Reviewing the Book Review

Appraising Grace

25 January 2009

In which we have a look at this week's New York Times Book Review.

FACT

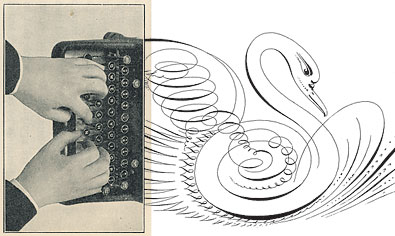

¶ Toni Bentley's review of Ballet's Magic Kingdom: Selected Writings on Dance in Russia, 1911-1925, edited and translated by Stanley J Rabinowitz, a newly-translated collections of the writings of Akim Volynsky is a model that the editors of the Book Review ought to tuck into each book that they assign. Informed, enthusiastic, and decorously aware of ballet's strong erotic undertow, the piece will kindle an interest in readers with no prior interest in classical dance.

Aside from priceless portraits of dancers, Volynsky devotes himself to the language of ballet and its meanings. If you’ve never been quite sure what an arabesque really is, Volynsky explains: “The leg thrown back into an arabesque is, of course, nothing but a symbol of consciousness in its forward rush.” In fouettés, he writes, “the soul becomes the arena of the most intense feelings, from healthy and natural to pathological and demonic.” (“Swan Lake” requires 32 of these demonic interludes in quick succession, resulting, historically, in more than a few pathological ballerinas.)

¶ Although Jennifer Schuessler makes many interesting remarks in her review of Dalton Conley's Elsewhere USA, I was unable to determine what kind of a book this is. At times, Ms Schuessler makes it sound more like a memoir than a reportage. The conclusion rings too many bells for my poor brain.

Refreshingly, Conley doesn’t tell us to smash our BlackBerrys, shred the takeout sushi menu and get back to the family dinner table. “Do not hold yourself to a mythologized standard of the past,” he writes in his conclusion, before falling prey to the same confirmation bias he mocked earlier in the book, when he chided social science research for “magically” confirming that middle-class child-rearing practices are best. “The successful professional parents,” he boldly predicts, “will be the ones who manage to blend their child-rearing duties with their professional ones, making their children comfortable in high-pressure, high-status work environments.” Follow the citation to some intriguing research conducted in the Conley home (n)office. “Here I must confess to years of screaming at my wife for trying to involve the kids in her work life as well as yelling at her to turn off her cellphone during ‘family time.’ I was wrong, and she was right. . . . But I can’t bring myself to apologize in the main text, so I am relegating this to an endnote.”

There's an air of hysteria in this paragraph that makes me doubt that anybody, much less children, can be "comfortable in high-pressure, high-status work environments."

¶ Astonishingly, Timothy Egan's review of Fifty Miles From Tomorrow: A Memoir of Alaska and the Real People, by William L Iggiagruk Hensley, neglects to state the year in which the author was born, depriving the reader of a sense of context. The editors have taken a stab at a fix, subtitling the review, "A man's life and a state's, beginning in the 1940s," but it turns out that the omission is symptomatic of the reviewer's preference for the quickly picturesque.

Hensley was raised just north of the Arctic Circle on the shores of Kotzebue Sound. On a clear day, he probably could see Russia from his house, for it’s a mere 90 miles across the Bering Strait. The international date line is 50 miles away, and hence the title.

"Slush" is too nice a word....

¶ Mimi Swartz fully appreciates Brian Burrough's The Big Rich: The Rise and Fall of the Greatest Texas Oil Fortunes, a portrait of the four great oil barons of mid-century Texas. Her only complaint concerns the pile-up of factual updates at the end.

By the time we get to the successes and failures of the next generation — Clint Jr.’s excesses with drugs and women; Bunker and Herbert Hunt’s illegal-wiretapping and silver-cornering fiascoes; the takeover of Disney by the Bass brothers (Richardson’s great-nephews) — the book starts to feel more like a marathon than a jaunt. By the end I was longing to sit on one of Murchison’s verandas, drink in hand, and savor a single good story while a cool breeze blew through the trees. Murchison might have said the author bit off a little more than he could chew. Of course, that puts Burrough in some very good company.

¶ Vanessa Grigoriadis is a contributing editor at several top magazines, but does that qualify her to review Norah Vincent's Voluntary Madness: My Year Lost and Found in the Loony Bin? Although she must be more than capable of appraising its literary qualities, but she appears to be too shocked, almost scandalized by the willfulness of Ms Vincent's new reportorial project.

[Her fellow inmates] must break the cycle of mental illness, she decides; they must stop taking their medication. Does this patient know about the side effects of Effexor? Does this other one, a grade school teacher in the urban education system, really need Seroquel? Vincent tells her to palm it. “You don’t need medication,” she says. “You need to change your job.” Perhaps she’s right. But striding around a public psych ward with such pronouncements goes too far, particularly when Vincent herself is about to get knocked on her rear by her decision to taper off Prozac — partly over her frustration at being in lifetime thrall to the drug companies, and partly for the good of the book, because she thinks it’s the right thing to do as an immersion journalist. “I thought I was on my game,” she writes. “And then there I was thinking about where I could buy a gun. A gun seems best. I am a maimed animal. Perhaps I can hire a hit man. I will tip him very well to take a clean shot.”

Madness is not, ultimately, a form of entertainment. Surely someone at Peter Kramer's level would have written a more authoritative evaluation of this cheeky text.

¶ The brevity of Amy Finnerty's review of Baz Dreisinger's Near Black: White-to-Black Passing in American Culture — extreme brevity, considering the subject — suggests that the editors do not really take this title very seriously.

Black-as-white passing was a transparently explicable, if depressing, phenomenon. White-as-black passing, however, appears to have happened for a multitude of reasons a frequent one being a cultural election by the passer, for the sake of personal happiness, profit or, sometimes, a lark. The unique, eccentric stories the author has assembled are more enlightening, in the end, than her diligent efforts to connect them to one another.

¶ Steven Johnson's The Invention of Air: A Story of Science, Faith, Revolution and the Birth of America is a book about one of the co-discoverers of oxygen, Joseph Priestley. Russell Shorto praises its "post-categorical" reach.

One reason Johnson seems to have been drawn to Priestley is because of his style; Priestley was irrepressibly open, sharing his data and observations with whoever was willing to listen. This may have cost him some credit in discoveries, but to Johnson it makes Priestley the godfather of the open-source era. And this may be where Johnson’s genres blend together most fully. As a “compulsive sharer,” Joseph Priestley believed wholeheartedly in the free flow of information: in letting insights from science flow into the streams of faith and politics, in trusting in the human mind as the ultimate homeostatic system, able eventually to find its internal balance no matter how large the disruption. In his day, the French and American Revolutions were the major tests to that theory. We in our age have our own.

¶ Martin Walker's review of Jonathan Brent's Inside the Stalin Archives: Discovering the New Russia means to be favorable, but it is so reluctant to describe Mr Brent's book (as opposed to its contents, from which it snatches intriguing nuggets) that only those with a pre-existing interest in the bad old Soviet days are likely to be persuaded to read it — by Mr Walker, that is. The concluding paragraphs about Aleksandr Yakovlev suggest hidden agendas.

¶ The British lawyer Anthony Julius gives Adam Kirsch's Benjamin Disraeli a lucid and commending review that is somewhat preoccupied — as perhaps Mr Kirsch's book is as well — with Disraeli's Jewish background and his interest in Jewish affairs. It does not, at any rate, sound like a counterpart to the late Roy Jenkins's engrossing biography of William Gladstone.

Kirsch argues that the alternative career of Jewish leader was ever before Disraeli but that he did not want it. Though what Kirsch describes as “the dream” of Zionism had a “powerful allure” for Disraeli, “neither the conditions of Jewish life in Europe nor his own personality allowed Disraeli to play the role that would eventually fall to Theodor Herzl.” He imagined Judaism in ways that were psychologically empowering, but paid little attention to the condition of actually existing Jewry.

FICTION

Glen Damian's A Day and a Night and a Day gets a generally favorable and decidedly sympathetic review from Lee Siegel.

Although it’s a novel of ideas, A Day and a Night and a Day also recalls the surreal compressions of a writer like John Hawkes. As a result, Duncan’s breathtaking intellectual leaps and bounds are often lost under layers of literary writing. He’s so consumed by his language that he never bothers fully to explore Rose’s decision to throw in his lot with a gang of cold-blooded killers. The novel’s near-fatal flaw is that Rose’s bizarre moral choices and his situation as a victim of torture appear to be taken for granted, so eager is Duncan to use such conceits to examine Rose’s nature as your everyday Western man.

¶ It is clear from Maria Russo's favorable review that Ali Smith's The First Person and Other Stories is a work of brittle sophistication, and yet this is precisely the aspect of the collection that Ms Russo seems inclined to take for granted, as though other kinds of books were of no interest. The resulting airless review does Ms Smith a disservice.

¶ There's a lot of good old-fashioned storytelling in Anthony Doerr's favorable review of Water Dogs, Lewis Robinson's first novel, set in wintry Maine; but Mr Doerr goes about his summarizing with such attentiveness to the book's atmosphere that readers will be hooked by its suggestion of good old-fashioned mystery. Mr Doerr doesn't tell; he shows.

Perhaps Water Dogs feels honest in its insularity because it’s wrapped so thickly in snow. Robinson clearly understands how to make a smudge of light glow against a dark background, how to negotiate winter’s tandem essences of threat and beauty. In its rendering of the complicated, rich, mostly unspoken relationship between a young man and the place he lives, “Water Dogs” is a lovely novel. Robinson may not evoke the snow falling faintly through the universe, but he certainly evokes it as it falls over Maine.

¶ Roy Hoffman's review of Inman Majors' satirical novel about the 1982 Knoxville World's Fair, The Millionaires: A Novel of the New South, is too crammed within its short space that it has a glazed, uninformative feel.

In contrast to Majors’s fluid second novel, Wonderdog, with its bummed out but talkative narrator, The Millionaires moves like a light opera with a big cast, staged by a director who seems periodically uncertain about how to get all these characters on and off the stage.

¶ And in the same brief allotment, Nancy Kline has to make a case for the French writer Annie Ernaux's unusual oeuvre (very short books), criticize Anna Moschovakis's translation of Ms Ernaux's latest title to appear here, The Possession, and recommend other works for first-time readers. It's too much for too few column-inches.

Permalink | Portico | About this feature

Copyright (c) 2009 Pourover Press