat different production, at least at first. As it goes on, however, it reverts to Mr Banville's natural style.

What's strangest about The Sea is that the novel somehow becomes simpler and clearer as it gets more self-conscious: a consequence, I suppose, of its author dropping the pretense of being one kind of writer and giving into his authentic and much more complicated creative nature.

There is no Essay this week, just a Rick Meyrowitz cartoon suggesting the books that "hatchet job" Dale Peck might have given us instead of the "genial fantasy for children" that he actually wrote. They're almost all delicious: How to Cook Your Editor, Liizzie Borden Was An Amateur, Murder at Churlish Peeve, and The Twelve Stupidest Vegetables in My Garden.

Finally, in "Poetry Chronicle," Joshua Clover and Joel Brouwer review ten new collections. Of Mr Clover's five, two stood out for further exploration: The Life of a Hunter, by Michelle Robinson, and Company of Moths, by Michael Palmer. I'll let you know. Heather Fuller (Startle Response) David Baker (Midwest Eclogue) and Arthur Sze (Quipu) will require further advocacy. Of Mr Brouwer's five, the same outcome obtained: Simone Muench's Lampblack & Ash and Brian Turner's Here, Bullet got my attention; I had already heard good things about Mr Turner's verses on the themes of our Iraqi misadventure. Elizabeth Alexander (American Sublime), Adrian Castro (Wise Fish), and Patricia Ferrell (Thirty Years War) didn't catch my eye. I won't say more, because it's idiotic to measure a poem by extracts from a review. I don't know how grateful these poets will be for their somewhat crammed exposure.

Every now and then, I make a mistake in a bookshop. I buy something against my own better judgment. I can count on one hand - one finger, perhaps - the times that buying a book against my better judgment hasn't led to disappointment. If I remember correctly, the last time that this happened, I allowed myself to be persuaded by Lenox Hill Book Store proprietor Jeannette Watson's pitch to another customer; perhaps I deserved what I got for eavesdropping. The book was The Da Vinci Code. Empty calories! Not only did I dislike the book, but my respect for Ms Watson dropped a bit, too.

After a certain procedure late last month (see the entry for 27 October, but don't say I didn't warn you), I did not call Kathleen to tell her that I was fine, as I was supposed to do, but, still somewhat dazed - feeling okay, but not a hundred percent grey-matter-wise - wandered instead into Shakespeare & Co's Hunter College branch. Memo to self: don't buy books on anesthesia. Piled on a table of recent paperback releases, A Weekend at Blenheim, by J P Morrissey, roped me in. The blurb from Dominick Dunne on the back cover signaled that the book would be light entertainment at best, but the opening paragraphs read nicely enough, and the packaging did promise a visit to the most formidable of England's stately homes.

I visited Blenheim with my father, in the summer of 1977. We were driving from London, through Oxford, to a hotel not far from Birmingham where he and my mother, who had just passed away, had enjoyed a stay some years earlier. Woodstock was on the way, so we pulled in for a look. There was no question of going indoors. The baroque bulk seemed rather urban for the gentle countryside, but it was handsome nonetheless, and the slope from the water to the Great Court was a nice stroll. My memories of Blenheim are pleasant enough.

The Blenheim of Mr Morrissey's novel, in contrast, is malign.

Its monstrous square towers and commanding arcades gave the palace a romantic, medieval air, as it it were a fortress high on a cliff over the Rhine or along the road to Damascus.

Built with a grant bestowed upon a victorious general - "war money" - it is more mausoleum than home, a prison for the dukes and duchesses who must somehow keep it up. The current, ninth, duke of Marlborough - the story is set in the summer of 1905 - has married very well, if not for love, in order to pay off debts and repair the fabric of his ancestral pile. His duchess is the former Consuelo Vanderbilt - and the future Mme Jacques Balsan. Other real folks on hand for a country-house weekend are the duke's first cousin, Winston Churchill, and the duchess's mother, Alva Belmont. So is the duke's mistress and future wife, the American Olive Deacon. Rounding out the party are John Singer Sargent and a Monsignor Vay de Vaya. These people are used to living in the presence of great power, and they're all - even the Monsignor - very sophisticated. If you want to know more about them, Wikipedia is a good place to start.

Into this Edwardian scene are introduced John Vanbrugh, a young American architect, and his English wife, Margaret. Margaret is the daughter of the local vicar, and the duchess, intrigued by the young man's name, which is the same as that of the architect of Blenheim itself, has decided to hire him to "do some work" on her private rooms. (This project never sounds plausible for a moment.) At first charming, thoughtful, and even adorable, the duchess eventually shows herself to be worldly and calculating, willing to do anything to preserve appearances. In the course of less than forty-eight hours, John goes from protectiveness through worship to disenchantment. To say more would spoil the story.

Throughout the book, I thought how much better A Weekend at Blenheim would be if it had been written in the third person. Van's narrative voice is annoyingly fussy. His middle-class Yankee's first impressions of English stately grandeur are predictably obsequious and naive. His respectability is especially tiresome. With a little more art, and rather more acid, too, Mr Morrissey might have turned his hero into a very unreliable narrator, a sort of dry Charles Pooter. As it is, Van simply doesn't know his own mind on the subject of Blenheim. He thinks he hates it, but he can't stop describing it in minute, enthusiastic detail.

She left our group and turned to the duke, who was standing with Mr Sargent, who looked troubled. She whispered something to the duke, and a flash of irritation crossed his face. At that moment the butler announced dinner, and as a group we proceeded to the dining room, which had been simply but exquisitely arranged. A crisp linen tablecloth, two silver vases spilling over with white orchids, two tall bronze candelabra, their red candles covered with small opaque shades; the china rimmed in scarlet, turquoise, and gold; the myriad crystal wine glasses and sparkling silverware - all contributed to the beauty of the table.

It's paragraphs like that that make me long for Henry James's obliquity.

Another, related, failing of the narrative voice is that it is characterized by a sort of intervening amnesia. The illusion of the first person story is that the writer is reporting events that occurred in the past. Presumably the intention is to show how things came out. Mr Morrissey's narrator, however, seems to be genuinely unaware of what is going to happen next. This is necessarily true of the character in the story, but it makes the reporting narrator look very, very stupid. There is no irony, no foreboding, no intimation of the denouement. As a result, the plot begins to look like an excuse to linger in an ohh-and-ahh environment.

A longer discussion of this novel would explore the hypocrisy and contradiction of Van's marriage - or, rather, the strong impression that Van is notaware of them. (More stupid.) There are moments when he seems ready to run off with the duchess, although in a strangely platonic way. If Margaret weren't pregnant, I'd wonder if John's friends and relations failed to tell him about the facts of life.

Much of A Weekend at Blenheim is thoroughly delightful. Mr Morrissey appears to be in thorough command of his history as well as of his architecture, so much so that I wonder if the novel might be a metastasized dissertation. It is always very agreeable to read about lively figures who really trod the earth. Mr Morrissey's Winston Churchill, still a bachelor in 1905, is always a welcome voice, and his cousin is humorlessly dim. Miraculously, for an historical novel, nobody says anything noticeably anachronistic - although I do question "soul mate," perhaps mistakenly. "Downstairs" life, insofar as we see it at all, takes place upstairs, in the attics of "Housemaids' Heights." But I may as well say that I was grateful for the nice photograph of Blenheim's rooftops in Country Houses from the Air. It turned out to be helpful for following the novel's somewhat unlikely climax.

There's an old saying - well, not that old - that when you see married couples having lunch on a weekday, it's because they're on their way to the divorce lawyers. This always makes me chuckle, on the rare occasions when I do have lunch with Kathleen on a weekday. It doesn't happen often.

And it happened only accidentally today. When I got up at 9:15, I was surprised to see that Kathleen was still asleep, since she'd told me that she was going in to the office. I decided right away that I was going to go see Derailed across the street at ten, and when I left the apartment, Kathleen was reading the Times. Walking home from the movie - there is nothing that can be said about Derailed except: Clive Owen owns this film; he makes you forgive its creaky plot points over and over and over again; and "See this thriller!" - I wondered if I would find my dear wife snuggled up under the covers. It turned out that if the movie had been a half hour shorter, that's just what I would have found. Coming into the lobby when I did, however, I ran into my Prof's wife, and we were talking about La Côte Basque when Kathleen slunk into view. She said that she was on her way to lunch, and, after introducing her to Mme Prof, I invited myself along. We went to Burger Heaven, where we sat and talked for a long time, although not about divorce. On the contrary. We talked about how blogging has cleaned up my life. Ordered it and made it work.

But just now I'd rather talk about La Côte Basque, or, as it appears to be styled nowadays, LCB Brasserie Rachou. (The last part refers to chef-owner Jean-Jacques Rachou.) "LCB," which I find I automatically pronounce as "Ell-Say-Bay," seems quite arch, since it can't mean anything unless you know the name of the restaurant that, prior to last year, occupied the same space. La Côte Basque was one of New York's premier "temples of gastronomy," very grand and very expensive. Kathleen and I went perhaps six or seven times over twenty-odd years, almost always to mark a birthday or an anniversary. But the grand old French restaurants are no longer popular, and for the most part they've closed. M Rachou is to be applauded for coming up with an attractive, and, I hope, successful rethink. The quaint old murals and the Louis Quinze chairs have been retired (the Villeroy & Boch "Basket" is still in use, however). The new color scheme features a distinctive ocher mustard, with black trim. The walls have been lined with mirrors and adorned with belle époque light fixtures (with frosted glass shades) and amusing medallions of sporting folk circa 1900. There are even more banquettes than there used to be, which is very good, because - the only design error - the unupholstered bentwood chairs are almost shabby and obviously not comfortable. The floor has been covered in small tiles.

Other diners were presented with the full menu, but we, for some reason, were not; nor did we mind. The holiday menu was just fine, even though it didn't announce just where the prix had been fixed. (The figure turned out to be "$50" - extremely reasonable.) Kathleen chose salmon tartare, sea bass, and pumpkin pie. I went the supplemental route ($3.50 tacked onto each dish) and had crabmeat salad, filet mignon Périgourdine, and the restaurant's signature Grand Marnier soufflé. Everything was great, but the Périgourdine sauce was sublime. Complex but elemental, it was the earthiest thing that I have ever tasted; it was as though the meaning of existence could be packed into an exotic mushroom. Well, why not? It was. Thanks to an amuse-gueule of pumpkin bisque, we could hardly clean our plates, but I struggled manfully with that sauce (one slice of filet would have been enough). Almost as extraordinary was the bottle of wine that I chose, Lynch Bages 2001. Two glasses of Pauillac were enough to put Kathleen to sleep, but she managed to get home under her own steam, or at least with her head on my shoulder in the taxi. And so our luxuriously quiet Thanksgiving Day crept into the night. We hope that yours was just as warm.

The featured Essay in the current issue of Harper's, Erik Reece's "Jesus Without The Miracles: Thomas Jefferson's Bible and the Gospel of Thomas," would be an arresting read at any time, but in coming at the time of national thanksgiving it packs an even mightier punch. Briefly, Mr Reece, the lapsed son and grandson of Baptist ministers, traces an unexpected connection between the version of the Gospels that Thomas Jefferson knocked off by removing everything miraculous and entitling the result, The Philosophy of Jesus of Nazareth, on the one hand, and the Gospel of Thomas, an non-canonical writing, probably older than the canonical ones, that was unearthed in 1945 at Nag Hammadi in Egypt. These documents are far too concerned with what Jesus said to be called "Christian." Christianity is a carapace built around the figure of Jesus that also obscures him; it stands in the same relation to Jesus as one of Tutankhamen's glorious coffins does to the young king's mummy. Χρίστος - "Christ" - is the Greek translation of "Messiah," something that Jesus did not claim to be. It represents the fabulous constructions of Paul and his followers. Most important doctrines, from the Trinity and the Immaculate Conception through Original Sin and the Resurrection, completely lack the authority of Jesus' word. They are the mainstays of a formidable institution that has served a majority of Westerners well enough while crushing and maiming those who question its authority, which it claims to derive directly from God, in the person of Jesus. I doubt that Jesus would have much good to say about its non-charitable operations.

It is not surprising that the Gospel of Thomas was declared to be heretical in the second century, and that copies of it were ordered to be burned. It is not surprising that the Apostle Thomas's best-known appearance in the canonical gospels, at John 20:24-29, discredits him as lacking faith in Jesus' resurrection; at the time that the Gospel of John was written, the Gospel of Thomas was probably still in circulation and increasingly disputed. These are not surprising because the Gospel of Thomas, like The Philosophy of Jesus of Nazareth, is wanting in miracles.

Continue reading about stewardship at Portico.

It's hard to believe, but the computer tells me that I haven't told this story here.

Two years ago today, we were in Paris. Kathleen was convinced that the only way we could get out of sharing turkey with friends and relatives was by leaving the country. So we checked into the Park Hyatt in the Rue de la Paix. It's a great little hotel, but I hope that they have a new chef. Do you really want to eat a club sandwich that has fava beans in it? No, I didn't think so.

Park Hyatts, wherever they are, are super business hotels, very quietly luxe. The concierges are always très fiable. They'll get you where you want to go. Even so, I was truly surprised when we were told that we had a table for two at Taillevent, one of the most remarkable restaurants in the world, on Thanksgiving Day. As JR at L'homme qui marche has noted, this is just another Thursday in France; you go to work today and you don't faire le pont tomorrow. We thought that having Thanksgiving dinner at Taillevent would be our own private Idaho. But, no.

We were not seated in the inner sanctum. My mother-in-law would have complained about the table - not that it would have done her any good. One hears that there is a quota system at Taillevent: no more than forty percent of the diners can be foreign. Nevertheless, we were very happy to be where we were. I believe that I had lamb, because I remember a brief conversation with the genial patron afterward, in which he told me that the lamb came from the Pyrenees. But what I remember most clearly is what happened across the room at a table for two.

Two. Because of my stiff neck, I didn't get a good look at the couple, but as I recall it was composed of a prosperous gentleman and his niece. She at any rate couldn't have been a hearty eater.

A waiter rolled out a metal table on wheels, one of those fancy "hotel silver" affairs, on which there was a large silver cloche. This got everyone's attention. When the waiter got to the table across the room, he whisked off the cloche to reveal a full-sized roast turkey. After slicing a few pieces of meat from the breast of the bird and serving them, he wheeled the largely-intact carcass back into the kitchen in unmistakably embarrassed haste. It was only the sophistication that all Taillevent guests must possess that kept the room from bursting into applause (or laughter), for you may be sure that no one in the room did a thing but stare at this incredible production. Need I say that roast turkey was not on the menu?

We asked our waiter, and were discreetly assured that the gentleman was "not American." Even so, it was the best floor show that I'll ever see.

Because of the Times Select paywall, I have not supplied links to the writings discussed in this entry.

As befits the eve of our annual fête de food, yesterday's Times Op-Ed page is given over to three essays on the state of the national cornucopia. Farmer Nina Planck urges us to look beyond claims that food products are "organic" for proof that say, beef is "grass-fed." This is because food giants such as General Mills have acquired "organic" brands and now, as members of industry associations, are lobbying to relax some of the restrictions.

Unfortunately, the organic rules are all but silent on the importance of grass to animal and human health.

Chef Dan Barber urges us to change our diets, not only for our own health but also to encourage mid-sized farms by consuming less of the mega-crops - corn, soy, and sugar.

We're going to have to support a diet that contains fewer processed, commodity-based foods. We're going to have to pay more for what we eat. We're going to have to contend with those who question whether its practical to reduce subsidies for large farmers and food producers. And we're going to have to reward farmers for growing the food we want for our children.

Finally, New Orleans professor John Biguenet writes with disgust of the national stinginess that has driven many in his city to wonder if it will ever be viable again.

So far, the president, Republican leaders in Congress and even the reconstruction czar, Donald Powell, have declined to provide any commitment beyond repairing the levees already breached. But if the United States refuses to protect New Orleans, what will the world - and what will history - make of a nation that let one of its most celebrated cities die?

There is also a silly column by Thomas L Friedman, urging the president to change course. What I can't understand is Mr Friedman's faith that this is possible. If there's one thing that I can't be thankful for, it's that the United States has been well-served by democracy in recent years. Because it hasn't been.

What all four pieces point to is the importance of responsible stewardship in human affairs. That's a topic that Eric Reece addresses with surprising force, and from a surprising direction, in an essay that I will write about later today. Meanwhile, Happy Thanksgiving to all my countrymen, at home or abroad.

Changing course on the travel front left me rudderless yesterday. I can't remember the last time I accomplished so little on an otherwise free schedule. Eventually, I made myself sit down and read The Kite Runner, so that I could tell Miss G how far along I am. In the event, I forgot to mention it. When I see her next, I'll have finished the book. And our next meeting may be sooner than later. If the musicians are good, she'll want to take us to the Village Vanguard a week from Friday. It's curious: Kathleen and Miss G both love jazz, but while Kathleen has never been to the Vanguard, Miss G has never been to the Blue Note. There's something very NYC about that. (I appreciate jazz deeply, which is different. I love Mozart and Schubert)

Miss G was delighted with the scarf that Kathleen gave her: she has elected Kathleen as her source for scarves. Kathleen has an extraordinary eye for color - for absolute color, even - and she also picks up people's coloration. She knows what colors will look good on someone and and she knows what colors someone will like. The last scarf that Kathleen gave to Miss G was one of the many that she brought back from Istanbul, and Miss G was floored one night when someone asked her if she'd gotten her scarf in Turkey. For a moment, she couldn't make the connection: how had she come into possession of a Turkish scarf?

My gift was less certain to succeed: a couple of books about cities, and Geoff Dyer's The Ongoing Moment, which I'm going to get for myself when I've cleared a little space. (See last Sunday's "Book Review.") I had just spotted it at the St Mark's Bookshop, along with a recording of John Ashbery reading his own poems. I'd read in The New Yorker that people often say that Mr Ashbery's poetry makes more sense to them after they've heard him read it, so I'm giving that a shot. In my opinion, all books of poetry ought to be recordings. I can't tell you what hearing Wallace Stevens read "Credences of Summer" does to me.

Dinner at Jules was good as always. We had a bottle of Château Loret, I think - it's the wine from Cahors that I always order. Miss G and I split an order of interesting but delicious steak tartare, and then I had half of a small roast chicken. The chicken was a little dry; I suspect that it spent some time waiting in the kitchen, because the delay between courses was unusual. The ladies had tuna. We sat in the back, where the live jazz is still quite loud but not too loud for conversation, and between us and the music there was a table of five young French persons, deux gosses et trois gonzesses. I could not make out a word of their animated conversation, but, as Kathleen pointed out, I wasn't supposed to be listening to them. It's frustrating, though, because despite all my work (hmmm), the casual exchanges of native speakers remains so opaque.

Boy, was it cold when we came outside! The wind was downright nasty. We walked Miss G the few blocks to her building, but Kathleen declined the offer to pay a visit upstairs, because she has a big conference call this morning and wants to be fresh. I was tuckered out, too, after my day of doing nothing much beyond eating well and accumulating books.

Can I really be the father of a beautiful thirty-three year-old woman? Yes, thank heaven, I can.

As a rule, I don't talk about our travel plans much, because they're likely to fall through at the last minute. The trip to Paris and Amsterdam that we proposed for earlier this month fizzled out sometime in October, making me glad that I hadn't really written anything about it. But even I was surprised, yesterday, when our Thanksgiving Day trip to Puerto Rico became untenable.

There were two culprits. First, there was - is - will be - Hurricane Gamma. According to weather reports, we would be spending our days by the sea under a more or less permanent cloud of rain. That would more or less defeat the purpose, at least for Kathleen, because she really needs the sun right now. The second factor was a combination of the Securities and Exchange Commission (I can say no more than that) and the lack of high-speed Internet connections in the charming casitas at Dorado Beach. (There is, apparently, wi-fi, but Kathleen and I haven't got that far in the alphabet, as Mrs Grimmer would say. Wireless communications don't work in plastered Manhattan apartments.)

At first, I suggested that we postpone the trip a week. But that would interfere with an annual convention that Kathleen never misses. As it happens, the convention is always held in, or just outside of, Phoenix, where the sun shines in a reliable manner at this time of year, so it didn't take screwing in a light bulb for me to suggest that I might accompany her for an extra couple of days before or after the convention. The convention usually takes place at the Biltmore, designed by famous small-person Frank Lloyd Wright - he must have really loathed people of my height, because he certainly created spaces that make me truly uncomfortable - but, this year, it has been moved out to the edge of Scottsdale, to the Hyatt resort at the Gainey Ranch.

So, no sleeping to the sound of surf. A real bummer, that. I will say right now that I have no desire to spend a week in Arizona. Those mountains and open spaces out west - they make me ask if this is still my country. Don't they belong in Mexico? (Yes, they do.) I share with the late Bourbons an idea that nature is very fine in its place - and that it's up to me to decide where that place is. There is something rude and impolite about mountains. It's fine when they're ornamental, as they are in Hong Kong and San Francisco. But there ought never to be more than five or six.

Now, what to do about Thanksgiving? The Puerto Rico trip evolved out of a passionate desire to escape this holiday. We hate the menu! Everybody we know will be somewhere else, which is good for them, but it's a bit demoralizing to spend holidays at home, pretending that they're days like any other. Can anybody recommend a restaurant that, at this late date, has a table for two?

Looking back a bit, I see that I haven't written much about politics lately. There hasn't been much occasion to do so, or so I've thought. But the echo of last week's "Mean Jean" Congressional outburst, which I heard by chance on the radio, has been hard to shake. It reminds me that, while I'm waiting for the Democratic Party to be replaced by something more constructive, the political scene becomes ever more malignant. How far off our rocker can Bush & Co push us? Given time, I am certain that it could and would destroy the United States of America and every man, woman, and child in it. No point in saying that every day, however. So I'll let Ellen Moody have the floor.

Politics? I don’t write politically regularly. Well, while the present US administation is so egregiously, shamelessly brutal, doing all it can to grind down the vast majority of people in the world for the benefit of a very few; torture is now open and institutionally encouraged; soon many more US women with no money or wherewithal to leave the states may have to endure compulsory pregnancy (admittedly many don’t seem to mind; this way they hope to nail some man to them?); but this is really more of what’s been developed by US institutions since WW2. Bush did get enough votes to steal the two elections. I am literally sickened and disgusted—amused too as they're clearly dangerous and absurd—by the gross SUVs which make driving harder, and parking a nightmare: you can’t see over or beyond them. Road pigs, no warts getting fatter and taller every year; yesterday at Kaiser’s parking lot two couldn’t get past one another in a lane.

The world we have is the world human beings as a group allow, seem to want.

Is it the world that you want?

Patricia Storms, of Booklust, was invited to participate in a CBC radio program that aired yesterday. Hosted by Rex Murphy, it's called Cross Country Checkup. Patricia talks about two books dear to her heart (one of which is very dear to Kathleen's as well), and she explains what a Web log is as well as anybody has ever done. Patricia's segment, which lasts about ten minutes, begins at about 56 minutes into the show, so push the ball along the Real Audio line to there to hear one of my favorite bloggers.

Thursday night, I walked a couple of blocks to Holy Trinity Church, the bold quasi-Gothic spire of which is part of the view from the window to my right. In 1987, the church inaugurated a new Rieger pipe organ, situated at ground level in the right transept, with a console visible to about half the nave and all of the left transept. Being able to see the organist makes organ recitals a good deal more interesting, if less mystical.

And what I learned, or figured out, or finally realized, on Thursday night, was that you can be a petite ginger-haired septuagenarian and make the instrument roar without breaking a sweat. I have never seen so relaxed a performing musician as Dr Alain. Her hands played with the same feathery motions regardless of the sounds they were called upon to produce. A similarly disengaged-seeming pianist would probably be hospitalized for observation.

I must confess to the surprise of discovering that Dr Alain is still alive, much less ...

Continue reading about Marie-Claire Alain at Portico.

Today's word is actually a pair of homonyms. They have come to share the same spelling: caddy.

There is the golf caddy, formerly a human being, formerly a "caddie." This word comes, via Scotland, from the French cadet, or young man. Specifically, a young man who would hang about, available for brief hire as a messenger. This meaning was set by the early eighteenth century. Printed references to golf caddies date from the 1850s.

Then there is the tea caddy, derived from a South Asian measure of weight used for tea, or catti. Eventually, the container took the name of the measure. A tea caddy is a small box made of wood or porcelain. Tea caddies became merely decorative vessels when people began brewing their own tea in their own kitchens, instead conducting the whole elaborate (and inconvenient) operation at a tea table in the drawing room.

All of this was brought to mind by a small porcelain cache-pot that I bought for Kathleen at Tiffany a thousand years ago. It's really much too small for anything but a minute pot of African violets, and for years it has held items that approach two dimensions: ticket stubs, business cards, and bookmarks. Going through its contents last night, it occurred to me to call it - the cache-pot - a caddy, and I wondered why. I think that it's some subterranean confusion of the two words, caddie and caddy. It's small, like a caddy, and it helps out by carrying things, as does a caddie.

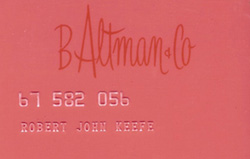

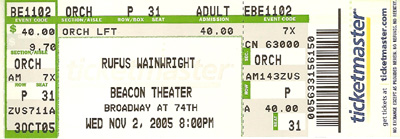

The ex-cache-pot now holds (a) bookmarks, (b) a small magnifying glass in the brocade envelope it came in, at China Arts & Crafts in Guangzhou, (c) a map of Bermuda, together with a plan of the Dorado Beach/Cerromar campus that we'll be heading off to (in Puerto Rico, not Bermuda) on Thursday (didn't have to hunt for that!), and (d) a few miscellaneous items - who's perfect? The ticket stubs are in a box of their own, while the old credit cards, of which that for B Altman, above, is my favorite, not because of the color but because of the store itself, which was everything that a department store ought to be, are in a "souvenir" box that will probably fill up faster than I want it to. But everything looks neat.

In which we have a look at this week's New York Times Book Review.

Nonfiction first, shall we? Alan Riding reviews Benedetta Craveri's The Age of Conversation this week, exactly two months to the day after my enthusiastic entry. The call-out pretty much summarizes Mr Riding's casual grasp of Ms Craveri's important book: "It was shrewd: Parisian women invented a social game where they set all the rules." On the facing page, Jonathan Alter dismisses Mary Mapes's attempt, in Truth and Duty: The Press, the President, and the Privileges of Power, to explain away her disastrous rushing of the Texas National Guard story in last year's run-up to the election. Although the substance of the story about the President's shirking, during the Vietnamese War, was probably true, the slipshod documentation opened the door to right-wing attack. Even Dan Rather had to resign in the end. If I were Ms Mapes, I wouldn't be writing about my professional competence.

Roy Blount Jr, a funny man from the South whose humor usually eludes me, writes up Richard Porter's Crap Cars, a catalogue of the fifty worst cars ever made in modern times. Mr Porter writes with great brio, which more or less salvages his project from fatuity. According to John Leland's review of Dream Boogie: The Triumph of Sam Cooke, by Peter Guralnick, the versatile musician proves to be as elusive as the humor of writing about automotive lemons.

But like Cooke's friends and associates, we are left trying to grasp a cipher. His cool what what the art historian Robert Farris Thompson calls "the mask of mind itself." We don't know how Sam felt about the white audiences he so methodically cultivated, or the women he so tirelessly took to bed; we can't measure the anger he kept hidden.

Take my advice, and beware the shape-shifting subjects of books of 750-page lengths!

Joe Queenan takes the words out of my mouth when he places Greg Critser's Generation Rx: How Prescription Drugs Are Altering American Lives, Minds, and Bodies in the category of books announcing that "the world is going to hell in a handbasket." Mr Queenan likes the book, although his ninth paragraph kicks the book off of my list.

Because of the dry nature of the subject, Generation Rx is unlikely to replace Harlan Coben as bedtime reading. Moreover, while some details may be new, the overall theme - doctors are on the drug industry tab, Republican legislators view regulation as Stalinist, consumers have developed an almost Incan belief in the power of chemicals, lobbyists run everything - is not. Still, the book is a lively well-told tale, chock-full of fascinating tidbits that will bring a smile to the face of even the gloomiest Gus.

Gloomy Guses ought to spend their time pondering regulatory schemes that Republican legislators would not find Stalinist, and not reading books that, while making one smile, intensify one's feeling of powerlessness.

I, Wabenzi: A Souvenir, has an interesting title, once it's explained. Rafi Zabor is a jazz drummer who grew up in Brooklyn. According to reviewer Liesl Schillinger, I, Wabenzi is a long meditation the author's reaction on two traumas, one involving an abortion and the other the care of his ailing parents. Although Ms Schillinger complains that "spontaneity is both Zabor's strength and his liability," she seems to like the book. "After all, he's riffing on nothing smaller than the human experience..." So I give this week's "You First" prize to Mr Zabor's memoir. If you read it and like it enough to recommend it to me, I'll read it, no questions asked.

It was a close call, that award. It might easily have gone to One Bullet Away: The Making of a Marine Officer, by Nathaniel Fick. Differing from Jarhead primarily in being the work of an officer, not an enlisted man (at least as I gather from the review), Mr Fick's book is a paean to competence, and, as such, an implicit condemnation of our way of waging war in Iraq.

Witch hunts simply doesn't interest me, which is why I'm not going to read Witchfinders: A Seventeenth-Century Tragedy, by Malcolm Gaskill. Mary Beth Norton's review fails to suggest any aspect of this new history of the Essex crusade of 1645-7, during England's Civil War, that would distinguish it from other accounts of humanity at its rock-bottom worst. Nor do I want to read about Andrew Jackson: His Life and Times, by H W Brands. I'm with William L O'Neill: "Jackson's presidency left a lot to be desired."

In "Nonfiction Chronicle," Mark Lewis rounds up six books for short-shrift treatment. Here are the titles and, in parentheses, my reason for not reading each of them, stated succinctly.

¶ Grant and Sherman: The Friendship That Won the Civil War, by Charles Bracelen Flood. (misleading title; nothing new.)

¶ The Case for Peace: How the Arab-Israeli Conflict Can Be Resolved, by Alan Dershowitz (a certain Harvard Law professor is full both of himself and of it.

¶ My American Life: From Rage to Entitlement, by Price M Cobbs (Second runner-up for "You First" award. A noted black psychiatrist "tries to cram six decades of his life into 249 pages, and they won't fit.")

¶ Radicals in Robes: Why Extreme Right-Wing Courts are Wrong for America, by Cass R Sunstein (I need to read about to find out?)

¶ The First Lady of Hollywood: A Biography of Louella Parsons, by Samantha Barbas. (Ew.)

¶ The Tulip and the Pope, by Deborah Larsen. (Third runner-up. Hey, I think I've found something. This week's most interesting sentence appears in this review: "Now a writer herself, [Larsen] recalls for us an era when life in a nunnery, for many women, was the only counterculture available.")

Three books that I'd like to read are Virginia Woolf: An Inner Life, by Julia Briggs (reviewed by Curtis Sittenfeld, who cautions that this is not a book with which to approach Woolf's life for the first time); Geoff Dyer's book about photography, The Ongoing Moment (Richard B Roundwood writes that Mr Dyer "pulls off a string of shrewd, often original ideas ... about a group of artists whose work had until now seemed thoroughly digested); and The Woman at the Washington Zoo: Writings on Politics, Family, and Fate by Marjorie Williams, edited by Williams's husband, Timothy Noah (Williams comes off as an uncommonly appealing writer).

There are two books of or about poetry this week, and this will allow me to cross from "Nonfiction" to "Fiction and Poetry." Dana Goodyear, a New Yorker editor and poet, reviews two books about poet Jane Kenyon and Kenyon's Collected Poems. One of the "about" books is The Best Day The Worst Day: Life with Jane Kenyon, by Kenyon's husband, poet Donald Hall; the other is Simply Lasting: Writers on Jane Kenyon, edited by Joyce Peseroff. The handful of examples of Kenyon's poetry are attractive, but since I'm in the middle of trying to come to grips with John Ashbery - probably by relaxing my grip - I beg to be excused. Nor can I take on Don Chiasson's Natural History, a collection of apparently feverishly hip poems. I'm not sure how to take reviewer Kay Ryan's last line, "It's the strangest thing how poetry that matters can be just an elephant's hair away from poetry that doesn't. Somebody at the Times must like Mr Chiasson, however, because his picture graces the review. Interestingly, it is a portrait; the photograph of Jane Kenyon shows her hard at work at the typewriter.

Gregory Cowles covers four novels in his "Fiction Chronicle." As is my wont, I provide the line from the review that made up my mind not to read each given title.

¶ If The Sky Falls: Stories, by Nicholas Montemarano. ("...remarkable stories are united by their dyspeptic outlook and not much else...")

¶ A Perfect Pledge, by Rabindranath Maharaj. ("In the end, the book is like a music box: it's charming and you have to admire its elaborate craftsmanship, but you know more artful versions of the song exist.")

¶ The 13½ Lives of Captain Bluebear, written and illustrated by Walter Moers, and translated by John Brownjohn. ("...further evidence ... that the Germans like their entertainment goofy and a bit bloated.")

¶ The Mercy of Thin Air, by Ronlyn Domingue. ("Readers interested in heartbreaking ghost stories from New Orleans will do well to pick up a newspaper instead.")

¶ The Elagin Affair: And Other Stories, by Ivan Punin, and translated by Graham Hattlinger. ("his writing veers between the melodramatic and the merely mellow.")

Of the four fictions given full treatment, Absolute Watchmen, by Alan Moore and illustrated by Dave Gibbons is an expensive comic book that Dave Itzoff didn't sell me on. Karoo Boy, Troy Blacklaws's apparently autobiographical account of enduring teen-aged hell in the "vast, desiccated hinterland" of South Africa known as the Karoo, thirty years ago, is making its first appearance here in paper, which means that it may well develop into a sleeper hit. Rob Nixon, however, feels that the central interracial relationship in the novel, between the hero and a retired black miner, feels "unearned" by the boy. More likely to appear on my bedside table is The Sing-Song Girls of Shanghai, a classic of Chinese literature by Han Bongqing (1856-1894) that is making its first appearance here in any kind of book, translated by the Eileen Chang, and revised and edited by Eva Hung. Sing-Song Girls is all about courtesans and their reckless, irresponsible clients. It sounds quite scrutable.

Finally, there is Witold Gombrowcz's Cosmos, translated into English by Danuta Borchardt. Reviewer Neil Gordon writes,

Praised by Sontag, Updike, Kundera, Sartre and Milosz, he is the underdog in late modernism's literary competition - perhaps, in part, because he left Poland in 1939, just before the German invasion, and remained in exile in Argentina for the next 25 years. He died in France in 1969, but since then his fiction and plays and his renowned three-volume diary have stubbornly refused to be forgotten, not only in Poland but throughout the world.

Yes, one of those guilt-inducing books that really do make you feel better for having read them, thus justifying the nagging of Sontag, Updike & Co. You first?

This week's Essay is by Jonathan Lethem. "Italo for Beginners" appears to argue for an anthology of the "best" Calvino, so that newbies will be sure to confront what the late Italian writer's dedicated admirers savor most, while regretting the interposition of editorial assistance between writer and reader. In short, Mr Lethem seems to be conducting an argument with himself in public. Unfortunately, he doesn't finish it.

To anybody who's interested in writing an opera about blogs, I propose the following rough scenario, the first act of which is drawn from fellow blogger's personal experience, as disclosed in private correspondence with yours truly. All names have been omitted.

The Bloggers Betrayed (This will sound better in Italian, as, indeed, the whole opera will, if anybody writes it. As Tom Meglioranza complained the other day, there are really only three moods in Italian music: happy, sad and angry. I think that I might add a fourth, pleading.)

Act I: Forty-something keeps racy Web log. By means of Google, the blogger's Mom discovers the blog and is shocked. Mom and Blogger swear eternal oaths, Mom never to read the blog again, and Blogger to refrain from publishing the fact that Mom knows anything about the blog.

*

Act II: Reading in Blogger's blog that she has discovered it, Mom posts a comment, furiously denying that she even knows what a blog is.

*

Act III: Mom starts up a blog, describing marital relations with Blogger's Dad, Blogger's toilet training, &c. The finale ought to be bloody, with Blogger dying of poison after having stabbed Mom.

PS: Tom Meglioranza's Tomness is NOT the source of my inspiration.

Jeannette Haien's The All of It beguilingly occupies the thinly-populated frontier between the novel and novella. At just under 150 pages, it is rather long for a novella, but its concision is characteristic of short fiction rather than long. What is essentially a short story frames the telling of a long tale. The events related in the tale occurred nearly fifty years before the present action, which in turn is confined to the space of four days. If nothing else, The All of It is a beautiful composition.

But this is not a case of "nothing else." Now almost twenty years old, The All of It looks back to the relatively unadvanced Ireland of the Thirties. We see a beautiful widow at two points in her life, her teens and her sixties. We also have a middle-aged priest, who moves from a determination to root out an old sin to the contemplation of committing a new one. Surprised by the woman's companionate charm, he is drawn to consider abandoning his celibacy, and we are left with the understanding that the widow will see to it that this does not happen.

The writing is clear-eyed and poetic, by which I mean that Ms Haien bends language to signal and provoke ineffable feelings.

Enda's house, he supposed with a sink of his heart, would be alike: dark, shut and still.

His mind tripped then on the memory of it having been but yesterday - only yesterday! - he'd driven in a retreating way up the lane in the opposite direction. But that had been after. After so much...

Continue reading about The All of It at Portico.

One of the privileges of membership at the Metropolitan Museum of Art is access to the Trustee's Dining Room. Situated over the Modern Art galleries at the rear of the museum, it is as close as Kathleen and I will ever come, probably, to eating at a club. The room is beautiful even if it is beige, and the view into the treetops around Cleopatra's Needle, with the grand buildings of Central Park West beyond, is one of the rarest in New York.

We hadn't been there at night before Saturday last. Kathleen had the bright idea of taking Dr B, one of her oldest friends in the world, to dinner there. Dr B was in town from Los Angeles to pay a visit to her parents, and we had planned for her to spend her last evening with us. But we hadn't planned anything else. I was surprised that Kathleen was able to get a table at short notice. The room, when we got there, was fairly full. Dr B loved every bit of it. Just for the record, I had a Maryland crab salad - they were out of Kumamoto oysters, which is actually a good sign late in an evening - followed by breast of guinea hen. (Oh, the sauce!) My dessert - and I was the only one to have any - was "Bananas Foster Brûlée. I suppose it was only a matter of time before someone matched the famous New Orleans treat with Manhattan's favorite.

But what prompts this entry is the reflections that were spurred by two portraits in the lobby area outside the restaurant. The museum has, of course, far more art works than it can display, and some of the overstock appear on rotation in this lobby. On one wall, there was Lawrence's John Julius Angerstein. On the other, a Portrait of a Man by Romney. The pictures are virtually contemporaneous. Yet we know the identity of only one of the sitters. The subject of the Romney picture is a blandly handsome young man with bright, clear eyes and an affable expression. It would appear that he never amounted to much. Can you think of another explanation? Lots of bright young men fail to make a mark on history. But this gent was evidently placed well enough to have his portrait done by Romney. I couldn't help thinking of Christine Lavin's wistful "Somebody's Baby," from Good Thing He Can't Read My Mind.

He once was somebody's baby

someone bounced him on her knee

do you think she has any idea

what her little boy's grown up to be.

As for John Julius Angerstein, I looked him up in Chamber's Biographical Dictionary, and found out why the name rang a bell. The entry reads,

a London underwriter of Russian origin, whose thirty-eight pictures, bought in 1824 for £57,000, formed the nucleus of the National Gallery.

That would be the National Gallery in Trafalgar Square. How'd his portrait wind up on rotation at the Met? Another line of rumination altogether.

At long last, I have embarked on a long-contemplated household project. To make room for recently-purchased CDs (where "recent" means "during the past year"), I have no choice but to "de-accession," and yet I'm loath to part with good recordings, even if I don't listen to them often. What to do?

It came to me in a vision. I would buy one of those large CD wallets - the kind that holds four to a "page." Then I would burn copies of the CDs that I planned to give away, and scan all the necessary booklet information. And, hey, it's working! I've removed one foot of jewel boxes from my shelves. And I've only just begun. The Martian-looking CD copier that has been gathering dust since last spring takes about three minutes tops to copy any CD. I wish that I could listen to the two dozen I've copied in that amount of time. So far, I've enjoyed the performances without being tempted to reconsider.

So far, each CD that I'm giving away contains duplicate recordings, which is to say that there's another performance in the collection that I prefer. Eventually, I shall have to dispose of unique recordings, but I've got more than a few, if I'm honest, that I am never going to spend any time with. But right now I'm more concerned with putting together a halfway rounded collection for Ms NOLA, who will be the first recipient of my castoffs. What she doesn't care for, I've encouraged her to give away, until the recordings find their natural homes, either with genuine music-lovers or with pack rats.

Let's hope that there are few instances of a singer gifted with a voice as beautiful as Bing Crosby's yet as prone to sing rubbish! For all of his hit recordings, Crosby sang very few songs from the American Standards canon, and most of what he did sing he alone sang. Every once in a while, thank heaven, he bumps into something that shows off his voice so well that you don't really assess the song. "Goodnight, Lovely Little Lady," from the 1934 film, We're Not Dressing.

(See right)

Like everyone else, I bought the new edition of The Elements of Style, stylishly illustrated by Maira Kalman, on the understanding that "I lost the copy that I had in school" and "needed" a new one.

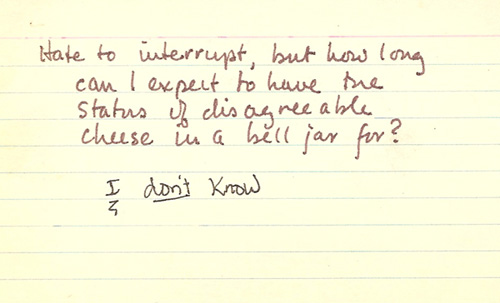

Sorry, Charlie. The old one, dating from law school days, turned up over the weekend. The only book it's bigger than is A Uniform System of Citation - a lawyer book that is, however, somewhat fatter. Tucked in the middle of Elements was the file card shown above. I proffer it as proof that I know when to stick an awkward preposition at the end of a sentence.

Neither one of us can remember what contretemps prompted this particular stay in the nuisance corner. There is no doubt that I had done something to make me smell like a bad cheese. In those days, most of my contacts with Kathleen were in public, necessitating surreptitious notes by the ream. It was a long courtship, as you can imagine.

What drives me crazy with love for my wife of twenty-four years is the squiggle under "I." You'll note that she underlined "don't," but then found that that wasn't strong enough. Ergo: squiggle. That is Kathleen.

The Sunday before last, in the course of my weekly Book Review review review, I listed the nonfiction books that I was not planning to read. The following is an item from the list.

¶ Local son Robert Long has written a book about the artists who made the Hamptons interesting as well as glamorous, De Kooning's Bicycle: Artists and Writers in the Hamptons. I would read this book, but only if asked to do so. Alice McDermott's Child of My Heart covered this territory well enough for me.

What could I say, then, when on Tuesday evening I received a note, via e-mail, from the author himself, asking me "to do so"? By Wednesday afternoon, I had the book in possession, and by Thursday evening I'd read all of it. Thank you, Mr Long, for your persistence.

I could write a few words about Jim Lewis's review (oops! I omitted his name from the item), and how it misled me to expect a very different sort of book, but I've been spending enough time on the Book Review, thank you very much. It's enough to say that I was not surprised ....

Continue reading about De Kooning's Bicycle at Portico.

A recent entry, "Free Market Fires," has elicited an illuminating comment from M François Peyrat, a Parisian who is involved in the redevlopment of the Ile-de-France, the region of which Paris is the heart but which also includes the banlieues that surround the city. M Peyrat sees the recent troubles as primarily economic, and I'm inclined to agree, although I would like to see a clearer connection between the isolation of so many maghrébins (North Africans) in what we would call housing projects, and the greater difficulty that their young men seem to have getting jobs, on the one hand, and the French economy on the other. I most heartily agree with M Peyrat that neither the US nor the UK is a "multicultural" society.

Jarhead surprised me by not being harder to take than it was. The one really painful scene came early on. Marines, still at Camp Pendleton, are watching Apocalypse Now. On the screen within the screen, Lt Col Bill Kilgore (Robert Duvall) directs an aerial attack on a coastal Vietnamese village, to a sound track of "The Ride of the Valkyries." The Marines in the theatre cannot contain their excitement; they bounce like kernels of popping corn. They're gung ho, rooting for the thoroughly undermatched American forces as if unaware that their team will ultimately lose the game. The irony of this momentary cluelessness and the tragedy of their predictable but lamentable enthusiasm for colorful carnage combine to make a bitter pill. It is a scene from Lord of the Flies, but one instigated by adults. The Marine Command must presumably be aware of the young men's inappropriate excitement. Excuse me; it's not inappropriate on the eve of engagement. Is it.

The rest of the film poses the question, Is what I'm seeing necessary? Do you have to push men this hard in order to make effective soldiers out of them? (Remember that the team of snipers featured in this drama are elite shooters, as far from Army "specialists" as you can go, at least on the ground.) It is not my place to answer, but I suggest that the price is too high. Jarhead suggests that the men killed in action - and none are, here - might be the lucky ones. Their survivors may go on drawing breath, but only at the edge of an excruciating and dismal nightmare. A nervous system stretched past maximum for months at a time will never relax to a healthy calm.

As such, Jarhead takes issue with the current manner of training and maintaining crack troops. (It's important to remember that the snipers in this drama are elite shooters, not "specialists.") The film itself is not gung ho. There is no climax to redeem the months of grueling boredom. On the contrary, there is only the anticlimax of not being allowed, ultimately - very ultimately - to take out an Iraqi target.

Jake Gyllenhaal is the star of Jarhead, but the film works best when his character, Swofford, is interacting with his partner, Troy, played by Peter Sarsgaard. While the guileless Swofford has nothing to hide, Troy is a locked trunk of secrets, and Mr Sarsgaard could have stolen the picture if director Sam Mendes hadn't resolutely featured Mr Gyllenhal. It would be silly to see anything homoerotic in the relation between the two soldiers, but it might be argued that Jarhead illumines depths of non-carnal male intimacy, which, much line sonar, functions as a series of answered challenges.

Comparisons to Three Kings, the other movie about Desert Storm, are unavoidable. What the two movies share is a complete lack of nobility. Ideals that were still available to the Greatest Generation were finished off, it would seem, in Vietnam.

What do I think about Jarhead? I don't know. But I want to see it again. Not tomorrow, but soon.

The Church of St Vincent Ferrer is a beautiful venue for evening concerts. Shadows cast by stone tracery draw the imagination into an idle play that doesn't distract from the music. But it is important to remember to bring some sort of cushion to sit on. The pews are excessively Benedictine.

Last Friday night, the Collegium presented some very familiar music in relatively unfamiliar terms. Four of Bach's six Brandenburg Concerti were played, along with ...

Continue reading about The New York Collegium at Portico.

In which we have a look at this week's New York Times Book Review.

Before I look at this week's Book Review, I want to say that the author of one of the books that I dismissed last week wrote to me to suggest that I reconsider. As it happened, I was in no position to refuse, and I'm very grateful for his persistence, as his book is a great read. I hope to discuss this further on Tuesday. For the moment, I want you all to know that I am an ardent flip-flopper when it comes to revising ignorant assessments.

Fiction first. There are four novels this week, as well as Garrison Keillor's collection, Good Poems for Hard Times, reviewed by David Orr. My own feelings about verse have gone through something of an earthquake this month, but although I'm pretty sure that I would be impatient with many of Mr Keillor's selections, I can't see any reason not to acquire this book if your library, or, as is more likely, someone else's, is bereft of poetry books. It looks like a sound beginning. Unless you're in school, and in a position to be forced to read poetry for your own good - and I often think that what Dr Johnson said about teaching Latin to small boys applies to poetry as well - then you're going to have to like what you read before you'll read more, and Good Poetry for Hard Times appears to be chock full of likeable poems. Ideally, readers will eventually tire of easy satisfactions - but only ideally.

Senator Barbara Boxer (D, California) has concocted a political novel, about a senator's successful bid to block the nomination of a conservative Supreme Court nominee, written with Mary-Rose Hayes. The Wonkette herself, Ana Marie Cox, does not think much of the result. The quoted passages are all wooden at best, and, as for politics, here's Ms Cox's closing: "Conservatives like to charge that liberals have no new ideas. Unfortunately, A Time to Run seems to prove them right. Mother's Milk, by Edward St Aubyn, is the second number in what looks to be a series of novels about an aristocratic English family on the way down. I recall that reviews of the first entry, Some Hope, characterized Mr St Aubyn as an exponent of disagreeable dyspepsia, and Charles McGrath's review gives me no reason to revise this impression.

Churlish and irritable, suffering through what he calls "this rather awkward mezzo del camin thing," Patrick is in fact just a notch or two from falling into ordinary middle-classness, and fastens on the one vestige of his family's more distinguished past - the house in Provence. Even that proves to be a fragile bulwark, however, as over the course of the novel it's slowly wrenched from its grasp.

Mr McGrath suggests that Edward St Aubyn is a successor to Anthony Powell, but I see none of the late writer's clear and decidedly not irritable grace here.

Marlon James's, debut novel, John Crow's Devil, looks interesting. Set in the author's native Jamaica in 1957, it recounts the struggle between rival preachers and their adherents. According to reviewer James Polk, it is written "with assurance and control." At the other end of experience, we have Albanian writer Ismail Kadare's The Successor (translated from the French by David Bellos). Reviewer Lorraine Adams provides a useful introduction to Mr Kadare's fiction, and notes that the author won the first Man Booker International Prize earlier this year. The Successor appears to be a historical novel of sorts about twisted relationship between the late Albanian strongman, Enver Hoxha, and his heir apparent, Mehmet Shedu.

This novel finds its truth in the imagined words of a dead man, setting the individual over the many. It valorizes the imagination by arguing that the truth of man is not always found in what he does or says but in his numinous interior, the place all great literature celebrates.

I have no plans to run out and buy any of these novels, but I'd probably try to get to them if they materialized in one of my increasingly Borgesian stacks.

Sure things: I'm going to get Sean Wilentz's The Rise of American Democracy: Jefferson to Lincoln. I didn't need Gordeon S Wood's lengthy and enthusiastic review to decide that this is a Must Read. I hope that everyone will find time for Mr Wilentz's massive tome, which, as Mr Wood suggests, might better be taken in three big doses. There is a lot for all of us to learn about just how democracy flourished in the United States in the first half of the nineteenth century - and at what cost. Another sure thing is that I'm not going to bother with Maureen Dowd's Are Men Necessary? When Sexes Collide. Ms Dowd writes pithy columns for the Times that all too often put wit ahead of substance, and I, for one, will never quite forgive her for her treatment of Bill Clinton. The Times Magazine offered us a taste of Are Men Necessary a few weeks ago. It's certainly true that millions American men have a long way to go on the way to Growing Up, but I doubt that Ms Dowd's book will inspire a single one of them to get a move on. It's possible that Maureen Dowd ought to give up on books altogether. As Kathryn Harrison points out,