Reviewing the Book Review

Strangers in the Land

2 August 2009

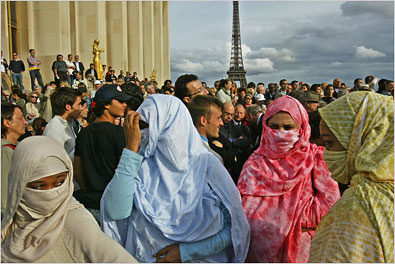

¶ Fouad Ajami, who emigrated to the United States from Lebanon forty years ago, may be forgiven for overlooking an important aspect of American history in his review of Christopher Caldwell's Reflections on the Revolution in Europe: Immigration, Islam, and the West.

“The guest is sacred, but he may not tarry,” Hans Magnus Enzensberger writes in a set of remarks that Caldwell cites with approval. Many of Europe’s “guests” have overstayed their welcome. They live on the seam: the old world of Islam is irretrievable and can no longer contain their lives; the new world of modernity is not fully theirs. They agitate against the secular civilization of the West, but they are drawn to its glamour and its success.

The United States was plagued by Nativist anxieties long before the Civil War; in some ways, it is experiencing them anew, as the prospect of a white minority approaches. But there is also a countervailing perhaps more widespread view, according to which every American is a guest. Considering Europe's demographic problems in light of American arrangements might brake the panicky note toward which this discussion inclines.

¶ Jonathan Mahler's warmly favorable review of Colum McCann's Let the Great World Spin seems to capture the flavor of the novel.

Like a great pitcher in his prime, McCann is constantly changing speeds, adopting different voices, tones and narrative styles as he shifts between story lines. Inevitably, some of his portraits work better than others. That prostitute, boldly rendered in the first person, feels disappointingly clichéd from a writer of such imaginative gifts. Far more original and nuanced are a Park Avenue housewife and her husband, the judge Solomon Soderberg, who are trying in different ways to cope with the death of their son. It is a mark of the novel’s soaring and largely fulfilled ambition that McCann just keeps rolling out new people, deftly linking each to the next, as his story moves toward its surprising and deeply affecting conclusion.

¶ Sven Birkerts writes tantalizingly about Ward Just's new novel, Exiles in the Garden.

In these pivotal scenes, Ward Just avoids what could be a hoked-up collision of opposites. Because he is a searching psychologist and a canny narrator, the consequences of the encounter become a striking instance of fate fulfilling itself. Just’s novel addresses power, but not in its deployment. Rather, “Exiles in the Garden” seeks to understand the individual’s ability — and will — to make a full self-accounting and to act accordingly. The unexamined life may not be worth living, but the unlived life, examined, yields a stark cautionary wisdom.

¶ Lawrence Downes's rather dismal review of Imperial, by William Vollman, seems hard to beat as a non-recommendation.

Having gotten back from about 40 days and 40 nights there, I can tell you: Imperial is a vast, forbidding, monotonous, sprawling place, from which Vollmann has assembled a vast, forbidding, monotonous, sprawling book.

Vollmann often seems less interested in explaining Imperial than in exposing himself — his erotic adventures and half-hearted investigations — stressing all the while that Imperial remains an ultimately unknowable place, as if to inoculate himself against accusations that he is wasting the reader’s time.

For whatever reason, in a decade exploring “the continuum between Mexico and America,” he never mastered Spanish.

Personally, I'm inclined to agree with Mr Downes; I have never been able to read an entire page of this writer's work. But at a minimum a review of such a book ought to try to explain how it came to be published.

¶ Ron Carlson's The Signal gets a review from Jennifer Gilmore that feels ambitious on the novelist's behalf.

The Signal takes us into terrain that’s stunning and terrible. In doing so, it becomes both an elegy to a broken marriage and a heart-stopping, suspenseful thriller. It’s a difficult journey, but relax: with Ron Carlson, you really are in expert hands.

¶ Mark Harris's review suggests that "Conquest of the Useless" is an unimprovable title for Werner Herzog's Fitzcarraldo diaries, but neglects to mention what such a victory might accomplish.

But the befogged internal swirl of Herzog’s mind becomes an improbably apt vantage point from which to view the history of “Fitzcarraldo.” For all his maddening opacity (“Time is tugging at me like an elephant, and the dogs are tugging at my heart”), Herzog renders a vivid portrait of himself as an artist hypnotized by his own determined imagination. Occasionally he leaves the jungle, but he never really leaves it behind. He stops in New York in December 1980, anthropologically observing the dazed mourners in Central Park after John Lennon’s death while fretting about unsigned contracts. In England, he visits the set of “The Shining” and meets Stanley Kubrick, but the two men, each trapped in his own nightmarish production, don’t really connect. Back in Peru, he gets a telegram from Munich warning that his mother may die. Someone steals his underwear. He records all this with the same benumbed neutrality. Nothing reaches him — not other people, not the punishing weather or tribal hostilities or delays, not even his notoriously loony star. (“No one will ever know what it cost me to prop him up, fill him with substance and give form to his hysteria,” Herzog writes of Kinski, concealing the full story even from his diary.)

(Conquest of the Useless: Reflections from the Making of Fitzcarraldo, translated by Krishna Winston.)

¶ To the small group of people not yet aware that

the degree to which we humans will finally stop abusing other creatures and, for that matter, one another, will ultimately be measured by the degree to which we come to understand how integral a part of us all other creatures actually are

but willing to learn, Elizabeth Royte's guardedly favorable review recommends The Wauchuila Woods Accord: Toward a New Understanding of Animals, by Charles Siebert.

¶ Peter Stevenson likes On Kindness, by Adam Phillips and Barbara Taylor, but his review is nice rather than kind.

There is a happy ending: the magical kindness of childhood can evolve into a “robust” genuine kindness if child and parent allow their relationship to endure hatred — the kind every child feels when he realizes his parent will not always be able to meet his needs, and the kind that parents may feel in return. Phillips and Taylor suggest it’s not an easy journey. Indeed, the ones who pay the largest price for our contemporary cloak-and-dagger relationship with kindness are children, whom adults fail by neglecting to help them “keep . . . faith with” kindness, and thereby sentence to a life “robbed of one of the greatest sources of human happiness.”

¶ Brenda Wineapple writes appealingly about Caroline Moorhead's new life of a talented aristocratic survivor, Dancing to the Precipice: The Life of Lucie de la Tour du Pin, Eyewitness to an Era.

Breathlessly crowded (sometimes cluttered) with event, character and sly social history (as well as a running commentary on French fashion), “Dancing to the Precipice” reveals little of its subject’s inner life. Her keen powers of observation were not turned on herself, as far as we know, and Moorehead, to her credit, is no biographical busybody. Quite the opposite. Her restraint is not unlike her subject’s, and for the most part she lets de la Tour du Pin speak for herself. She who consorted with Germaine de Staël, Talleyrand and Chateaubriand thus comes across as slightly snobbish and without a gift for introspection, but hard-working and basically decent. Well trained in the art of subterfuge, though she liked to affect the opposite, she was, in sum, a likable opportunist with remarkable staying power.

¶ Matt Bai's review of "What The Heck Are You Up To, Mr President?": Jimmy Carter, America's "Malaise," and the Speech That Should Have Changed the Country rather surprisingly makes Kevin Mattson's "incisive, fast-paced and fun to read" gloss on a slice of history sound like a must.

Mattson, a liberal historian at Ohio University, means to reclaim Carter’s legacy from the dark dungeon of presidential history, but in this he is undercut by his integrity as a storyteller. The thoughtful president who emerges in these pages is exposed, nonetheless, as a man profoundly overmatched by the job.

¶ Andrew Rice's The Teeth May Smile But the Heart Does Not Forget: Murder and Memory in Uganda gets a strongly favorable review from Howard French.

Once in a while, though, the experience of much of the continent is crystallized in the story of a single country, and when that story is told with a combination of attentiveness to historical background and genuine care for the lives of real people, the small world of serious Africa books for nonspecialists becomes enriched. With “The Teeth May Smile but the Heart Does Not Forget: Murder and Memory in Uganda,” Andrew Rice has written just such a book.

¶ Robert Frank reviews two new books about employment practices at Wal-Mart, and makes both of them — To Serve God and Wal-Mart: The Making of a Christian Free Enterprise, by Bethany Moreton; and The Retail Revolution: How Wal-Mart Created a Brave New World of Business, by nelson Lichtenstein — sound vital.

At the heart of that strategy was the company’s emphasis on the Christian concept of “servant leadership.” In other parts of the retail sector, the servitude demanded of retail clerks was typically experienced as demeaning. But by repeatedly reminding employees that the Christian servant leader cherishes opportunities to provide cheerful service to others, Moreton argues, Wal-Mart transformed servitude from a negative job characteristic into a positive one.

...

Lichtenstein, a professor of history at the University of California, Santa Barbara, also provides a detailed look at the dark side of the company’s employment practices. From its ruthless efforts at union-busting to its determination to overcome basic safety and hours regulation to its widespread employment of sweatshop subcontractors in China, Wal-Mart has consistently maintained that no one has the right to limit the corporation’s freedom to act as it pleases.

¶ Joe Meno writes warmly about Nic Brown's Hurrican Hugo novel, Floodmarkers.

Brown’s characters are the kind of small-town blue-collar workers we don’t see enough of in fiction anymore. They take care of other people’s children or drive buses or work at hot-dog factories — and in Brown’s capable hands, they have active interior lives and desires. In the middle of the storm, what they most often desire is the comfort of another person.

¶ Robin Romm seems to like Hello Goodbye, by Emily Chenowith, but she also seems to have plausibility issues of the literary persuasion.

Eventually, Abby learns that her mother’s cancer is terminal. She casts aside youthful preoccupations, as well as her virginity. Elliott must also face a kind of reckoning, as Abby’s grief forces him into new challenges of fatherhood. Only Helen is left untarnished, thinking that “the world is beautiful, and she is so glad she has seen it.” At some point, she’ll have to wrestle the truth. In fiction, though, unlike in life, one can avoid such brutal moments. Chenoweth leaves the family at the resort, intact, suggesting a kind of eternal togetherness. It’s a generous gesture — a melancholy wish. But it, too, is a fantasy waiting to be dispelled.

Permalink | Portico | About this feature

Copyright (c) 2009 Pourover Press