Mme NOLA is in town. M NOLA was to come too - this visit to Ms

NOLA was planned ages ago - but as he was engaged in finally getting back to

work, he thought it best to remain at home. Home, at the moment, is an apartment

in the French Quarter; I believe that he is moving in this evening. There is not

much to move. The contents of chez NOLA were pretty much obliterated by

the waters of Lake Pontchartrain. Every piece of furniture save one - every

piece including the upright piano - was tipped over by the flood. The other day,

I saw photographs that were hard to believe. Flooding, yes, ruination, yes. One

grasped that. One hadn't, in advance, grasped the filth and the mold.

But Mme NOLA is here for the week, and we had to have a tour of

the museums. On her last visit, Mme NOLA and I were alone, but this time Ms NOLA got the

day off to join us. We met at the Barnes & Noble near the 86th Street stop of

the Lex. Arriving all at the same moment, we headed out again, through

sprinkling rain, to the Guggenheim, where the show, Russia!, occupies the

entire spiral. Our plan was to head to the Met for lunch afterward, and then to

see the exhibitions of medieval treasures from Prague and of "Spiritualist"

photography.

The show at the Guggenheim was a miscellany of Russian art from

the fifteenth century (or perhaps earlier) to the day before yesterday. All of

it was very competent. There were a few awkward pieces that reflected the unsure

accommodation of East and West, but these were always arresting in their

perplexity. There was a great deal of frankly derivative work - derivative of

Western styles not much in favor today outside the Dahesh Museum. There was a

very jolly bust of Catherine the Great. Among the nineteenth-century works were

several beautiful oil paintings of twilights and moonrises that I should have

called "Luminist" if only Google would support the claim; since it doesn't, I'll

say that these paintings seemed to address the same yearning as does the work of our

Hudson River School. Around 1900, things begin to get interesting in a new way;

I saw quite a few things that would be at home at the Neue Galerie (which I have

yet to revisit). Then the first bursts of native greatness: Chagall, Kandinsky,

Malevich. The show ends with a bunch of installations that demonstrate that

Muscovites are no better than New Yorkers at working out the godawful confusion

of flat-panel art and sculpture. And no worse.

My knees can handle the climb, but the descent is bruising. We

took the elevator downstairs. I thought briefly of buying the catalgue, so that

I could write more learnedly about Russia! But that seemed pretty fake. If

I go back - and I probably won't - I'll take notes. There is one really

beautiful Portrait of the Artist's Son from the early nineteenth century,

and I'm sorry that I didn't scribble down the father's name.

After lunch in the other museum, we took the magic elevator up to the Old Master

galleries. This elevator is seldom in use, but it cuts hours from getting from

the cafeteria in the basement to the Tisch Galleries on the second floor. You

pop out amid Italian Renaissance paintings, proceed through a German gallery,

and then take the Netherlandish enfilade to what I call the Lavoisier Room.

Proceeding through the Tiepolo gallery takes you to the top of the grand

staircase, where you turn toward the south - oh, I'm getting tired just thinking

about it. I marched briskly along the path just described while Ms NOLA and her

mother complimented themselves upon having someone who really knows the museum to

lead them through it - "And even if you don't know where you're going, you look

like you do."

Just how true this jest was would soon be demonstrated. For I

had no idea where we were going. I had no idea that it was there to go to.

Later, I would remember an article in the Times, and a

preview-invitation-sized envelope that I hadn't opened. But at one end of the

Lavoisier Room stood two nice ladies by a little table that read "Members Only."

I caught that first. Then,

Vincent van Gogh: The Drawings.

Well, this was a show that my guests would certainly want to see. I whipped out my

membership card and asked if it would get me in. It would get us all

in. We spent the next hour in a state of Deep Treat.

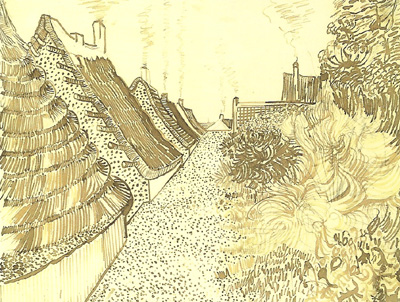

I am not a fan of van Gogh. I tried very hard, at the van Gogh

Museum in Amsterdam, to like his paintings, but they seemed increasingly

fantastic and - suitable for children's books. Their excessiveness oppressed

instead of exciting me. Since Kathleen loves van Gogh, I always feel a little

left out by this painter. But left out I shall feel no more. I will admire any

number of paintings if I can bear in mind the extraordinary works on paper that

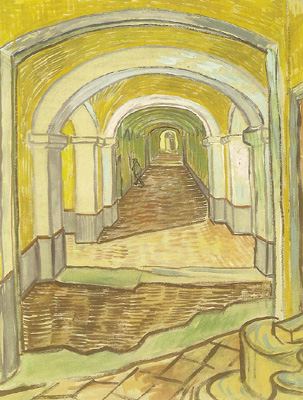

I saw the other day. From the very beginning - A Marsh (1881 ) - to the

very end - Corridor in the Asylum (1889-1890). All the extravagance of

the painter's colors reappeared to me, in the drawings, in a form much more appealing as an

extravagance of beautifully organized detail. I am still shaking a little from

having seen Rock and Ruins, Montmajour (1888). That rock!

Many of the drawings are studies for the famous paintings.

Several are "souvenirs," drawn simply to inform a correspondent of the colors of

the painting, with bleu or chrome written in between the lines of

a given area. But the most striking compare-and-contrast occurred for me when I

came upon the multimedia Harvest in Provence hanging next to its version

in oils (both works 1888). The painting, Harvest in Provence, is a star

at the van Gogh Museum, and I remember studying it hard, trying to identify what

it was that kept me from liking a picture so colorful and yet so ordered. In the

end, I came away thinking that it was too simple, and while you may

dismiss me as a barbarian, I found that the counterpart, drawn in everything

from reed pen to wax crayon, vindicated my judgment. This is the not-too-simple

version of the picture, and one has only to look at the sky to see what I'm

talking about. The painting's sky is an uninflected uniform French blue. The

drawing's sky is hardly blue at all, so busy are the cumulus clouds drifting

across it. The vitality of penned scribbles makes the profusion of brush strokes

look tired. In the drawing, we're shown what's really there, not the color of

what's really there.

This show will close at the end of the year (literally), and

then reopen in Amsterdam. It is the van Gogh show, so get yourself to it on one continent or the other. Let's hope that the

fact that there aren't many paintings on view will keep the crowds somewhat

smaller than they might be. Then again, let's not.

After van Gogh, Prague, The Crown Jewel of Bohemia,

1347-1437 seemed as miscellaneous, if more spectacular, than Russia!

I'll have to go back. As for The Perfect Medium: Photography and the Occult,

it was icky. Most of the images are tiny and tawdry. Example: Three

Phalluses. Maybe I haven't got that right. It could be The Phalluses.

It is obviously a photograph, one way or another, of three fingers. There is a

jokey sequence of shots of two men in which one makes reappearances in

transparent garments - a curious anticipation of X-rays, but more salacious. We

know what they were thinking, the photographers who produced these documents. As

for the customers, they just weren't thinking at all.

And then it was out into the rain. The rain that fell faster

and heavier the closer we got to my apartment, where we would drink tea. When I

turned my head and shoulders a bit, at one corner, to see if the ladies were

still behind me, Ms NOLA called out, "We're here," and her mother echoed, "the

ducklings are following you." It appeared from my trousers that I'd taken a

great deal of the wet that might have soaked them.

Mme NOLA has been homeless since 28 August, when she joined the

evacuation of New Orleans. On 17 October she will hang her hat under her own

roof for the first time since then. Showing me the before-and-after pictures of

her home, she joked that her husband had mowed the lawn on the 27th. It was a

lovely green lawn - Mme NOLA thought to take a picture as they drove away. It is

now a dank, brown and ugly waste. But why stop at superficial gardening. How

would you like to have this happen to your kitchen?

The minor miracle on display in this photograph is that almost

all of the photographs and other memorabilia taped and magneted to the

refrigerator door and side survived, thanks, I suppose, to really good gaskets.

Note that the waterline on the appliance is rather low; it clearly floated out

the storm. Had the water risen no higher than that watermark, a lifetime's

collection of artwork would have been spared.

All of the photographs of chez NOLA are horrifying, but

there's something obscene about the tilted refrigerator that stopped me cold. I

wanted to publish it the moment I saw it, and yet I felt that asking for

permission would be gross. That was Monday. By last night I'd hardened a bit,

and decided to ask. I was given permission at once - and I was surprised by

that. To me, this picture represents such an unforgivable invasion of personal

space that I would never want anyone else to see it - although, in my capacity

as daily blogger, I'd have run it anyway. But the tragedy has taken my very evolved

friends and evolved them a little more.