Click above to visit the entire site

Friday Fronts

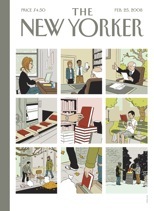

22 February 2008:

Larissa MacFarquhar on Louis Auchincloss, in The New Yorker.

Well, it would be the only thing in the magazine that's not online. It's not a terribly timely piece, either — unless the idea is to be sure to get it into print before its subject, Louis Auchincloss, is no longer alive to read it. Mr Auchincloss, who turned ninety last September, has published over sixty-four books in the past sixty-one years. Reading Larissa MacFarquhuar's profile (Life and Letters, actually) in the current issue of The New Yorker, I wonder if the man wouldn't have been luckier if he hadn't been born sixty-one years ago. In that case — if I may propose the modest example of me — he might have kept a blog. It seems unlikely, for any number of reasons, that he or anyone of his age and background would keep a blog. What a loss, though. His wit is deadly.

And usually deadpan as well. As I've watched very little television in my adult life, I've no right to the great good luck of having seen Dick Cavett's utterly wince-making (and totally unsuccessful) attempt to get Mr Auchincloss to play the tattletale with regard to his cousin by marriage, Jacqueline Bouvier &c. Our Louis responded to the interviewer's prying, brown-edged questions with the rugged taciturnity of a noble Roman undergoing deposition by an overdeodorized attorney from the plebs. "She goes to work every morning and she works very hard" — and that was all that the novelist had to say about the former First Lady's publishing career at Viking.

If he is never guilty of the capital offense of laughing at one's own jokes, Mr Auchincloss is not just being modest. "This is a test." Without the laughter, or so much as a smile, as a cue, the attorney pitilessly obliges his interlocutor to detect the occasion of levity that his demeanor firmly discourages. One shudders to think what the general sense of humor must have been like at the Groton School, when he arrived, at the age of twelve, in 1929. One shudders, tout court, to imagine an America whose sense of humor was as yet unleavened by the pretension-poking joys of Yiddish.

A world in which a story like Edith Wharton's "Xingu" is about as funny as literature gets. Which is actually pretty funny, if you can live without the sound of laughing-out-loud. Mr Auchincloss, as I say, can be very funny.

In an effort to become a proper writer, he decided that he ought to meet other writers and go to parties with them, so he fell in for a while with a group that met at the White Horse Tavern, on Hudson Street, in the Village. "A fellow named Bourjaily and his wife had a literary salon downtown, although they themselves were hardly highbrow," Gore Vidal says of this group. "But no one was literary then, except me and Louis." Vidal and Auchincloss, cousins by marriage [...], met during this time and immediately took to one another. Auchincloss, in Vidal's view, was practically the only writer who wasn't a pretentious idiot trying to be Hemingway. Auchincloss also met Norman Mailer and Herman Wouk at the White Horse Tavern, and he dutifully stayed up late and drank with them. (Years later, Mailer wondered that they should be so cordial, since they had nothing in common. "Nothing in common!" Auchincloss replied, as he described the encounter in a letter. "We live in the same silly island, publish our wet dreams, and go to the same silly parties — and have for years! It would take a mother's eye to tell the difference between us. Of course, it's true that I don't marry quite so much."

We shall draw a veil over what the two mothers might have had to talk about. We'd probably be surprised.

The world that Louis Auchincloss has written about for six decades is unknown to most Americans, and nowhere near so influential as it used to be. His day job, as a trusts and estates attorney, mostly at the Wall Street firm of Hawkins, Delafield & Wood is almost certainly no longer available to aspiring authors of any background. Neither, perhaps, is his literary career. We demand grimmer commitments these days — to say nothing of an overt self-promotion that would probably send Mr Auchincloss to Seneca's bathtub. One imagines, however, that he would not bring the old days back — his own old days, that is.

When Auchincloss was a child, he was already looking backward, talking to old people about when they were young, and so his memory in a sense extends back even farther than his ninety years, to the childhoods of the people who were grandparents when he was a child, which is to say, back to the New York of the eighteen-sixties and seventies, around the Civil War. That is the time when his historical fiction takes place: when brownstone New York was so small that his mother and her mother could drop half a dozen visiting cards in one block; when his grandmother knew Edith Wharton as a girl visiting Newport; and when the thought of a robber baron like Commodore Vanderbilt or Jay Gould being accepted into proper society was still unthinkable. Auchincloss believes that Wharton was right to call that time the age of innocence, and he seems to feel more nostalgia for that time than for his own, even though, or perhaps because, he was never there to see it. "I think," he once wrote, "I would rather see the old reservoir on Forty-Second Street or the original Madison Square Garden than I would any of the lost wonders of the ancient world."

A world in which Vanderbilt or Gould represents the outsider is a homogenous world indeed, one in which "nice" people behave differently from others simply because they can afford cleanliness, and not because they've been brought up in a different culture, as Mr Auchincloss's great-grandchildren presumably are today. A hundred years ago, the elites of the Eastern seaboard could pass as cadets of the English cousins whose fortunes they rejuvenated by marriage. Waves of assimilation and upward mobility have since eroded the great WASP headlands, washing away their high-mindedness along with — as Mr Auchincloss has come to recognize — their ingenuous cruelty.

Auchincloss has always enjoyed mocking the peccadilloes of his class, but he mocks them from the inside, with the affection of family. When outsiders do it, it's different — harsher, cruder, unforgiving. Outsiders can't tell the difference between snobbery and delicacy; between acquisition and self-fashioning; between cynical hypocrisy and quixotic self-blinding, a poignant desire to see one's own limited world as the best place it could possibly be. Outsiders, when they see the grand stupidity of the great world, find it outrageous or entertaining; they don't have the grace, as insiders do, to find it sad.

Copyright (c) 2008 Pourover Press