Reviewing the Book Review

Capitalist With a $

1 November 2009

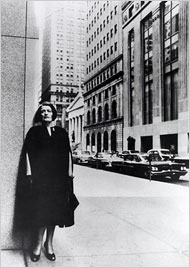

¶ In what amounts to a brief essay on Ayn Rand, Adam Kirsch pauses long enough deliver a helpful judgment of Anna Heller's Ayn Rand and the World She Made, which he also calls "dramatic and very timely."

Heller maintains an appropriately critical perspective on her subject — she writes that she is “a strong admirer, albeit one with many questions and reservations” — while allowing the reader to understand the power of Rand’s conviction and her odd charisma.

Mr Kirsch also ventures a persuasive explanation of the popularity of the ham-fisted Rand's fictions:

Rand’s particular intellectual contribution, the thing that makes her so popular and so American, is the way she managed to mass market elitism — to convince so many people, especially young people, that they could be geniuses without being in any concrete way distinguished. Or, rather, that they could distinguish themselves by the ardor of their commitment to Rand’s teaching. The very form of her novels makes the same point: they are as cartoonish and sexed-up as any best seller, yet they are constantly suggesting that the reader who appreciates them is one of the elect.

¶ Maureen Howard's warmly favorable review of Orhan Pamuk's new novel, The Museum of Innocence (translated by Maureen Freely), is appropriately nonchalant about the writer's idiosyncrasies.

There’s not much plot to “The Museum of Innocence”; and why should there be, if the artist is free? Still, Pamuk comes up with a cinematic ending, easy and swift as though churned out in a Turkish B-movie. But if, as Kemal recommends early in the novel, I turn to “Happiness,” the last chapter, I discover there how he sought out “the esteemed Orhan Pamuk, who has narrated the story in my name, and with my approval.” No trick, this is the writer’s claim to his workroom, where the gallery of his dreams displays not ephemera devoted to delusion but close attention to the “beauty of ordinary life” that has almost eluded Kemal. What’s on show in this museum is the responsibility to write free and modern. The real writer is never wholly innocent of searching out a word that, as Joseph Conrad put it in “Under Western Eyes,” “if not truth itself, may perchance hold truth enough to help the moral discovery which should be the object of every tale.”

¶ Dave Eggers sings the strengths of Kurt Vonneguts early, unpublished stories, now collected in Look at the Birdie.

more than any of his contemporaries of similar stature, Vonnegut was until early middle age a practical and adaptable writer, a guy who knew how to survive on his fiction. In the era of the “slicks” — weekly and monthly magazines that would pay decently for fiction — a writer had to have a feel for what would sell. The 14 stories in “Look at the Birdie,” none of them afraid to entertain, dabble in whodunnitry, science fiction and commanding fables of good versus evil. Why these stories went unpublished is hard to answer. They’re polished, they’re relentlessly fun to read, and every last one of them comes to a neat and satisfying end. For transmittal of moral instruction, they are incredibly efficient delivery devices.

¶ Christopher Benfy's very favorable review of Hilary Mantel's Wolf Hall would be far more helpful if it addressed the novel's quality as an historical novel more fully than by simply making the following assertion:

In her long novel of the French Revolution, “A Place of Greater Safety,” Mantel also wrote about the damage done by utopian fixers. And surely the current uproar over state-sponsored torture had its effect on both the writing and the imagining of “Wolf Hall.” Yet, although Mantel adopts none of the archaic fustian of so many historical novels — the capital letters, the antique turns of phrase — her book feels firmly fixed in the 16th century.

¶ The only word for Maria Russo's storytelling-laden review of Tobias Hill's The Hidden is "dithering." She likes some things about the novel but dislikes others, and winds up sounding like a hostess who can't decide whether to recommend a particular hors d'oeuvre.

¶ David Drzal makes appetizing work of summarizing the contents of William Grimes's Appetite City: A Culinary History of New York.

New York took decades to recover. Craig Claiborne (whom Grimes credits with single-handedly inventing serious food journalism) went so far as to call New York in the late 1950s “a hick town.” In his autobiography, Claiborne writes: “Prohibition and the Depression had dismantled the glorious edifice of dining erected at the turn of the century. The Second World War had completed the process.” Then came Joseph Baum. Part showman, part visionary, he enlivened the city’s restaurant scene with over-the-top creations like the Forum of the Twelve Caesars, which Grimes calls “an amusement park for the senses,” and more serious offerings like the Four Seasons. Baum invented the open kitchen for La Fonda del Sol and helped restore the city’s self-image with Windows on the World. “It would be an exaggeration,” Grimes argues, “but not a great one, to say that everything after Joe Baum has been a series of footnotes to his groundbreaking ideas.”

¶ Kati Marton's Enemies of the People: My Family's Journey to America gets a glowing review from Alan Furst.

If Marton was able to retrieve a sweet memory of her past, she was also to discover details, intimate details, of her parents’ lives that she might well have preferred not to know. “A Pandora’s box,” the foremost historian of the AVO correctly called the Marton files. But, in the end, Enemies of the People becomes a treatise on human nature — at its best, at its worst — and Marton is enough of a good journalist, and a good human being, to take that for what it is: applaud the love and the heroism, deplore the cowardice and the cruelty, and go on with life. She doesn’t dwell on her feelings, but it could not have been easy for her to undertake this project. Yet, as the narrative draws to a close, she understands that the twists and turns of Europe’s brutal history can sometimes, with luck and courage, end well. And turn out to be, at least for Marton, and certainly for the reader, an honestly inspiring story.

¶ Paul Barrett stops short of dismissing Duff McDonald's Last Man Standing: The Ascent of Jamie Dimon and JPMorgan Chase as a piece of publicity puffery, but just barely.

JPMorgan under Dimon’s leadership allowed home buyers to borrow without having to prove their income. The bank did business with sleazy mortgage brokers who would lend to anyone with a heartbeat. These habits ended only in 2008, when it was too late. McDonald lauds Dimon for cleverly unloading huge volumes of the toxic subprime mortgages JPMorgan originated. But that’s like praising a corporate polluter for trucking his poisonous sludge into the next state. It doesn’t solve the problem; it merely moves it elsewhere.

¶ Reviewing two new books about John Maynard Keynes — Keynes: The Rise, Fall, and Return of the 20th Century's Most Influential Economist, by Peter Clark; and Keynes: The Return of the Master, by Robert Skidelsky — Justin Fox complains that both are (for him) very slow starters.

Clarke’s book is an attempt to give readers the full Keynes, in brief. In its early chapters it founders on the reality that Keynes’s life was just too interesting, and too closely intertwined with that of other major figures of his age, to submit to a mere sketch. Unless you already know a good deal about Keynes and early-20th-century Britain, it’s just plain hard to get through. (There’s a reason that even the abridged paperback version of Skidelsky’s Keynes biography runs to 1,056 pages.) Skidelsky’s new book doesn’t attempt much in the way of biography, but it struggles for several chapters through a clunky, sloppy account of the current financial crisis and of the development of economics since Keynes.

It is only when they get to Keynes’s ideas that the books take off.

¶ Tony Horwitz concludes that Timothy Egan's attempt, in The Big Burn: Teddy Roosevelt and the Fire That Saved America, to meld the founding of the US Forest Service and the story of a rampaging forest fire in 1910 yields a forced an unconvincing result, "like a railroad where the gauges don’t match." In another negative conclusion, he disapproves of Mr Egan's colorful prose.

The prose adds to this disconnect. Egan’s research is deep, and his details are vivid: a pocket watch stopping at the wearer’s time of death, a woman burying her sewing machine to save it from fire, elk and bears fleeing the forest ahead of the flames. But rather than trust this material, Egan cranks up the temperature, charging through adjectives and clichés. Wind-driven fire is “a peek beyond the gates of hell,” while a weary ranger is “going on adrenaline, a kid trying to keep a tsunami of wildfire at bay, trying to save at least one town.”

Such pre-emption of the reader's judgment is not helpful.

¶ James McPherson, a distinguished historian of the period, is almost scandalized by the facts that John Keegan gets wrong in The American Civil War: A Military History.

The analytical value of Keegan’s geostrategic framework is marred by numerous errors that will leave readers confused and misinformed. I note this with regret, for I have learned a great deal from Keegan’s writings. But he is not at top form in this book. Rivers are one of the most important geostrategic features he discusses.

Mr McPherson's ensuing catalogue of errors is a scandal: surely a first reader at Knopf ought to have caught the English historian's blunders.

¶ Having read Terrence Rafferty's review of Peter Ackroyd's The Casebook of Victor Frankenstein, I must confess that I haven't a clue as to what kind of book is under discussion.

The Casebook of Victor Frankenstein is an entertaining and bracingly intelligent yarn, but, try as he will, Ackroyd is hard pressed to spark an idea that isn’t already burning, fiercely, in Mary Shelley’s still-vital novel. This, perhaps, is the postmodern Prometheus: an attempt, aware of its own futility, to reanimate something that never died.

Permalink | Portico | About this feature

Copyright (c) 2009 Pourover Press