Reviewing the Book Review

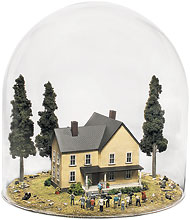

Glass Menagerie

7 November 2009

¶ James Parker's enthusiastic review of Stephen King's cautionary fable, Under the Dome, renews the judgment that Mr King is a thoughtful and serious writer, but not a very good one.

As for the prose, it’s not all smooth sailing. Given King’s extraordinary career-long dominance, we might expect him at this point to be stylistically complete, turning perfect sentences, as breezily at home in his idiom as P. G. Wodehouse. But he isn’t, quite. “Then it came down on her again, like unpleasant presents raining from a poison piñata: the realization that Howie was dead.” (It’s the accidental rhyme of “unpleasant” and “presents” that makes that one such a stinker.) I felt the clutch of sorrow, too, when I read this: “What you’re planning is terribly dangerous — I doubt if you need me to tell you that — but there may be no other way to save an innocent man’s life.”

"Writing flat-out keeps him close to his story, close to his source." An excellent description of a good first draft!

¶ Harold Bloom is very polite about David Nokes's Samuel Johnson: A Life, although he labels the book "workmanlike." This does not excuse his using the review as an occasion for reflecting upon "the canonical critic." Nor does it render the following favorable comment helpful.

Nokes is particularly moving and informative on Johnson’s relation to his Jamaican manservant, Frank Barber, a freedman who essentially became Johnson’s son, though without formal adoption. A childless widower, Johnson willed Barber his estate and effects, hoping that the young man could prosper without him.

¶ Liesl Schillinger persuasively positions Barbara Kingsolver's new novel, The Lacuna, as an important and satisfying novel.

The Lacuna can be enjoyed sheerly for the music of its passages on nature, archaeology, food and friendship; or for its portraits of real and invented people; or for its harmonious choir of voices. But the fuller value of Kingsolver’s novel lies in its call to conscience and connection. She has mined Shepherd’s richly imagined history to create a tableau vivant of epochs and people that time has transformed almost past recognition. Yet it’s a tableau vivant whose story line resonates in the present day, albeit with different players. Through Shepherd’s resurrected notebooks, Kingsolver gives voice to truths whose teller could express them only in silence.

¶ David Kirby's warm enthusiasm for Amy Gerstler's new volume of poems, Dearest Creature, inspires him to quote generously from the work. Anyone likely to respond to Ms Gerstler will be roped in by this model review.

As grave as they are amusing and always bittersweet, these poems pay up again and again. “Dearest Creature” is an A.T.M. — the letters standing, in this case, for “artistic thrill machine.” In Amy Gerstler I trust.

¶ Hanna Rosin really likes Barbara Ehrenreich's critique of American optimism, Bright-Sided: How the Relentless Promotion of Positive Thinking Has Undermined America — the reviewer is positively grateful for the camaraderie — but she believes that Ms Ehrenreich is too willing to overlook the complicity of ordinary Americans.

“Where is the Christianity in all of this?” Ehrenreich asks. “Where is the demand for humility and sacrificial love for others? Where in particular is the Jesus who said, ‘If a man sue you at law and take your coat, let him have your cloak also?’ ” Ehrenreich is right, of course, in her theological critique. But she misses a chance to dig deeper. I have spent some time in prosperity churches, and as Milmon F. Harrison points out in “Righteous Riches,” his study of one such church, this brand of faith cannot be explained away as manipulation by greedy, thieving preachers. Millions of Americans — not just C.E.O.’s and megapastors but middle-class and even poor people — feel truly empowered by the notion that through the strength of their own minds alone they can change their circumstances. This may be delusional and infuriating. But it is also a kind of radical self-reliance that is deeply and unchangeably American.

¶ As a rule, we try not to interpose our own take on a book that we're reading when evaluating the review that it has gotten in the Book Review. In the case of William Shawcross's The Queen Mother: The Official Biography, we must make an exception. Demonstrating that he is a hardly a reader whose opinion of this book is worth having, Joe Queenan writes,

Adhering to the principle that royals should be seen but not really heard, the queen mother seems to have said little that was truly interesting.

The judgment is unsurprising, because Mr Queenan is a very different sort of comedian from Mr Shawcross's subject.

¶ Joanna Scott reports that, if Last Night in Twisted River is any indication, John Irving is not interested in appealing to serious readers — readers, that is, for whom novels need not be "made serious."

Given Irving’s skill, it’s especially frustrating to see him working so hard to spell out the import of the fiction. Even if some of the explanations are meant to be inflected with irony (we shouldn’t necessarily believe everything this narrator tells us), they still aren’t convincingly integrated with the events and characters. The coy hints of connections between the author and the narrator have been forced onto a plot that can’t accommodate them, and the fact that Danny is a famous novelist too often seems a mere contrivance, giving Irving a convenient opportunity to include rambling background information and to air his own ideas about writing. In his bid to make something “serious,” Irving has risked distracting readers from what otherwise could be a moving, cohesive story.

¶ Rhoda Janzen, author of Mennonite in a Little Black Dress, is lucky to have Kate Christensen rooting for her book.

Janzen is as sharp about the cognoscenti and academics she now lives among as she is about Mennonites and her family’s eccentricities. Her tone reminds me of Garrison Keillor’s deadpan, affectionate, slightly hyperbolic stories about urbanites and Minnesota Lutherans, and also of the many Jewish writers who’ve brought mournful humor to the topics of gefilte fish and their own mothers, as well as to the secular, often urban, often intellectual world they call home now. It’s the narrative voice of the person who grew up in an ethnic religious community, escaped it, then looked back with clearsighted objectivity and appreciation.

¶ Mark Harris's favorable review of Mitchell Zukoff's Robert Altman: The Oral Biography finds it to be something like the punishment that fits the crime.

As a form of Hollywood storytelling, oral history has its drawbacks — too often, testimony substitutes for authorial perspective, and those unwilling or unable to speak for themselves can be short-shrifted in favor of defensive or self-aggrandizing anecdotes from grudge holders or oversharers. But Zuckoff’s approach works, not just because the form he has chosen mimics so elegantly the boisterous cacophony of a really good Altman movie, but because he lets the contradictions, reconsiderations and regrets play across his pages with no agenda other than to clarify and illuminate the up-and-down-and-up career of a brilliant, erratic film artist.

¶ Nicholas Thompson's bemused review of The Preditioneer's Game: Using the Logic of Brazen Self-Interest to See and Shape the Future leaves one wondering what Bruce Bueno de Mequita's book is doing in the Book Review.

His simulations rely on four factors: who has a stake; what each of these people wants; how much they care; and how much influence they have on others. He surveys experts on the topic, assigns numerical values to the four factors, plugs the data into a computer and waits for his software to spit out the future.

¶ Although few activities are more sheerly pointless than mountain-climbing, Holly Morris's sympathetic review of Ed Viesturs's K2: Life and Death on the World's Most Dangerous Mountain (with David Roberts) suggests a book that gives humanist heft to adventure stories.

Seven frigid, tedious days later, they crawled out of their battered tents only to have their team member Art Gilkey collapse with thrombophlebitis, instantly turning the expedition into a nightmarish rescue mission. In perilous conditions, seven strung-together (and strung-out) climbers tried to maneuver the now immobilized Gilkey across an icy slope. When one climber slipped, the other climbers, one by one, were plucked off the mountain and began careening toward oblivion. Only a spectacular ice arrest by the seventh and final climber, Pete Schoening — today regarded as the “miracle belay” — stopped the unfolding tragedy. The injured, frostbitten men regrouped and tried to set up an emergency camp. As they did, Gilkey, who was secured out of sight around an outcrop, was freakily swept away by an avalanche. Or, less plausibly, did he cut his own rope to save the rest of the team? On their desperate descent, they followed down streaks of his blood. Gilkey’s death, no doubt, had meant their survival.

Death and amputations underscore most of the lessons Viesturs gleans from these affecting expeditions: never rappel using a ski pole as an anchor, always wand your route (that is, leave a trail of sticks should a storm wipe out your tracks), never head for the summit too late in the day, never have a love affair mountainside. (So it’s 20 below and you’re looking down the gullet of mortality. Must. Stay. Focused.) Viesturs’s conservative manifesto boils down to this: Listen to your gut and take care of your comrades; getting to the summit is optional, but getting down is mandatory.

¶ Dave Itzkoff reviews Hulk Hogan's My Life Outside the Ring (with Mark Dagostino). What is the typographic counterpart to "No Comment"?

Maybe it’s a trait Hogan picked up from his VH1 reality series, “Hogan Knows Best,” but his compulsive confessing feels more like an effort to pre-empt the Us Weeklys and TMZs of the world than an authentic attempt at soul-searching.

Permalink | Portico | About this feature

Copyright (c) 2009 Pourover Press