Reviewing the Book Review

Lives of the Novelists

25 July 2010

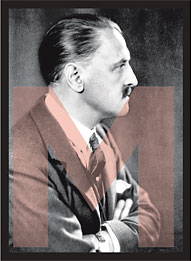

¶ David Leavitt on The Secret Lives of Somerset Maugham: A Biography, by Selina Hastings. Having characterized Ms Hastings's style as one that "privileges breeziness and readability over compassion," Mr Leavitt evinces a sour distaste for her subject.

Indeed, as I read Hastings’s biography (and I read it in great gulps), I could not help wondering if Maugham might deserve the “flaying alive” to which she subjects him. After all, here was a man who, despite his passionate erotic partnerships with two men, could write with detached humor that “the homosexual” has “small power of invention, but a wonderful gift for delightful embroidery”; a man who, in a late memoir, so vilified his deceased ex-wife as to provoke one friend, Rebecca West, to denounce him as “an obscene little toad” and another, Graham Greene, to dismiss the memoir as “a senile and scandalous work”; a man who tried to disown his own fragile daughter on the grounds that he had no evidence that he was actually her father.

I could go on. Hastings makes a strong case against Maugham the man. Where she runs into trouble is in her halfhearted attempt to make a case for Maugham the writer. Is it, in fact, “safe to say,” as she does, that Maugham “will again hold generations in thrall, that his place is assured”?

Probably not. “I know just where I stand,” she quotes him as having said on more than one occasion; “in the very front row of the second-rate.” If so much of Maugham’s fiction comes across today as brittle, arch, world-weary and heartless, it may be precisely because he devoted more energy to maintaining his own double standard than he did to interrogating the double standards of others. He tried to have it both ways, and as his stories so amply demonstrate, those who try to have it both ways rarely come to a happy end.

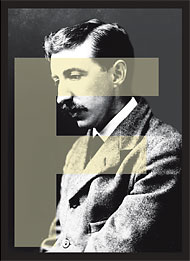

¶ Colm Tóibín on A Great Unrecorded History: A New Life of E M Forster, by Wendy Moffatt. Calling Ms Moffat's book "a well-written, intelligent and perceptive biography," Mr Tóibín proceeds to dismantle the idea that Forster's career was cramped by the inadmissibility of homosexual passion.

Forster believed that his own life as a novelist had been stunted by his inability to make fiction out of his sexual desires. This was how he explained his silence as a novelist after “A Passage to India.” While this seems to make sense, it is perhaps too easy, and perhaps even untrue. It may be more true to say that Forster wrote the five books on which his reputation rests because he desperately needed to create characters and situations that would expose his own plight in ways that were subtle and dramatic without being obvious or explicit. His true nature was not only homosexual, it was also wounded, mysterious and filled with sympathy for others, including foreigners and women. Despite his best intentions, he allowed all of himself into the five novels published in his lifetime, and only part of himself into “Maurice.”

There is a strange moment in Moffat’s book when she refers to “Maurice” as Forster’s “only truly honest novel.” But “Maurice” is, while fascinating in its own way, also his worst. Perhaps there is a connection between its badness and its “honesty,” because novels should not be honest. They are a pack of lies that are also a set of metaphors; because the lies and metaphors are chosen and offered shape and structure, they may indeed represent the self, or the play between the unconscious mind and the conscious will, but they are not forms of self-expression, or true confession.

¶ Liesl Schillinger on Father of the Rain, a novel by Lily King. This warmly enthusiastic review of a book about a dutiful daughter's misguided attempt to "rescue" her narcissistic father ought to be the making of Lily King, if making is needed.

Gardiner Amory, whatever his failings, has a permanent address. He knows how to marry and remarry, how to hold his liquor and keep up his tennis game. His daughter thinks he’s a mess, but to himself and his peers, he seems “perfect the way he is.” Some of his friends think Daley’s the one with the problem. “I wish you wouldn’t focus on your father’s flaws,” a neighbor chides. King shows the truths of their conflicting perceptions. Certainly, at 60, Gardiner doesn’t want to be reformed. “I know exactly what I want,” he blurts out at last, sick of his daughter’s interference. What he wants is for her to “butt the hell out.”

In “Father of the Rain,” King knowingly, forgivingly, shows both why Daley can’t butt out and why she must. Daley knows she’s guilty of being “bad at trusting the future,” but she can’t admit that this weakness is a crime against herself. Her father, with his unreflective gusto, and her lover, with his pragmatic idealism, have more in common than first appears: both engage with the future, however complicated, however uncertain. In their different ways, these two must steer her forward, teaching her about the duty she owes herself.

¶ Pankaj Mishra on The Subtle Body: The Story of Yoga in America, by Stefanie Syman; and The Great Oom: The Improbable Birth of Yoga in America, by Robert Love. Mr Mishra writes with engaging brio about a prominent vein in the hotbed of East-West nonsense. If he were a whit less winning, or could not see his way to finding virtues in both books, we'd blush for shame at the assignment.

It was in India that the tradition of Tantrism first exalted the human body as the source of this-worldly liberation. The generation of semi-Westernized Indians who brought about the renaissance of yoga in the early 20th century were themselves syncretists, combining ideas from both East and West. Even the physical aspects that dominate yoga today are partly reimports from the West. T. Krishnamacharya (the South Indian teacher of Indra Devi), B. K. S. Iyengar and K. Pattabhi Jois borrowed from gymnastic postures introduced to India by British colonialists.

Whether in the streets of Mysore or on Fifth Avenue, yoga cannot be disentangled from specific histories or specific cultural and economic practices. Of course, the more vulgar aspects of its inevitable commodification in the United States, like $1,000-a-night yoga cruises, ought to be deplored. Certainly, the civic or political virtue that results from limber, yoga-toned bodies is not yet measurable. And it would be nice if American followers of yoga, who increasingly define the future of this Indian discipline, would at least occasionally seek something like spiritual transcendence, though, for some at any rate, prolonged lovemaking and deeper orgasms will remain more feasible than — and may even resemble — ecstatic oneness with the big Self.

¶ Daniel Wallace on What Is Left the Daughter, a novel by Howard Norman. Having claimed that this novel has partially overcome a resistance to epistolary novel, Mr Wallace is strangely silent on the roll played by letter-writing in this novel, the strangeness of which, we suspect, is somewhat exaggerated.

His letter starts off with a bang — or, rather, a splash. Two of them, in fact. Wyatt’s mother and father, having fallen in love with the same woman, both commit suicide by jumping off separate bridges on the same night in August 1941, when Wyatt is 17. I’m tempted to quote Oscar Wilde: “To lose one parent may be regarded as a misfortune; to lose both looks like carelessness.” In this case, however, it’s not so much careless as it is amusing — more amusing than double suicides usually are, anyway. Norman, the author of “The Museum Guard” and “The Bird Artist” along with several other books, is a gentle, deliberate writer, and his humor is smart and dry, sometimes almost arid. When Wyatt pays a minister $50 for conducting his parents’ funeral, the man looks inside the envelope and shakes his head. “You know, I usually charge $50 each.” Among his mother’s last words are “I suppose this will be all over the radio”; his father jokes, “What I want on my gravestone is: I just knew this would happen!”

¶ Rebecca Barry on Termite Parade, a novel by Joshua Mohr. Intentionally or not, Ms Barry makes this novel sound like an envoi to adolescence, with all the charms and limitations of that genre.

In lesser hands, this would be another in a long line of feel-bad books examining the human underbelly, in which reprehensible characters do reprehensible things until you just want them to get over themselves and grow up. And some readers may feel this way at times — for instance, when Mired has a chance with a Buddhist vegan who’s great in bed, but then finds herself drawn yet again to Derek, who is dancing on broken glass in his own kitchen to purge the termites he imagines are eating his insides. But as Mohr demonstrated in his previous novel, “Some Things That Meant the World to Me,” he has a generous understanding of his characters, whom he describes with an intelligence and sensitivity that pulls you in.

This is no small achievement. Mired, Frank and Derek do not behave well. They drink too much. They’re irresponsible and apathetic about their jobs. Frank continues filming a mugging he witnesses in Golden Gate Park instead of helping the victim, because, as he puts it: “You wait for something your entire life and it falls into your lap and what are you supposed to do? . . . Are you supposed to limp back to your cubicle and edit another batch of training videos?”

¶ Dominique Browning on The Cookbook Collector, a novel by Allegra Goodman. This review largely compensates for its excessive storytelling by celebrating the novelist's imaginative generosity — although we do wish that rather more (or altogether less) were made of the "lichenologist" detail.

A cache of cookbooks becomes the bonding medium for Jess and George. A mysterious, ashen-faced, gray-eyed woman with long gray hair — a veritable shade — arrives at the shop one day with a request that George inspect a collection of 873 cookbooks left to her by her uncle, a lichenologist. She had promised the old man she wouldn’t sell his books, but she can’t afford to honor that agreement. They’ve been stored in his kitchen: every cabinet and shelf, even the oven, is stuffed with ancient, valuable cookbooks. Clippings, drawings and notes, held with rusting paper clips, are jammed into their pages.

George asks Jess to help him catalog and appraise the collection, but what he really wants is to cook for her, nourish her, feed her. Clearing the table after an elaborate dinner with his friends, George slips into a sensual fantasy of abundance. He imagines serving Jess succulent clementines, pears, strawberries, figs. He sees himself poaching Dover sole for her, grilling spring lamb, roasting whole chickens with lemon slices under the skin. “That would be enough for him.” To which I can only add: me too.

¶ Virginia DeJohn Anderson on Revolutionaries: A New History of the Invention of America, by Jack Rakove. Although the reviewer appears to wish her author well, her ultimately unsympathetic judgment is helpful to no one.

While acknowledging this profound failure of the founders’ imagination, Rakove invites a renewed appreciation for the undeniable accomplishments of the first of America’s “greatest generations.” Still, his conclusion is too optimistic. It derives as much from his chronological framework as from the story he tells. Ending not with the ratification of the Constitution or Washington’s election but with Hamilton’s plan for a strong and fiscally sound central government, Rakove implies that this final achievement was more durable than it in fact was. Jefferson’s election a mere eight years later would begin the process of dismantling Hamilton’s program, and Andrew Jackson would deliver the coup de grâce during the Bank War of 1832-33.

The Revolution produced other kinds of revolutionaries than those included here. Daniel Shays, the Massachusetts farmer whose antitax rebellion in 1786-87 is generally considered a major impetus behind the Constitutional Convention, scarcely rates a mention. Patrick Henry, the original Tea Partiers of 1773 and other unruly folk whom many Americans invoke today as their inspiration likewise receive little comment. The leaders Rakove portrays, however, could hardly ignore these people in constructing a government that rested upon popular consent. Indeed, the true measure of the founders’ genius may well lie in the way they grappled with the centrifugal tendencies of the Revolution to create a federal system that has lasted for more than two centuries.

¶ Howard Hampton on Rock and Roll Will Save Your Life: A Book by and for the Fanatics Among Us (With Bitchin' Soundtrack), by Steve Almond; and The Fine Wisdom and Perfect Teachings of the Kings of Rock and Roll: A Memoir, by Mark Edmundson. One of the more execrable reviews to appear in the Book Review, this sneering, competitive dismissal is a working excuse for not buying books.

Likewise wobbly in its search for meaning with a capital Mmmm, Edmundson’s “Fine Wisdom” is sweetly besotted with unlikely mentors: these are the “Kings” of the title and of the road to knowledge, bearing gifts of mojo and mind-altering substances. The Marxist arena security chief, the Zen capitalist and the headmaster who “paced the earth in big strides, as though he owned the part of it he was traversing or was seriously contemplating a down payment”: pocket Colossi who help invigorate our hero and propel him out of himself. It’s a charming if male-dominated book, a young man’s version of “An Education,” so it’s easy to picture the section on the Woodstock Country School in Vermont being adapted by that movie’s makers. But charm isn’t quite enough to get you into the palace of wisdom. Or “Beggars Banquet,” for that matter.

The funny thing about “Rock and Roll Will Save Your Life” is the way it shifts from starry hit makers of the ’80s to an aesthetic of quasi-handmade approachability — artists so far below the radar you need a magnifying glass to find them. The kind you could meet after a show and have a beer with, give them a hand with their equipment, regular people you might reach out and touch. The best, and best known, of these is Joe Henry, a quiet man who has pitched his tent in deepest left field, singing songs like “Richard Pryor Addresses a Tearful Nation” while coming at you from three or four musical/literary angles at once. If Almond were serious about his premise, he’d surely have to make a real case for why (and how) the people who are perfectly content with their Styx or Creed would want to take up someone as steeped in the elusive and unfamiliar as Henry. He’s not readily approachable as an artist, however friendly and open he may be. His music is the antithesis of what practically everybody is used to, operating within a frame of reference so variegated, nuanced and layered it might as well be folk-bop from Mars.

¶ Daniel Gilbert on Being Wrong: Adventures in the Margin of Error, by Kathryn Schulz. As this is our Hands Down Book of the Year, we cannot help faulting Mr Gilbert for missing the ethical component (admittedly understressed) of Ms Schulz tour of error.

“Being Wrong” is smart and lively, but not without its faults. Schulz promises what she calls a “wrongology” but never builds the systematic arguments that “-ology” requires. Instead we get a “wrongologue” — a series of observations and insights that leave us feeling that we’ve had all the good thoughts one could possibly have about wrongness, but that we still don’t know which ones are . . . well, right. Compelling points are not assembled into necessary conclusions, and so her book ends up being the sum of its parts, but not more.

Error, though, is a sweeping subject, and a rigorous wrongology may be too much to ask of anyone. Schulz tells us early on that her goal is “to foster an intimacy with our own fallibility” and to “linger for a while inside the normally elusive and ephemeral experience of being wrong.” These goals she accomplishes with aplomb. For most of us, errors are like cockroaches: we stomp them the moment we see them and then flush the corpse as fast as we can, never pausing to contemplate the intricate design of nature’s great survivor, never asking what it might reveal beyond itself. But Schulz is the patient naturalist who carefully examines the nasty little miracles the rest of us so eagerly discard.

¶ Leo Damrosch on Dreyfus: Politics, Emotions, and the Scandal of the Century, by Ruth Harris. It is surprising to read a review of this book that, unlike the others that we've seen, does not cover (although it does mention) two other recent titles on the subject, by Louis Begley and Frederick Brown. In fact, given the final paragraph, it's downright strange.

The story is clearly a very rich one, exposing the determination of military and political leaders to cover up their errors at all costs and, still more profoundly, the bigotry that foreshadowed the genocidal horrors of the 20th century. It was apparently at this time, too, that the word “intellectual” assumed its modern connotations, with writers and thinkers acquiring a prestige in public debate that they have retained in France to this day.

In the splendidly terse “Why the Dreyfus Affair Matters” (2009), Louis Begley brought a lawyer-novelist’s insight to untangling the deceptions through which Dreyfus was framed, and he suggests explicit parallels with post-9/11 legal abuses by the United States. More spacious, and also more densely detailed, is Frederick Brown’s “For the Soul of France: Culture Wars in the Age of Dreyfus” (2010), which traces the development of racist nationalism and reactionary Catholicism from the mid-19th century onward until they culminated in the Dreyfus Affair.

For readers who want a concise account of what Harris calls “the most famous cause célèbre in French history,” Begley’s book and Brown’s chapter will appeal. For the story in depth they should turn to Harris’s excellent “Dreyfus,” which deserves a wide audience for its patient, fair-minded exploration of human ideals, delusions, prejudices, hatreds and follies.

¶ Mark Atwood Lawrence on Through the History of the Cold War: The Correspondence of George F Kennan and John Lukacs, edited by John Lukacs. Although Mr Lawrence refers (without, however, naming it) to Mr Lukacs's 2007 biography of his friend and correspondent, the review would have done better to treat the letters in view of the portrait.

The collection conveys their enormous erudition and (especially on Kennan’s side) stylistic brilliance. More than anything, though, the book poses anew, in an admirably lean and accessible way, a question that has long swirled around Kennan: What were the intellectual underpinnings of his insistence on a restrained, “realist” foreign policy that shunned bold efforts to remake the world in the American image?

One answer is surely Kennan’s inordinately pessimistic assessment of human capabilities to effect change on a grand scale. If the world managed to escape catastrophic war, he wrote in one characteristically dark letter in 1953, “it will not be because of ourselves but despite of ourselves: by virtue, that is, of the fact that we have so little, rather than so much, control over the course of events.” Mere randomness was, for Kennan, a better bet for a happy outcome than the conscious efforts of well-intentioned people. Even they, after all, were constrained by “man’s fallen state.”

But Kennan’s ideas about the United States’ role in the world also sprang from his particular disdain for American democracy. An unashamed elitist ill at ease with his own modest upbringing in Milwaukee, he viewed Americans as dangerously susceptible to the pedestrian tastes of the majority, unmoored as they were from the aristocratic sensibilities that Kennan considered the best hope for resisting mindless enthusiasms.

¶ Richard Lourie on The Eitingons: A Twentieth-Century Story, by Mary-Kay Wilmers. The review starts off on an unhelpful insidery note, and never recovers.

English on her father’s side, Mary-Kay Wilmers, the editor of The London Review of Books, is related on her Russian mother’s side to the dangerous and flamboyant Eitingons. In this chatty and often engaging group biography, she portrays three of them: Max (1881-1943), a psychiatrist and member of Freud’s inner circle; Motty (1885-1956), furrier extraordinaire, who continued an already successful family business (“We never talked about money,” one relative remarked, “because we had so much of it”); and Leonid (1899-1981), a dashing assassin for the Soviet secret police (“I hold my life no more precious,” he explained, “than the secrets the state has entrusted me with”).

Permalink | Portico | About this feature

Copyright (c) 2010 Pourover Press