Reviewing the Book Review

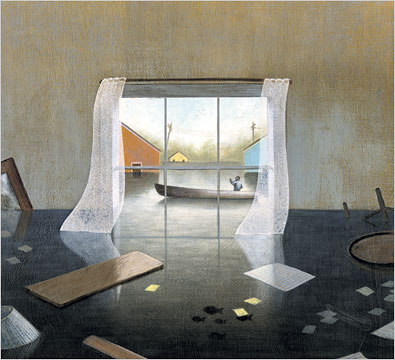

After The Deluge

16 August 2009

¶ Irresistibly, Timothy Egan devotes most of his rave review of Dave Egger's Zeitoun to storytelling the book's contents, but he wraps up on a strong (and helpful) note:

In the end, as mentioned, Zeitoun is a more powerful indictment of America’s dystopia in the Bush era than any number of well-written polemics. That is in large part because Eggers has gotten so close to his subjects, going back and forth between Syria and America, crosscutting to flesh out the family and their story.

“This book does not attempt to be an all-encompassing book about New Orleans or Hurricane Katrina,” Eggers writes in his author’s note. Of course not. But my guess is, 50 years from now, when people want to know what happened to this once-great city during a shameful episode of our history, they will still be talking about a family named Zeitoun.

¶ Erica Wagner makes a strong case for M J Hylands' novel, This Is How.

In the novel’s second part he must forge a new existence for himself. Hyland (who worked as a lawyer for several years) dispenses with cultural distractions to convincingly display how Patrick adapts himself to prison life — better than he ever adapts to life outside. Perhaps that’s not surprising. As a free man Patrick always seems troubled by a lack of explicit rules; without them, life holds a fatal confusion for him. At least in prison there are orders to follow and rules to live by.

“This Is How” is an eerie, commanding book. It is a novel about crime, though not a crime novel; it has an almost stately pace and yet it’s thrilling.

¶ Roxana Robinson's rather patronizing review of Richard Russo's new novel, That Old Cape Magic, is a tissue of storytelling that counts on readers familiar with Mr Russo's work to fill in the blanks instead of inviting new readers to the party.

Russo has written six previous novels, among them the Pulitzer Prize-winning Empire Falls, and we’ve come to expect certain things: a complicated skein of plotlines, deep connection to place, and affection for the large cast of characters who blunder and struggle through his pages. That Old Cape Magic does not disappoint.

¶ Samuel Freedman's impossible complaint about The Snakehead: An Epic Tale of the Chinatown Underworld and the American Dream is a classic of its kind: the doggedly disappointed review that has another, better book — possibly one written by the reviewer — in mind. Why the editors publish such unhelpful rubbish is beyond guessing.

Yet Keefe proves maddeningly incapable of comprehending and thus conveying any of the passengers [aboard the Golden Venture] as three-dimensional individuals. They are, like the denizens of Riis’s Lower East Side, objects on which forces act, devoid of agency and autonomy, merely problems we are expected to observe and correct. What kind of grit or desperation must these Chinese throb with to risk the stealthy voyage to America? What was it like day after day in their fetid cargo bay? What on earth did they think was going on when the ship went aground? How did they keep from losing all hope during years of captivity in the United States? We never find out, at least not from the Chinese themselves.

The absurdity of this complaint is only enhanced when Mr Freedman quotes Mr Keefe on his decision not to explore "the particulars of what happened during the months at sea."

¶ David Gates's review of Justin Cartwright's novel, To Heaven by Water is brazenly unsympathetic.

I’ll admit that “To Heaven by Water” isn’t the worst novel ever written. Its various themes play out tidily, its characters’ parallel dilemmas move expeditiously toward their predictably provisional resolutions. But it has the musty air of a merely literary exercise, without the intimacy and urgency in the face of sexuality and mortality that mark, say, the recent work of Philip Roth. It’s ponderous, but not truly serious: it’s not going to upset anybody. When it finally circles back, as you know it must, to another recitation of “The Windhover” — did all Brits of a certain age learn this thing by heart, the way Yankees used to learn “Barbara Frietchie”? — you have the feeling you’ve been nowhere at all, in company even less stimulating than your own.

¶ Jeff VanderMeer's review of Marcel Theroux's novel, Far North, is something of a muddle.

Makepeace also doesn’t need the sentimental, far-fetched rebirth motif that closes “Far North.” It’s easy to forgive Theroux, though, for succumbing to the temptation. So much has been taken from Makepeace that she’s earned some form of kindness.

Deep into this unbearably sad yet often sublime novel, Makepeace says: “Everyone expects to be at the end of something. What no one expects is to be at the end of everything.” There’s nothing left to say after that — yet Makepeace keeps going, and the reader follows her, if not hopefully then in the hope that she will win out and that her life will have meaning to someone, somewhere.

¶ The first paragraph of Max Byrd's review of John Crowley's Four Freedoms, followed by somewhat unintelligible storytelling, is not entirely unhelpful.

John Crowley is a virtuoso of metaphor, a peerless recreator of living moments, of small daily sublimities. And his latest novel, “Four Freedoms,” is in many ways his most unguarded and imaginative work. But readers expecting fantasy or science fiction — Crowley is the author of the cult fantasy series “Aegypt” — should be warned. This new book is rooted firmly in the clear, knowable past; at times, it has the grainy, kinetic authenticity of an old newsreel.

¶ A review of a book entitled Ripped: How the Wired Generation Revolutionized Music might be expected to assure us that the revolution is sufficiently "over" that a book about it will not prove to be premature. Dana Jennings does not bother with that, however. His review is more celebration than judgment, and it makes Greg Kot's book sound about the same.

Still, the most fascinating part of the book is its retelling of how the big music companies committed capitalist suicide. The executives couldn’t get their analog heads around the digital future. If industry leaders had always followed their mistrust of technology, we’d still be listening to music on 78-r.p.m. shellac, or maybe even wax cylinders.

Ripped is another case study in American industrial arrogance, an account of companies that couldn’t (or wouldn’t) learn agility. Instead of adapting to the new reality, they started calling their customers thieves.

"Industrial" arrogance? That's not reassuring.

¶ Felix Salmon's review of the latest book about The Match King: Ivar Krueger, the Financial Genius Behind a Century of Wall Street Scandals, by Frank Partnoy, is sympathetic to the conundrum facing the author. .

Is the rise and fall of Ivar Kreuger a cautionary tale, a story of what happens when ambition overreaches and maybe edges into the world of fraud? Or is it, instead, the tale of a premeditated confidence trick perpetrated by Kreuger on millions of patsies in the banking and investing worlds?

Frank Partnoy’s true-life business thriller, “The Match King,” would like to have it both ways. Partnoy, whose previous book was Infectious Greed: How Deceit and Risk Corrupted the Financial Markets, has spent years researching Kreuger’s life and times. He has a historian’s assiduous dedication to telling the truth in all its uncomfortable complexity. On the other hand, he is even more interested in telling a rip-roaring yarn of derring-do in the wild west of 1920s high finance. The problem is that the two don’t easily mesh.

¶ Robert Hanks is unforgivingly severe about Frank Huyler's novel about a doctor seeking redemption in Kashmir, Right of Thirst. (Mr Huyler is also a doctor.)

Charles himself is curiously shallow: you never get a clear sense of what it was in his marriage he feels so guilty about. His feelings on other matters are often so nuanced you can’t work them out, and for all his talk of remorse, his encounters tend to end on a note of self-justification. There’s material for comedy here, if only Huyler had spotted it. In the end, “Right of Thirst” serves as a reminder that one quality you don’t necessarily look for in a doctor is essential in a novelist: imagination.

¶ M T Anderson responds to Elizabeth Garner's novel about a strange young man in Victorian Oxford, The Ingenious Edgar Jones with what can only be called admiring disappointment.

Readers may feel disappointed that, for all the book’s auguries and dark hints, Edgar’s career has only just begun as the story ends — so we can never really assess whether he fulfills the opening promise of falling stars. It is hard not to wish Garner had given us less of Edgar’s long, slow apprenticeship and more of his remarkable flight into adulthood. The most satisfying invention in the novel, in the end, is Garner’s own transformative prose, converting science into magic and rational inquiry into the poetry of adventure. “A miracle,” she writes, is “the changing of one thing into another, or giving life to dead things” — and this she does ingeniously.

¶ Considering the importance of its topic, Richard Bessel's Germany 1945: From War to Peace gets a surprisingly brief review from Brian Ladd. (Is there something that we're not being told?)

The distinguished British historian Richard Bessel, however, understands the difference between suffering and atonement, and with “Germany 1945” he has produced a sober yet powerful account of the terrible year he calls the “hinge” of the 20th century in Europe.

¶ David Reynolds's review of The State of Jones: The Small southern County That Seceded From the Confederacy, by Sally Jenkins and John Stauffer, takes us right into an online dispute.

These issues are the subject of an Internet debate that began when Victoria Bynum, a Texas State history professor and author of the well-researched 2001 book The Free State of Jones, wrote a review on her blog, Renegade South, in which she characterized Jenkins and Stauffer’s book as a good read but inaccurate and unjustifiably politicized. Jenkins and Stauffer responded with counterevidence and claimed that Bynum had launched “turf warfare” to promote her own book. Others joined the exchange, pointing out small factual errors made by Jenkins and Stauffer, as well as the larger one that Jones County did not officially secede from the Confederacy, invalidating their book’s subtitle.

You decide.

¶ Perhaps inevitably, Mary Jo Murphy compares L Jon Wertheim's Strokes of Genius: Federer Nadal, and the Greatest Match Ever Played to John McPhee's tennis classic, Levels of the Game.

This is where the good and the great part ways. Wertheim’s book has neither the heft of history nor the force of personality to give it anything but structure in common with McPhee’s tale. “Levels of the Game,” a book of astonishing candor, allows the rivals to sum each other up. Graebner says of Ashe: “He’s an average Negro from Richmond, Virginia. There’s something about him that is swashbuckling, loose. He plays the way he thinks.” And Ashe says of Graebner: “He plays stiff, compact, Republican tennis. He’s a damned smart player, a good thinker, but not a limber and flexible thinker.” The most we get from Wertheim is Nadal on Federer: “He’s the perfect player. Perfect serve. Perfect volley. Super-perfect forehand. Perfect backhand.”

Wertheim points out that McPhee had access inconceivable today. True, but consider the protagonists. Ashe’s improbable rise in a white sport from the segregated South, the seeds of his activism sown on the Forest Hills grass, has no parallel in the Nadal-Federer narrative. There is very little interesting biography or social context in “Strokes of Genius,” but really, who needs to know more about Nadal’s fondness for PlayStation?

It would appear that this book does not merit coverage in the Book Review.

Permalink | Portico | About this feature

Copyright (c) 2009 Pourover Press