Reviewing the Book Review

Men on Horseback

13 June 2010

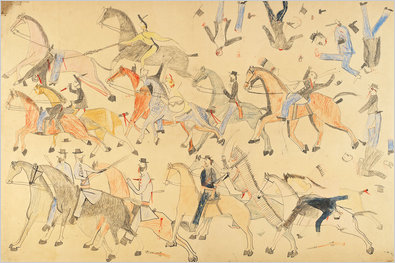

¶ Bruce Barcott on two books about the Indian Wars, The Last Stand: Custer, Sitting Bull and the Battle of the Little Bighorn, by Nathaniel Philbrick; and Empire of the Summer Moon: Quanah Parker and the Rise and Fall of the Comanches, the Most Powerful Indian Tribe in American History, by S C Gwynne. Although Mr Barcott indulges his yen to storytell, he eventually dispatches Mr Philbrick's subject and focuses on the much more interesting Quanah Parker.

Custer’s defeat shocked the nation, and there was little doubt even in 1876 that Little Big Horn represented an ignoble moment in American military history. So how did a monumental disaster turn into a courageous “last stand”?

Philbrick’s answer: A widow’s spin and show business. After her husband’s death, Elizabeth Custer, known as Libbie, embarked on a one-woman crusade to rehabilitate her beloved’s reputation through books and speaking engagements. Buffalo Bill Cody took the myth nationwide by ending his wildly popular Wild West Show with a Little Big Horn re-enactment and a call to avenge Custer’s glorious death. But really there was nothing to avenge but the poor judgment of a dangerously ambitious officer. The Battle of the Little Bighorn — the military engagement — was a foolish and entirely avoidable defeat. Custer’s last stand — the myth — was simply good show business.

If Custer illustrates how the spotlight of history sometimes shines on the wrong actor, Quanah Parker exemplifies the more deserving who get left in the shadows. One hopes a better fate awaits “Empire of the Summer Moon,” S. C. Gwynne’s transcendent history of Parker and the Comanche nation he led in the mid- to late 1800s.

It's not at all a disparagement of The Last Stand to hope that it will be the last book.

¶ Tom Carson on Role Models, by John Waters. Mr Carson has the wit to reach back into Baltimore history for a truly enlightening comparison.

If H. L. Mencken was the Sage of Baltimore, Waters is, at least, the parsley. Just for fun, consider what these two share: impudence, contrariness, uproarious insults to bourgeois values that made them controversial, then fashionable, then had them prematurely posing for their native-son statues. That they’d have horrified each other is just your usual Balmer lagniappe.

They’re also equally stubborn products of their times. At his most unreconstructed, Waters can brag, “I’m one of the few who voted for Obama because he was a friend of Bill Ayers,” which is both preening and stupid. Nonetheless, he’s more conscious than he used to be about the downside of his idea of fun. An initially sprightly tour of Baltimore’s dive bars (“the good ones have no irony about them”) sets up reminiscences of two local legends: a lesbian stripper who styled herself Lady Zorro and a Native American named Esther Martin, who ran a derelicts’ bar called the Wigwam “like an iron-fisted Elaine’s.” But then both women’s grown children tell him about their upbringings, packed with hair-raising episodes of selfishness, booze, abuse and neglect. Glumly, Waters asks himself, “Can living in a real John Waters movie ever bring any kind of joy?” If that’s a self-centered way of putting things, it’s also an accurate one.

¶ Deborah Solomon on Leo and His Circle: The Life of Leo Castelli, by Annie Cohen-Solal (translated by Mark Polizzotti). Having storytold at length, Ms Solomon focuses on what certainly seem to be objective problems with this book. We quote at length, happy not to feel guilty about watching a spanking.

For all its interesting disclosures, “Leo and His Circle” is compromised by careless writing and a breezy indifference to humble facts. The book is long on hyperbole and short on insight. The author deposits exclamation points at the end of too many otherwise unsurprising sentences, as if she were composing advertising copy for Champagne. “Nineteen fifty-eight: to all appearances a banner year!”

Misspelled names are rampant. The artist George Maciunas is identified as “Marciunas”; Max Kozloff, a former editor of Artforum magazine, surfaces as “Kozlof”; and the august critic Rosalind Krauss becomes “Rosalind Krausz,” as if she were Castelli’s long-lost Hungarian grandmother. Patterson Sims, an esteemed curator of American art now in his 60s, is referred to as “she.”

In her acknowledgments, Cohen-Solal graciously lists her assistants — all 23 of them. Is there such a thing as too many accessories to a biography? It would have been nice if one of them had taken a break from the demands of document digging in order to read a draft of the manuscript and pick out the sentences that contradict one another. For instance, the author refers admiringly to Castelli’s “program of stipends for . . . artists, a practice harking back to the Medicis, but completely innovative in the context of New York.” That’s incorrect, as the author surely knows; a few chapters earlier, she lauded the munificence of another Manhattan art dealer, Peggy Guggenheim, who in the ’40s had furnished Pollock with “the famous monthly stipend that had ensured his financial stability.”

Moreover, the author seems unfamiliar with the basic conventions of art dealing when she credits Castelli with “planting . . . satellite galleries, one after the next,” outside New York. She mentions David Mirvish in Toronto, Janie Lee in Dallas and Margo Leavin in Los Angeles, among many others — well-regarded dealers who did exhibit Castelli’s artists from time to time, but can no more be called his satellites than can the Louvre Museum. The strangest page of the book features a black-and-white illustration, a computer-generated “map of Castelli’s satellite galleries in North America” that imputes to him an expansionist mind-set and marketing stratagem that seem more applicable to the management of Red Lobster.

¶ Raymond Bonner on Ilustrado, a novel by Miguel Syjuco. A model of the helpfully enthusiastic review.

These are not caricatures, and this is not satire. Filipino readers will recognize figures in Syjuco’s cast, even though some of them are composites. The same handful of wealthy families rule the country today, much as they did 30, 40, 50 years ago, and they don’t do much to hide their contempt for the poor.

“Ilustrado” is being presented as a tracing of 150 years of Philippine history, but it’s considerably more than that. Just as this country is searching for its identity, its author seems to be searching for his own. What does it mean to live in exile? What does it mean to be a writer? The fictional Syjuco tells Salvador that he wants to change the world through his writing. “Changing the world is good work if you can get it,” his master replies. “But isn’t having a child a gesture of optimism in the world?”

“Ilustrado” received the Man Asian Literary Prize in 2008. Spiced with surprises and leavened with uproariously funny moments, it is punctuated with serious philosophical musings.

¶ Lesley Downer on Burmese Lessons: A True Love Story, by Karen Connelly. Happily, Ms Downer does not permit her disappointment with this book does not eclipse it.

Wherever she goes, Connelly takes notes. Eventually, these jottings resulted in a book of poetry, “The Border Surrounds Us,” and a harrowing novel, “The Lizard Cage,” about imprisoned Burmese dissidents. Nevertheless, it’s a little disappointing to read here of Connelly’s interviews with the pro-democracy leader Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, her meetings with dissidents in the jungle and her interviews with guerrilla fighters and be told so little of what was said. Instead Connelly is preoccupied with her emotional journey.

“Burmese Lessons” is an intimate account of a country, a relationship and a man — all three of which remain elusive. In the end, Connelly’s white skin and inescapable Westernness mean she can never be fully involved with Maung’s cause. After all, she will always be able to pick up and leave. Unlike her Burmese friends, she has a passport out. “For you,” one of them tells her, “it’s notes on paper. For me it’s my life.”

¶ Ben Ratliff on Nox, by Anne Carson. Mr Ratliff does a yeoman's job of explaining a very unusual item.

Anne Carson’s new book comes in a box the color of a rainy day, with a sliver of a family snapshot on the front. Inside is a Xerox-quality reproduction of a notebook, made after the death of her brother, including text and photographs and letters, pasted-in inkjet printouts, handwriting, paintings and collage. “Nox” has no page numbers, and it’s accordion-folded. It carries a whiff of visual art multiple or gift shop souvenir or “Griffin & Sabine.” But trust me: it’s an Anne Carson book. Maybe her best.

Carson, a university classics professor by trade, is usually described as a poet, though that’s not her problem. None of her books contain all verse in any traditional sense — not counting her translations — and some contain none. There’s not much poetry in this one, yet the whole thing is poetry of a kind you’re not used to. Her words are often not very melodious. Even on the hot subjects of desire and impermanence (sex and death and all their implications), she’s analytical, pedagogical, privately plain-spoken, stonily amused. In “Nox,” the linkage of ideas approaches a kind of music; the language works only in their service, without much extra show.

¶ Maria Russo on a brace of precocious memoirs, And the Heart Says Whatever, by Emily Gould; and How Did You Get This Number: Essays, by Sloane Crosley. Ms Russo clearly prefers one of these books to the other — inevitable, perhaps, but then again not. Bruce Barcott's multiple review of two books relating to the Indian Wars (see above) shows how related but not overlapping books can be fruitfully considered at the same time. This review suggests that two related and overlapping books ought to be judged separately.

That nameless “venue” is The New York Times Magazine, which made a cover story out of Gould’s tale of her emotional crash as a blogger, giving her work a new footing. Is omitting the publication’s name a faux-nonchalant brag? Is it a stand in solidarity with her passed-over high school self, designed to show indifference to the kind of East Coast institutional prestige that had eluded her earlier? Or maybe she is trying to erase the whole Times Magazine experience, which ended in a barrage of nasty online comments and a final estrangement from Joseph. In the end, she morosely admits she is betraying him yet again “now, writing this.” All of these essays are drifty, which becomes more and more of a liability. She leaves things on an especially unsettled note, still sorting through feelings about that doomed relationship, still groping to articulate lessons she seems certain are buried somewhere in the daily details of her New York life.

Sloane Crosley is also a young woman from suburbia with a publishing job in New York, but where Gould seems to want her story to be shocking and modern, Crosley goes for charming and old-fashioned. She mostly succeeds in “How Did You Get This Number,” her second collection of essays about making it, zanily, in the big city. Crosley is like a tap-dancer, lighthearted and showmanlike, occasionally trite, but capable of surprising you with the reserves of emotion and keen social observation that motivate the performance. Her subjects tend toward New York chestnuts: near-heroic apartment searches, bad smells in taxis, New Yorker-out-of-water trips to exotic places.

¶ Christopher Beha on One More theory About Happiness: A Memoir, by Paul Guest. Mr Beha's moving review of this paralyzed poet's memoir reflects attractively on his poetry as well.

But Guest is no confessionalist. He comes at his own catastrophe sidelong, alluding to it as another poet might to Stevens or Pound. “O hearts fat with custard, and sweet / forgive that I move at all,” he writes in one poem. Or, elsewhere: “I feel better that none of me / works well at all.” These poems — angry, funny, canny — do not depend for their meaning on the facts of their maker’s biography, but they are enriched by it.

Now, in his memoir, “One More Theory About Happiness,” Guest writes more directly than ever before about his paralysis. After a short prologue, the book begins with a recounting, harrowing in its matter-of-factness, of the accident that has shaped his life. Guest was 12 years old, attending a sixth-grade graduation party at a teacher’s house, when he and another boy set off on a pair of borrowed bicycles. As he lost control of his bike, Guest squeezed the hand brake and discovered it broken:

“I was resigned to the inevitability of crashing, and in those few seconds I had before the bike would be dangerously fast I decided it was better to crash on grass than to land on the asphalt. . . . What I did not know, what I could not see, would be what changed the rest of my life. At the bottom of the slope, a drainage ditch ran beside the road, overgrown with weeds and thick tussocks of grass. I hit the ditch still traveling at speed. I was thrown from the bike, over the handlebars, catapulted, tossed like a human lawn dart into the earth.”

¶ Jess Row on The Spot: Stories, by David Means. The most interesting thing about this mixed review — favorable at first, then not so much — is Mr Row's attempt to step back from final judgment.

But to read “The Spot” in its entirety, or his previous, equally virtuosic collections “Assorted Fire Events” and “The Secret Goldfish,” is to see a writer with a sensibility that owes more to Beckett: a God-like disinclination to see his characters as anything more than case studies, or as he puts it in the title story, “one more textbook case of discard and loss, another suicide fished out of the waters” or, in “The Junction,” “just a snoring mound up in the weeds.”

In the aggregate, though, as powerful as Means’s work is, this kind of existential certainty can begin to feel reflexive and repetitive, a bit of an aesthetic tic. Sometimes in powerfully formed collections one uncharacteristic story can throw the rest of the book into sharp relief, and this is the case here with “A River in Egypt,” in which a young father from a New York suburb takes his son to the hospital to be tested for cystic fibrosis. Cavanaugh, the father, has things Means only very rarely gives his characters — a job, a family, an identifiable speaking voice, ordinary domestic concerns and irritations — and as a result we begin to wince and shudder in a very familiar way as he makes a disastrous and humiliating mess of things, only prolonging the agony of the final positive diagnosis. It’s hard not to look at this story, which not only risks sentimentality but exults in it, and wonder if we are supposed to see Cavanaugh, too, as a case of “discard and loss,” and if not, why only he, out of the 13 protagonists here, deserves the privilege of a distinct humanness.

This isn’t so much a critique of Means’s work to date as a question about what he will do next, having written, in the last two decades, three collections that speak with one immutable voice.

¶ Adam LeBor on The Ghosts of Martyrs Square: An Eyewitness Account of Lebanon's Life Struggle, by Michael Young. Recalling that Mr LeBor is the author of a book about "Arabs and Jews in Jaffa," we're inclined to insist that all books about the Middle East be covered by reviewers with no connection to the region.

“The Ghosts of Martyrs Square” is studded with evocative anecdotes like that one, which tantalize the reader but regrettably are not properly incorporated into the narrative. Perhaps Young lacked the confidence to write more in the first person (there are no entries at all in the index for Young, Michael) or to tell us more about his mixed American-Lebanese heritage and his life as an editor on an English-language newspaper. Can he really publish any opinion he wants? The reader longs for details about Young’s nights of drinking at the Chase while Israeli jets screamed overhead. That would have added necessary color and human drama to what is an incredibly complex political story.

¶ Tobin Harshaw on Chef, a novel by Jaspreet Singh. We cannot see the use of reviews that include passages such as this:

But Kip isn’t going to be hurried onto any fast track. Instead, he finds his true calling amid the redolent spices of the kitchen. While he’s as profane and pigheaded as any clichéd American Army sergeant, Chef Kishen proves to be a culinary guide with an unexpected spiritual dimension. “Before cooking he would ask: Fish, what you like to become? Basil, where did you lose your heart? Lemon: it is not who you touch, but how you touch.” Unfortunately, the mentor-apprentice friendship is more lovingly described than the culinary atmosphere. Despite an elaborate array of ingredients, techniques and dishes, the associated sensory phenomena fail to be translated into evocative prose. “Chef” is a cold meal, with Kip at its gelid center.

¶ William Easterly on The Rational Optimist: How Prosperity Evolves, by Matt Ridley. This review is an unhelpful as it is unsympathetic.

Actually, combining technologies to make new technologies is another favorite idea of Ridley himself. But he is too casual about the logic of it all: in his cringe-inducing metaphor, “ideas have sex.” For example, the telephone had carnal relations with the computer, and their love child was the Internet.

Ridley strains to fit the notion of ideas having sex into what he himself calls the “Procrustean bed” of his “gains from exchange” story of progress. But sharing ideas is not the same as exchanging goods. It is often accidental and involuntary: it’s hard to keep a good idea a secret, so strangers are likely to gain from your idea without your getting anything in exchange. The dissemination of ideas is therefore more mysterious than the gains from exchange of goods, and Ridley ultimately leaves us with logical loose ends rather than explanations.

¶ Leslie Gelb on The Icarus Syndrome: A History of American Hubris, by Peter Beinart. Mr Gelb appears to believe that the publication of Mr Beinart's book is the occasion for him to argue against its ideas. We hope that he enjoyed himself.

In the end, Beinart can’t resist exhuming Icarus one last time — to great excess. He says that his book aims to help President Obama overcome “the beautiful lie” — “a series of assumptions about American omnipotence that, if not challenged, threatens to drive our foreign policy deeper into the red.” Frankly, it’s difficult to unearth even one serious foreign policy expert today who believes the United States is omnipotent. To me, the gravest danger is to assert the primacy of American economic renewal and then ignore the tough foreign and domestic choices that must attend this priority. To his credit, Beinart calls for a renewal of American schools, politics and economic vitality. But these good ideas dissipate in a haze of hubris.

¶ Barry Gewen on Neoconservatism: The Biography of a Movement, by Justin Vaïsse. This strongly favorable review distinguishes Mr Vaïsse's book from screeds that probably oughtn't to be published in codex format.

This definitional question, and in particular neoconservatism’s extraordinary transformation, is the principal subject of “Neoconservatism: The Biography of a Movement,” by Justin Vaïsse, a French expert on American foreign policy who is currently a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution. It is essential reading for anyone wishing to understand the contours of our recent political past. Vaïsse is a historian of ideas. “Neoconservatism” demonstrates, among other things, that ideas really do make a difference in our lives.

¶ David Oshinsky on In the Place of Justice: A story of Punishment and Deliverance, by Wilbert Rideau. A classically poor review, this piece simply retells Mr Rideau's arresting story without bothering to convey a sense of his manner of telling it.

As reforms were implemented, the violence decreased. The new Angola owed much to Rideau’s skills as editor, gadfly and ombudsman. While in prison, he became a national celebrity, appearing on “Nightline” with Ted Koppel and winning journalism’s coveted George Polk Award. Rideau is hardly modest about it all. His memoir is stuffed with self-serving vignettes in which he persuades a skeptical warden or some other doubting official to make a change that dramatically brightens convict life or helps defuse a riot. And he is especially disdainful of “outside” prison activists like Sister Helen Prejean of “Dead Man Walking” fame for meddling in a world he claims they can’t possibly understand.

Mr Oshinsky's unconscious arrogance is insupporable. ¶

¶ Graham Farmelo on Quantum: Einstein, Bohr, and the Great Debate About the Nature of Reality, by Manjit Kuman. So far as Book Review evaluations of science books goes this one can only be dismissed as standard and poor.

“Quantum” is a wide-ranging account, written for readers who are curious about the theory but want to sidestep its mathematical complexities. It’s full of a surprising amount of detail, perhaps rather more than most readers will want. The story is chock-full of colorful characters, including the two physicists who independently set out the first two versions of the theory, which initially appeared to be quite different. The first was the young Werner Heisenberg, not two years past his doctorate, fun-seeking and intensely competitive, not least at the Ping-Pong table. The other was the older Erwin Schrödinger, an Austrian polymath who scandalized his conservative colleagues by showing up at conferences in his climbing gear, sometimes accompanied by an adolescent lover.

¶ Stephen Burn on Witz, a novel by Joshua Cohen. Although Mr Burn struggles manfully to find things to like in this immensely self-important novel, he does not assess its "drop everything and read me" command.

Like a sermon described in the novel, the language in “Witz” is “scripted to sound,” designed to capture the verbal distortions of East Coast speech. We hear of “Mortal Beach” and “Soygens General.” But while the scale of the sentences comfortably exceeds the lung capacity of most readers (Cohen isn’t afraid to unfurl a five-page sentence), the prose constantly highlights language’s sonar qualities: “At lot’s edge, last scattered lungs of leaves still hang from the boughs, breathe uneasy.” Cohen’s sentences are fluid, living things: “This lulling, ship’s loll, . . . a remnant, a reminder of the darkness, . . . and, flying across that sky a fish lands on the deck, at the forecastle, the fallen castle.”

The way words evolve across the sentence — “lull” becoming “loll,” “remnant” mutating into “reminder” — is appropriate because this book is so preoccupied with inheritance and change. In a key late passage, Cohen explicitly identifies the burden of Jewish history, especially the Holocaust, as the novel’s inheritance, which helps to explain why “Witz” relies so consistently on negation:

¶ A new New Yorker anthology, The Only Game in Town: Sportswriting From The New Yorker has no need for the Book Review's attentions in general or David Kelly's in particular. ¶ Adam Ross's generally favorable review of Eleanor Catton's The Rehearsal leaves one unsure that this novel is aimed at adults. .

Permalink | Portico | About this feature

Copyright (c) 2010 Pourover Press