Reviewing the Book Review

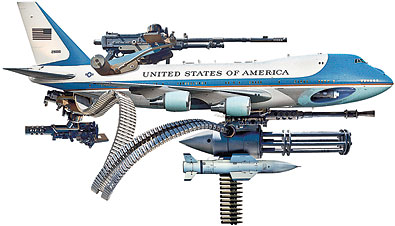

Who Gets to Declare War?

24 January 2010

¶ Walter Isaacson reviews two books about executive-branch war powers, John Yoo's Crisis and Command: This History of Executive Power from George Washington to George W Bush and Garry Wills's Bomb Power: The Modern Presidency and the National Security State in the space that either one would deserve on its own, and manages, while saying nothing unfamiliar to the sort of reader who would be interested in this review, to make neither book sound worth reading.

What Yoo and Wills have thus wrought in these dueling chronicles could be called “advocacy history,” in which scholarly analysis and narrative are marshaled into the service of a political argument. “Some may read this book as a brief for the Bush administration’s exercise of executive authority in the war on terrorism,” Yoo writes. “It is not.” But it most certainly is precisely that, and a very rollicking and thoroughly researched brief as well. As he says in summation, the Bush administration “made broad claims about its powers under the president’s constitutional authorities, but this book shows that it could look to past presidents for support.”

Wills, as befitting his well-earned gravitas, is somewhat more literary but no less argumentative, especially at the end of his book, when he recounts the arguments made by Yoo and his Bush administration colleagues, like one memo calling the Geneva Conventions “quaint” and “obsolete.” “Perhaps in the nuclear era, the Constitution has become quaint and obsolete,” Wills grumbles.

¶ Hilary Mantel, author of the noted novel Wolf Hall, about Thomas Cromwell, gives Alison Weir's historical account of Anne Boleyn's trajectory, The Lady in the Tower: The Fall of Anne Boleyn, a generous review, politely mentioning the alternative views of other historians instead of dismissing this one's.

Alison Weir, a respected and popular historian, has already written about Anne in “The Six Wives of Henry VIII” and “Henry VIII: The King and His Court.” Her new book focuses on the last few months of Anne’s life. She has sifted the sources, examining their reliability. Doubts have already been cast on Weir’s assumptions; the historian John Guy has recently suggested that two sources she took to be mutually corroborating are in fact one and the same person. This doesn’t invalidate her brave effort to lay bare, for the Tudor fan, the bones of the controversy and evaluate the range of opinion about Anne’s fall. Some of her findings, she admits, contradict her previous beliefs; for instance, she no longer thinks that Anne was pregnant at the time of her execution. She notes that there is no evidence for the controversial theories put forward in Retha Warnicke’s 1989 book “The Rise and Fall of Anne Boleyn.” Warnicke suggested that Anne had miscarried a deformed child, and so was thought guilty of witchcraft, but Weir gives more credence to Warnicke’s suggestion that Anne’s male friends, her brother in particular, were involved in homosexual acts thought deviant at the time. No such allegations surfaced in court, but they may have contributed to a climate of moral panic, as sexuality and witchcraft were linked in the imagination of the time. When Thomas Cromwell gave an account of the destruction of the Boleyns in a letter to English ambassadors in France, he declined to give details, as “the things be so abominable.”

¶ Jay McInerney rather disappointingly joins the chorus of reviewers who want a second Then We Came to the End instead of the novel that Joshua Ferris has actually written, The Unnamed. It's as though the taste of the first book makes it impossible to enjoy the second.

Tim’s travels don’t really take him anywhere, literally or figuratively, until finally he makes a concerted effort to return to New York, fighting to make headway against the random dictates of his compulsion. Even as he ignores the landscape Ferris scrupulously documents the deterioration of Tim’s body and his mind as he struggles to return to Jane, who is dying of cancer. When he visits her in the hospital in between walks, she is astonished to find how little he notices on his travels. He finally starts to observe the world around him so that he can share the details with her, but for this reader, it’s too little, way too late.

Remember when Paul McCartney went classical with “Liverpool Oratorio”? Me neither. As a fan of “Then We Came to the End” I can admire Ferris’s earnest attempt to reinvent himself, but I can’t wait for him to return to the kind of thing at which he excels.

The snarky comparison to Sir Paul is exactly the sort of touch that Mr McInerney ought to avoid.

¶ Charles Isherwood's not-unfavorable review of Free For All: Joe Papp, the Public, and the Greatest Theatre Story Ever Told, an oral history compiled by Kenneth Turan and Joe Papp, with the assistance of Gail Merrifield Papp, suggests that this is exactly the sort of book — chatty, vivid, and frequently bogged-down in minutiae — that one would expect it to be.

The great stories of Papp’s David-and-Goliath successes — for example, the battle with the mighty Robert Moses over keeping Shakespeare in the Park free — are delightful to re-encounter through the voices of the people involved, like hearing the details of historic ballgames retold by the participants, inning by inning. The histories of the major artistic relationships in Papp’s life — his long collaboration and painful parting with his loyal associate Bernard Gersten, his fatherly love for the playwright David Rabe — are also examined from all sides. (There is little or nothing about his sometimes tumultuous personal life.) The inclusion of extensive input from his early collaborators makes clear that while Papp was the driving force in the creation of the Shakespeare Festival and the Public Theater, many dozens of others played significant roles.

¶ It's hard to know for whom Sandeer Jauhar has written his guardedly favorable review of Atul Gawande's The Checklist Manifesto: How to Get Things Right, or, for the matter of that, what this review is doing in the Book Review.

Yet despite its evangelical tone, “The Checklist Manifesto” is an essential primer on complexity in medicine. Doctors resist checklists because we want to believe our profession is as much an art as a science. When Gawande surveyed members of the staff at eight hospitals about a checklist developed by his research team that nearly halved the number of surgical deaths, 20 percent said they thought it wasn’t easy to use and did not improve safety. But when asked whether they would want the checklist used if they were having an operation, 93 percent said yes.

Good to know.

¶ Neil Genzlinger's glib review of David Thomson's The Moment of Psycho: How Alfred Hitchcock Taught America to Love Murder does no one a service. .

It’s interesting stuff for anyone who has watched Psycho 50 times (or has watched it just before reading this book), but who except an unbalanced film student has these days, when the movie registers as a nugget of silliness wrapped in retro cool? Sure, Thomson is merely doing what serious film critics do: dissecting movies the way a coroner probes a corpse, piling far more import onto them than their creators ever intended. And in the best parts of the microanalysis stretch of the book, he is deliciously eloquent, as when he at last comes to the end of Marion’s journey:

“She takes off her robe. She steps into the shower. This is the moment.”

But the exercise feels a little like a last gasp. ... Maybe alongside all the groundbreaking that Thomson attributes to Psycho there is room for a companion theory about the film: that it was the last movie about which a book like The Moment of Psycho could be written.

¶ Steve Coates's warmly sympathetic review of David Malouf's variations on themes taken up by Homer, Ransom, persuades us that this book is not a post-modern stunt.

It will inevitably be said that Malouf’s novel “subverts” or “undermines” the “Iliad,” but his impressive knowledge of the epic’s more abstruse themes and features and their subtle redeployment belie such a rote notion; “Ransom” disavows the flip free association often seen in the modern reshaping of Greek myth. On the level of plot, even his most eccentric (and unpersuasive) diversion — the invention of a lower-class Trojan who teaches the regally sequestered Priam the joys of dangling his feet in a stream and an appreciation for the beauty of mules — is touchingly redeemed by the man’s deep need, after the fall, to tell his tale. “His listeners do not believe him, of course. He is a known liar. He is a hundred years old and drinks too much.” In other words, an epic poet in parodic embryo.

¶ Stephen Mihm summarizes Joyce Appleby's The Relentless Revolution: A History of Capitalism as a gallery of bold self-starters.

But make no mistake: this is a book that emphasizes capitalist enterprise, not resistance to it. The individual entrepreneur is at the center of her analysis, and her book offers thumbnail sketches of British innovators from James Watt to Josiah Wedgwood. She continues on to the United States and Germany, giving readers a whirlwind tour of the lives and achievements of a host of men whom she calls “industrial leviathans” — Vanderbilt, Rockefeller and Carnegie in the United States; Thyssen, Siemens and Zeiss in Germany. All created new industries while destroying old ones.

¶ Vali Nasr's Forces of Fortune: The Rise of the New Muslim Middle Class and What It Will Mean for Our World may be the "outstanding new book" that Michael Totten says it is, but his review suggests a work of wishful thinking.

Nasr brilliantly narrates the tortured histories of the middle classes in Pakistan and Iran, torn between secular dictators like Shah Mohammed Reza Pahlavi and Gen. Pervez Musharraf on one side, and the Ayatollah Khomeini’s Islamic Republic and the Taliban on the other. The road to a new Middle East, where Turkey is the norm rather than the exception, will be a long and perilous one. Even so, “Forces of Fortune” is as hopeful as it is sobering, and Nasr makes a convincing case for optimism tempered with caution and patience.

¶ It would have been better if Paul Hockenos's storytelling review of Mary Elise Sarotte's 1989: The Struggle to Create Post-Cold War Europe had consisted of nothing more than the following paragraph.

But this order of things was hardly inevitable, as Mary Elise Sarotte, a professor of international relations at the University of Southern California, reminds us in “1989: The Struggle to Create Post-Cold War Europe.” Between the wall’s opening (November 1989) and Germany’s unification (October 1990), history lurched forward with no fixed destination. Sarotte describes a host of competing conceptions of post-cold-war Europe that flourished, mutated and perished in the maelstrom of events that led up to German unity. In the end, the visions of President George H. W. Bush and Chancellor Helmut Kohl prevailed — which may not necessarily have been the best of all possible outcomes, though Sarotte stops short of this conclusion.

Permalink | Portico | About this feature

Copyright (c) 2010 Pourover Press