Reviewing the Book Review

Do I Contradict Myself?

20 June 2010

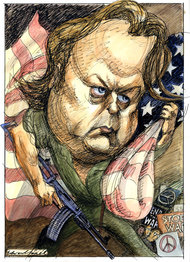

¶ Jennifer Senior on Hitch-22: A Memoir, by Christopher Hitchens. The reviewer is nicely sympathetic to the author's limitations qua memoirist.

None of this means that “Hitch-22” isn’t marvelous in its own way. But it’s probably a misnomer to call it a memoir, and easier to enjoy if one thinks of it as a collection of essays instead. Our protagonist is a bit of a disembodied brain, highly capable of poignancy but not exactly introspection or, as is welcome in memoirs, overwhelming indiscretion. (Would it be primitive to say that he seems so English in this way, though he’s become an American citizen?) When he shares a tender memory, his preference is to quickly convert it into a larger political observation; for him, politics remains the most crucial sphere of moral and intellectual life. At the beginning, for instance, he draws a compact, empathetic picture of his mother, who struggled to make a glamorous life for herself in the British naval towns where his father was based, and who would one day run off to Athens with a lover and take her life in a suicide pact. (I was particularly moved by his story about her one attempt to take a solo road trip, only to return the next day with her neck in a brace, “having been painfully rear-ended by some idiot before she had even properly embarked on the treat that was rightfully hers.”) Yet only a few pages later, when he recounts his efforts to arrange her burial in Greece, he freely acknowledges his trip was as political as it was personal. He recognizes that the coroner in his mother’s case was a famous villain in the military junta’s machine; he makes reporting side-trips to talk to student protesters; at the cemetery where he lays his mother to rest, he stops to pile carnations on the grave of George Seferis, the poet and national hero.

¶ Philip Caputo on Girl By the Road at Night: A Novel of Vietnam, by David Rabe. Mr Caputo obliges us to take his claims for this book on faith

Whitaker meets Lan by chance and becomes one of her customers until something happens between them. It’s less than love, but a great deal more than commercial sex. And that tenuous bond opens Whitaker’s mind and heart to new possibilities, even the idea that he’s capable of overcoming his own crippled nature: “Maybe now in the desolation of this . . . country, amid these poor miserable empty people, he will be able to find himself, he thinks, somehow locating the lost part of himself that he knows is in there.” He is moved, finally, into a brave and decent act, rescuing Lan from two menacing Vietnamese soldiers.

A scene like that, indeed the whole book, would be hopelessly shopworn in less capable hands, “Miss Saigon” in prose. Rabe pulls it off, as he does his depiction of Lan, without a whiff of sentimentality. The dialogue is what you’d expect from a skilled dramatist, so true you feel you’re in a room with the characters. The pidgin English in which Lan and Whitaker communicate at times sounds like a weird poetry.

It would have been precisely helpful to quote a patch of that "weird poetry."

¶ Robert Sullivan on The Lost Cyclist: The Epic Tale of an American Adventurer and His Mysterious Disappearance, by David Herlihy. This guardedly sympathetic review suggests that the author missed the humanist point of his own story.

At the buried moral center of “The Lost Cyclist” is Sachtleben. He knew that Outing’s offer to undertake the rescue would “renew his reputation as a world wanderer and roving reporter par excellence,” and that he “might even delve into the Armenian massacres and make himself an even more valuable commodity on the lecture circuit.” After he witnesses another killing, Outing withdraws its backing. But Sachtleben won’t budge and eventually pushes for charges against Lenz’s killers. Herlihy, however, seems annoyed by Sachtleben’s muddled attempts to exonerate some Armenians who had been falsely accused, suggesting he should have “concentrated on finding Lenz’s grave rather than on meting out justice in Turkey.”

The implication of this paragraph is that The Lost Cyclist does not belong in the Book Review.

¶ Christ Suellentrop on Extra Lives: Why Video Games Matter, by Tom Bissell. Mr Suellentrop appears to believe that this book offers a lucid explanation of a divisive pastime; perhaps it is the reviewer who's doing that.

If photographs are “experience captured,” in Susan Sontag’s phrase, then video games are experience created. The medium can be so engaging, so addictive — Bissell compares playing games to his time using cocaine — that many game makers get away with fiction that makes Stephenie Meyer “look like Ibsen.” A novel or a movie that is poorly written is relatively easy to abandon. Well-designed games that feature bad writing “do not have this problem,” Bissell notes. “Or rather, their problem is not having this problem.”

Roger Ebert and those who agree with him are unlikely to have their minds changed by a book. You can understand video games as a medium of communication, or as an emerging art form, only by playing them.

¶ Maggie Scarf on A Fierce Radiance, a novel by Lauren Belfer. The too-short-seeming review of this "death-haunted medical thriller" is almost suspiciously warm, as if Ms Scarf had decided not to end the following paragraph by noting that, having run its course, the adventure leaves no traces.

Belfer’s first novel, “City of Light,” delineated the social and political tensions of Buffalo, N.Y., at the beginning of the age of electricity. “A Fierce Radiance” is similarly ambitious, combining medical and military history with commercial rivalry, espionage and thwarted love. Belfer clearly knows her scientific material. She also knows how to turn esoteric information into an adventure story, and how to tell that story very well.

¶ Roy Blount on Globish: How the English Language Became the World's Language, by Robert McCrum. This not the first unsympathetic review that Globish has inspired. One almost wonders if it might have been better written in Globish itself and marketed to people for whom English is a second language at best.

McCrum, in fact, provides evidence that the globalizing of English will water it down, at least literarily:

“Such is the obsession with the transforming power of the marketplace in the new China that the eager young booksellers I spoke to were concerned to know more about likely British ‘best sellers.’ The idea of a little book making its way through word of mouth and the quiet accumulation of devoted readers is foreign to this generation of English-language readers. Best-seller readers in China are Globish readers. They are being willingly coerced by the soft power of a global force, and by Globish prose, a universally accessible style and story.”

Given recent number-crunching tendencies in American publishing, good books are probably already being rejected as insufficiently Globish.

¶ Liesl Schillinger on One Day, a novel by David Nicholls. Somewhat uncharactertistically, Ms Schillinger indulges in a great deal of storytelling, and brackets her full-page review with an evocation of summer's carefree reading venues. Then there's this, at the end.

Will Dex and Emma get together before it’s too late? Will they ever act on the lone un-self-conscious thought Emma has been able to hold in her head since the day she walked away from Dexter, when she was 22 and he was 23, as his parents drove him home from college into his still unblemished future? “Love and be loved,” she had told herself, “if you ever get the chance.” It’s something you may want to find out this summer at poolside. And if you do, you may want to take care where you lay this book down. You may not be the only one who wants in on the answers.

Again, it's suspicious.

¶ Andy Martin on Sweetness and Blood: How Surfing Spread From Hawaii and California to the Rest of the World, With Some Unexpected Results, by Michael Scott Moore. Our gimlet-eyed reading of this review, inclined to find the book wanting in the substance that merits Book Review coverage, we were brought up short — to the very verge of apoplexy — by the following.

I’m not sure there is such a thing as surf literature. But if there is, it has moved well beyond the self-mockery of Mark Twain (“None but the natives ever master the art of surf-bathing thoroughly”), the hyperbole of Jack London and the snazzy pop-anthropology of Tom Wolfe. Later this year, the surf writer Matt Warshaw is bringing out what promises to become the standard “History of Surfing.” Moore’s own history is a thing of shreds and patches, casually, almost randomly, assembled. But what he has done, subtly and beguilingly, is write a book about surfing that often is not really about surfing but about simply being alive (and, in some cases, dead).

¶ Mark Mazower on Russia Against Napoleon: The True Story of the Campaigns of "War and Peace," by Dominic Lieven. This warmly favorable review suggests that the author's undertaking to correct Tolstoy's may be as interesting as Tolstoy himself.

Lieven takes us into the heart of the Russian military. Himself the descendant of imperial officers, he offers us something close to a rose-tinted picture of that caste, and a notably heroic picture of Alexander himself, the man who “more than any other individual,” he tells us, “was responsible for Napoleon’s overthrow.” Lieven’s pride is evident when he reminds us that the czar’s Guards were “the finest-looking troops in Europe.”

But this pious act of memory brings with it a deep understanding of the men and the system that made the Russian imperial army so effective. There is a certain amount of Tolstoyan partying and drinking, courtly intrigue and battlefield maneuvering here, but there is also much more serious attention to the Russian ability to appraise the finely balanced strategic alternatives that loomed up almost every minute from the time the decision was taken to prepare for invasion.

Permalink | Portico | About this feature

Copyright (c) 2010 Pourover Press