Reviewing the Book Review

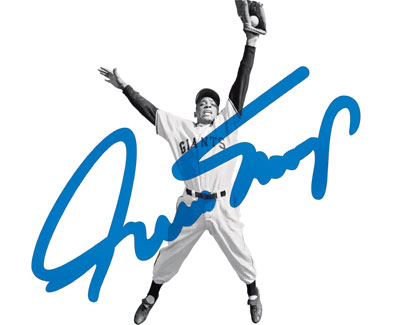

Say Hey

28 February 2010

¶ Pete Hamill gives James Hirsch's Willie Mays: The Life, the Legend one of those baseball paeans that verges so pressingly on the Homeric that the subject of the review comes to merit coverage by proxy.

In this book, Hirsch evokes a time now gone, one he himself didn’t experience. He was born in 1962, and never saw Mays play. But he has studied the films and videos. He has drawn on newspaper and magazine articles from that era, and previous books about Mays (most notably Charles Einstein’s “Willie’s Time,” published in 1979). He has interviewed many people, including Mays, who has “authorized” this biography. The result: Hirsch has given us a book as valuable for the young as it is for the old. The young should know that there was once a time when Willie Mays lived among the people who came to the ballpark. That on Harlem summer days he would join the kids playing stickball on St. Nicholas Place in Sugar Hill and hold a broom-handle bat in his large hands, wait for the pink rubber spaldeen to be pitched, and routinely hit it four sewers. The book explains what that sentence means. Above all, the story of Willie Mays reminds us of a time when the only performance-enhancing drug was joy.

¶ Gilbert Sorrentino's posthumously-published novel, The Abyss of Human Illusion, gets an ultimately inadequate review from Roger Boylan. Mr Boylan likes the book and likes Sorrentino, too, but both, in his hands, appear to be arch and difficult.

Accordingly, “The Abyss of Human Illusion,” with its 50 set pieces labeled by Roman numerals — the first a mere 130 words long, the last approximately 10 times that — is not so much a novel as a random collection of mini-narratives, some of them variations on previous Sorrentino themes, one a homage to Rimbaud, another a nod to Saul Bellow. They are very entertaining. A lesser writer, or one with less humor, would have allowed himself to wallow in contempt and schadenfreude, and those feelings are certainly present, but Sorrentino, like the great Roman satirists in his ancestry — Juvenal, Suetonius, Martial — has an antic disposition that rises above all that and makes us laugh, not cry

¶ Richard Bausch's fictional territory is squarely laid out in Maria Russo's warmly favorable review of his new collection, Something Is Out There: Stories.

An older man is on his fourth wife. She’s much younger; in fact, she happens to be his former student. And now he’s apparently walked out on her too. That’s the setup for the story “The Harp Department in Love.” But if it seems to promise a walk down some familiar literary lane — telling, say, a tersely lyrical tale of the wreckage caused by restless, self-defeating men, or depicting a grand tragedy of never-satisifed masculine desire — rest assured that because it’s a Richard Bausch story it will attend to the predicaments of the American male with insight and flair, even as the struggles of his female counterpart are treated with an equally interested eye.

¶ Alida Becker joins the flock of reviewers who have been unable to resist quoting Peter Hessler's very amusing commentary on Chinese drivers, from Country Driving: A Journey Through China From Farm to Factory.

“It’s hard to imagine another place where people take such joy in driving so badly,” Hessler writes. Beijingers drive the way they used to walk — in packs and without signaling. “They don’t mind if you tailgate, or pass on the right or drive on the sidewalk. You can back down a highway entrance ramp without anybody batting an eyelash. . . . People pass on hills; they pass on turns; they pass in tunnels.” In other words, driving requires improvisation and creative flouting of the law — which is also a pretty apt description of the average citizen’s technique for maneuvering through the warp-speed transitions of Chinese society.

¶ Ben Sisaro's guardedly favorable review of Bill Flanagan's Evening's Empire approaches the novel as if it were a non-fiction memoir, with little thought for the writing — no small oversight, given the book's exceptional length (648 pages).

That, at least, is the point of view in “Evening’s Empire,” a rock novel by Bill Flanagan as long as a Yes concept album and as wittily observed as a Kinks song. Following the members of a second-tier British band called the Ravons, it winds through the standard historical mileposts of the last 40-odd years — the fizzy mid-’60s, the turgid and bearded ’70s, the reunion tours and charity mega-concerts since the ’80s — and leads to a sobering coda: the end of the party, the twilight of the rock gods.

¶ Eric Puchner's Model Home gets a warm dollop of storytelling from Marisa Silver, with occasional highlights of fine writing. .

Puchner is a tender, humane observer of family life, and his lithe prose deepens our understanding of his characters. When Lyle succumbs to the advances of the awkward and serious guard at her community’s gatehouse, for instance, her youth is made heartbreakingly explicit: “What she remembered most was Hector opening the condom wrapper with his teeth, like a McDonald’s ketchup.” Or here’s Dustin, noticing the seductive charms of his girlfriend’s dark and self-destructive younger sister: “The rips in her jeans opened and closed, like little mouths, when she walked.” The writing is attuned and specific, and it reveals how the family starts falling apart as each member grasps for identity in this new, strange place.

¶ Elyssa East's tepid review of Deborah Blum's The Poisoner's Handbook: Murder and the Birth of Forensic Medicine in Jazz Age New York is too dissatisfied to be helpful.

Ultimately, The Poisoner’s Handbook fascinates more than it satisfies. Crime-solving tales and skillfully constructed scenes rife with memorable anecdotes hold the reader’s attention, but the detailed chemical explanations and meticulous accounts of lab procedures that fill each chapter make for a routine and predictable structure. For all Blum’s material has going for it, the book leaves one yearning for deeper insights into Norris’s and Gettler’s motivations and a more forceful conclusion. Nonetheless, The Poisoner’s Handbook is an inventive history that, like arsenic mixed into blackberry pie, goes down with ease.

¶ Robin Kelley doesn't feel that Nadine Cohodas has done enough to explain the behavior of her subject in Princess Noire: The Tumultuous Reign of Nina Simone. In a book about a performer, this is an unhelpful sidelight.

After establishing Simone’s musical genius, international success and political prominence, Cohodas details her long downward spiral. To the author’s credit, she tries valiantly to keep our attention on the stage and Simone’s music, even when it is subpar, and even when Simone’s life becomes a litany of self-destructive acts and bitter disappointments. Yet while Cohodas provides vivid descriptions of Simone’s behavior, she offers very little by way of explanation. How shy Eunice Waymon became a demanding diva almost overnight remains a mystery. Not until the last 50 pages do we learn that Simone probably suffered from schizophrenia.

¶ Jason Goodwin appears to believe that, because Paul Theroux wrote it, A Dead Hand: A Crime in Calcutta needs no explanation. As a result, it comes across as pointless and jejune.

Yet Theroux’s approach to the genre is gloriously diffident. Jerry Delfont is no Philip Marlowe, no Hercule Poirot; he’s neither a great investigator nor engaging company. He’s simply a jobbing travel journalist who falls for a mysterious American do-gooder called Mrs. Unger after she writes him a note in purple ink, asking for his help. Later she provides him with pages of excruciatingly dull tantric sex and a murder mystery that no one — down to Theroux himself, as we will see — seems remotely bothered by or interested in solving until the last few chapters.

¶ Judith Newman's impatient review of Dani Schapiro's Devotion: A Memoir makes the book sound absolutely intolerable.

Yet after a while her anhedonia becomes less understandable and more exasperating. Alone in her house with her espresso machine and her “bottles of gourmet vinegar, bee pollen, truffle oil,” she reflects, “I’ve been having trouble maintaining a sense of solitude.” And while she goes on to explain what she means (“the kind of silence inside of which one can transact some private business with the fewest obstacles, in Thoreau’s words”), one finds oneself thinking, perhaps ungenerously, that this pondering is a luxury of the privileged. The searching seems to bring Shapiro nothing but more tsoris. “At times I was convinced that I had made a huge mistake, delving this intensely into spiritual matters. Was I becoming one of those earnest, humorless people?” (My marginal note, I confess: “Yes.”)

¶ At no point in his review of About a Mountain, by John D'Agata, does Charles Bock explain what the suicide of a teenager has to do with a baleful contemplation of the dangers of storing nuclear waste at Yucca Mountain.

Indeed, D’Agata’s prime reason for steering us through all the glittery factoids and scholarship is to take us to the ledge of what knowledge can provide, and to document how perilous it can be to stand on that ledge. These 200 pages are nothing less than a chronicle of the compromises and lies, the back-room deals and honest best intentions that have delivered us to this precarious moment in history. The book is a shouted question about who we are and how we move forward. This is how art is made. And the final pages of “About a Mountain,” which consist of a single long paragraph leading through the last evening of Levi Presley’s life, are unquestionably art, a breathtaking piece of writing.

¶ The first paragraph of Louisa Thomas's mixed review of Heidi Durrow's The Girl Who Fell From the Sky must mean something, but we've no idea what it is.

There’s a reason many great social justice novels are written as historical fiction or contain elements of fantasy or allegory: This builds a certain crucial distance into their storytelling. Heidi W. Durrow is the daughter of an African-American serviceman and a white Danish mother, and her first novel was, according to her publisher, “inspired by true events.” On the face of it, the story of a biracial girl growing up in 1980s America, grappling with confusion over both her identity and a complicated, mysterious family history, couldn’t be more timely or important. But in the moments when Durrow’s novel seems to tackle its big themes most self-consciously — when it appears written for the Age of Obama — it can be predictable, even dull. It’s when it approaches the questions of identity and community more subtly and indirectly that The Girl Who Fell From the Sky can actually fly.

¶ Simon Akam gives Forest Gate, a novel by Peter Akinti that is set in the East End of London, an unhelpfully script-doctorish review.

This fear might make sense for Baldwin’s American characters, but it doesn’t for Akinti’s upper-class British barrister. Without a doubt there are feudal absurdities to British society — its accents are like barcodes, rife with data on birth and education that the native ear can decipher. But one advantage of a country that fractures so dependably on class lines is that it tends not to on racial ones: a black man with the trappings of privilege can be secure in that privilege. Akinti, borrowing American rhetoric, fails to acknowledge that calcified Britain allows an alternative route to racial acceptance precisely because of the importance attached to things like pronunciation and monogrammed cuffs.

¶ Mike Peed doesn't much like Henning Mankell's latest crime novel to appear in English, The Man From Beijing, and he likes Laurie Thompson's translation even less. That's not very helpful.

There’s a hard-boiled gruffness to Mankell’s prose, although his story often reads like the product of an oral tradition, dotted with aphorisms. (“White men smelling of spirits were always more unpredictable than sober ones.”) Most grating, however, is Laurie Thompson’s translation, full of awkward syntax and clichés. (To what degree this originates with Mankell is hard to know.) One character is “not yet defeated, once and for all,” while another “should have understood, but refused to accept what she really did understand.” “Ignorance is bliss”; “The devil is always in the details”; and “If you want to make an omelet, you have to break an egg.”

If a Raymond Chandler effect is the goal, the humdrum plot interferes.

Permalink | Portico | About this feature

Copyright (c) 2010 Pourover Press