Isabel of Anachronon

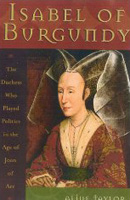

Aline S Taylor's Isabel of Burgundy: The Duchess Who Played Politics in the Age of Joan of Arc, 1397-1471 tantalizingly promises the chance to get to know an important but largely unknown woman. Why haven't we heard more about this lady, granddaughter of John of Gaunt, sister of Portugal's Prince Henry the Navigator, and wife of the most illustrious of the Dukes of Burgundy, that curious, ultimately stillborn sovereignty that buffered the borders of France and the Empire for just over a century? On the basis of Ms Taylor's biography, I'd chalk up her lack of renown to her virtue and her capability. Her virtue kept her out of the tabloids, so to speak, while her capability, while noted in its day, remains difficult to assess. On several occasions, Isabel took part in diplomatic negotiations, and she seems to have known what she was doing. As a woman, however, Isabel could be seen as nothing but an exponent of her husband's wishes. We know that she operated rather independently, and often with better sense than the vainglorious Duke. But it would have been scandalous to praise her as an independent thinker. This is the point that Helen Maurer takes such enormous pains to establish in her book about Isabel's contemporary, Margaret of Anjou.

The difference between the two books, in fact, will be a source of mild entertainment who reads both of them. Ms Maurer's interpretive tact, informed by the formulaic nature of much Fifteenth-Century chronicling, absolutely prevents her from speculating on her subject's state of mind. Ms Taylor's narrative, in sharp contrast, borders on historical fiction.

The dowager duchess Isabel also left Bruges shortly after the wedding celebrations for the quiet privacy of her estate at La Motte-au-Bois. At peace in the shade of her beloved forest, she expressed pleasure in her new daughter-in-law's progresses throughout Burgundy and was satisfied that both Margaret and Marie were comfortably situated in Brussels for the month of August. As these ladies spent their days at Coudenberg, alternately reading and hunting in the adjoining parkland forest of Soignes, Isabel was occupied with the strategies of Charles and Louis XI. She was aware that her son's larger plan to expand Burgundian territory into the empire held more promise in 1468 than when pursued by his father all the years before; the duchy now benefited from the firm English alliance she had worked so long to obtain. Isabel had no doubt that Louis XI threatened Burgundy's western frontier, and she approved of her son's military opposition to the French forces that gathered south of the Somme River. But never an advocate of battle to solve diplomatic issues, Isabel hoped for a peaceful settlement between France and Burgundy that would allow Charles to turn eastward to pursue the crown so long sought by his father.

The days when one can read this sort of thing with comfort are long over. Everything that the author attributes Isabel's state of mind in this passage is speculation pure and simple. It is probably not contrary to the truth, but the fact is that we have no way of knowing the truth. Even if Isabel had kept a diary — an unthinkable habit for the time — we would be forced to regard every entry as motivated by appearance. The plain truth is that the sphere of "quiet privacy" in which a diary might be kept had yet to be invented.

This is especially regrettable because Isabel really does appear to have had a head for facts and figures. But when we're told that "Isabel offered the [English] merchants the opportunity to do more profitable business with the Flemish looms, correctly assuming that the merchants would be more likely and more able to change the Staple regulations than the royal officers with whom she had previously negotiated," we look for a source. But none is given; indeed, the chapter in which this observation appears is one of the two out of ten chapters for which no notes are supplied.

"As Isabel embraced the Renaissance spirit of her father's court...." What an enticing proposition. How unusual such an embrace would make Isabel among the Northern European women of her day. The statement is spun sugar, however. In the first decades of the Fifteenth Century, the intellectual movement that we call the Renaissance looked to contemporaries as a simple improvement in manners, not a dramatic new movement. A sense of shift would come later in the century, but it would remain dim until well into the following one, when, shaped by the intimately related developments of the Reformation and of critical philology, a genuinely modern sensibility began to be aware of itself — as we see in Montaigne and Shakespeare. For all her patronage of humanism (or book production), Isabel was a demonstrably pious medieval aristocrat. When the citizens of Dinant insulted her honor with lewd public displays, in 1466, she demanded that her son exact vengeance, and the city was sacked.

At the end of her book, Ms Taylor writes,

The tangible evidence of Isabel of Portugal's accomplishments has all but disappeared. Most of her letters and personal documents no longer exist; all of her residences have been destroyed; her tomb has been emptied. But this diminutive princess left a clear imprint on the history of Burgundy.

"Imprint" is the very word; like a footprint, Isabel's activity can be traced as a vacancy, as the absence of events that did not happen. As Helen Maurer's book demonstrates, the account of such a negative life poses austere challenges to writer and reader alike, and not for a moment does it appear that Ms Taylor contemplated a book that would fail to present her subject as an engaging, appealing women, with many recognizable virtues and as big a soupçon of modern feminine characteristics as the solid evidence wouldn't actually prohibit. Isabel of Bavaria provides a very readable account of the interplay of major strands of Northern European history at a pivotal moment: dynastic ambitions vied with the international trade in wool for primacy in the public affairs. The account would be somewhat more lucid if Ms Taylor were not intent upon portraying Isabel as a hard-headed businesswoman as comfortable at the negotiating table as in the administration of poor relief. It is unlikely that Isabel had anything like the level-headed, "realistic" detachment that a modern reader might guilelessly infer from this fundamentally anachronistic life. She was, above all, a princess and a duchess, and it cannot have occurred to her that the merchants with whom Ms Taylor has her all but haggling would within a few centuries create a world in which her position would be strictly ornamental. (July 2008)

Copyright (c) 2008 Pourover Press