Reviewing the Book Review

Hush, Memory

17 May 2009

In which we have a look at this week's New York Times Book Review.

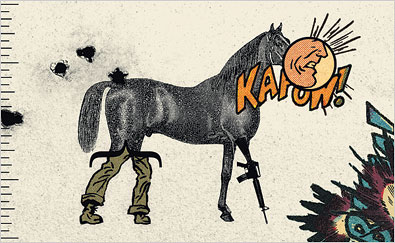

¶ Bruce Barrett's enthusiastic review of Doug Stanton's Horse Soldiers: The Extraordinary Story of a Band of US Soldiers Who Rose to Victory in Afghanistan — "a thrilling action ride of a book" — carries one important caveat:

Mitch Nelson, the Special Forces captain, takes on the role of leading man in this huge cast (a list of the book’s key players runs to more than 100 names), but the author sketches Nelson and his comrades in such bland macho superlatives that they all tend to blend into one intense, hard-as-nails G.I. Joe. And they’re all itching for a fight. A bucking helicopter ride into the combat zone wasn’t merely exciting for Nelson. “It completed Mitch,” Stanton writes. “Made him new.” When another Special Forces commander reaches a forward base near the fighting, the author writes: “He was in. Game on.” We’re galloping toward Clive Cussler territory here — and raising some unsettling echoes of a bring-it-on mind-set that, while understandable in a combat soldier, invites disaster when it percolates up to the Oval Office.

¶ David Gates warns us off the tangent of pathography in his warm review of the newly-published 1963? novel, Towards Another Summer, by the fiercely interior Janet Frame.

Like every writer worth remembering, Frame exploits — or creates on the page, to be absolutely puristic about it — her peculiar sensibility, her private window into the universal. Has anyone not felt the strain on those hawsers connecting the self to its various social impersonations? A writer’s neurochemistry may matter to physicians, biographers and general-purpose gossips, but it’s not the reader’s business. Frame’s sad, slyly comic fish-out-of-water story needs neither explanation nor excuse, and Grace’s aloneness isn’t a medical condition — it’s a human one.

¶ Why did the Book Review editors assign Reynolds Price's new memoir, Ardent Spirits: Leaving Home, Coming Back, to David Leavitt? Mr Leavitt writes kindly about the book, but a fundamental lack of sympathy cannot be concealed. Commenting on Mr Price's disinclination to write about the kind of homosexual relationships that constituted his own erotic life, Mr Leavitt writes,

I’d be dishonest if I didn’t admit that, as someone who has written extensively about these “kinds of relations,” I take as much exception to Price’s assertion that same-sex relationships are “hardly promising as fictional subjects” as to his exclusion of non-heterosexual lives from “complex families with lengthy histories.” And yet I can’t help suspecting that when Price claims that “few readers are interested, over long stretches, in stories of homosexual life,” what he’s really saying is that, as a writer, he has never been interested in stories of homosexual life. If this is the case, then his own queer story would exert far less attraction for him than, say, that of Rosacoke Mustian, the heroine of his wonderful first novel, A Long and Happy Life. Such passion as Rosacoke feels for Wesley Beavers her creator sublimated in his own youth more often than he indulged — which may be why Ardent Spirits, even as it aspires to celebrate the profligate joy of experience, succeeds mostly as a wistful meditation on roads not taken.

This is why we need more book critics who do not write novels.

¶ Tom McCarthy's review of Clancy Martin's How To Sell seems overly concerned with pigeonhole and/or marketing issues.

I found How to Sel” very enjoyable. I experienced a growing fondness for the coke-addled and increasingly amoral brothers as they rushed from gem trader to topless bar to brother’s girlfriend’s bed and back again. My pulse raced as Bobby risked his job to tell a hard-up housewife who’d come in to sell a ring that, unbeknown to her, was worth at least five grand — and for which, if Jim had his way, she’d receive no more than five hundred — to leave the store as quickly as she could and go to the honest jeweler one block away (a generic warmhearted scene, essentially the same one you get in Casablanca when Rick rigs the roulette table for the young Bulgarian couple). The novel is a good, pacey and ultimately unchallenging read. Why couldn’t they just say that on the cover? “Entertaining, zippy and unchallenging — X, author of Y.”

The reason they don’t, of course, is that, as with the whiskey-soused prospective purchaser, there’s a bigger sale being made: we’re being asked to buy into the notion that lively storytelling and more-than-adequate craftsmanship constitute great, “classic” literature. I’m not so sure. To bastardize the Latin, emptors need to sober up and exercise a little caveating over that one. I suspect that real, high-karat literature, with its complexity and ambiguity, its general slipperiness, is sitting in another box, one opening to a dimension that “How to Sell” doesn’t breach (and, to both its and its author’s credit, doesn’t itself actually claim to) — or, to use a fittingly ur-geological metaphor, that it’s lying buried in a rock-seam that this book walks comfortably over the top of but leaves unmined.

¶ It's difficult for me to write objectively about Jim Shepard's review of Luca Antara: Passages in Search of Australia, by Martin Edmond, because its first paragraph bristles with repellents, at least to me.

The porousness of generic borders isn’t exactly news, and anyone who’s read W. G. Sebald has a vivid sense of just how much can be accomplished in that hazy ground between memoir, history and speculation. Martin Edmond sallies into that same ground with Luca Antara — part memoir, part fiction and part quasi-scholarly inquiry into the history of the earliest discoverers of Australia. The author of two books of poetry and several works of nonfiction, Edmond is a New Zealander who sees Australia as both familiar and exotic. In an opening author’s note, he reminds us of Mark Twain’s remark in “Following the Equator” that Australia’s history is “so curious and strange” that it reads like “the most beautiful lies.”

The review, however, is largely sympathetic, and I hope that readers for whom Sebald, Twain & Co are not rebarbative will give reading it a thought.

¶ If you have the stomach for another book about Iraq, Robert Worth makes a strong case for Wendell Steavenson's The Weight of a Mustard Seed: The Intimate Story of an Iraqi General and His Family During Thirty Years of Tyranny.

So it’s a relief to read Wendell Steavenson’s Weight of a Mustard Seed” a masterly and elegantly told story that weaves together the Iraqi past and present. Her subject is Kamel Sachet, an Iraqi general and war hero who came to despise Hussein, and was finally executed in 1999. Steavenson, a journalist who has written for many English and American publications, set herself a difficult task: Sachet died long before she ever set foot in Iraq. The country began to implode soon after she arrived in 2003, making it even harder to piece together his life. But she succeeds, and makes his story a powerful inquiry into the moral question at the heart of Hussein’s Iraq and so many other dictatorships: Why did people go along with it? Did any resist? And if so, what made them different?

¶ Jonathan Rauch's review of Richard Posner's A Failure of Capitalism: The Crisis of '08 and the Descent Into Depression is somewhat jaw-dropping, because, if it is to be believed, the rather bloody-minded conservative Chicagoan calls for "a more active and intelligent government to keep our model of a capitalist economy from running off the rails.” Judge Posner declines, it seems, to be more specific.

By the last page, not a single lazy generalization has survived Posner’s merciless scrutiny, not one populist cliché remains standing. A Failure of Capitalism clears away whole forests of cant but leaves readers at a loss as to where to go from here. In other words, it is only a starting point — but an indispensable one.

¶ Walter Reich's impassioned review of The Third Reich at War, by Richard J Evans, insists that ethnic cleansing was not a Nazi sideshow but the main event.

If the racial reordering of Europe was the heart of the Nazi animating vision, the Holocaust was that heart’s left ventricle. Evans shows how, with the invasion of the Soviet Union, the mass murder of the Jews began. German killing squads fanned out to shoot them. One SS man who methodically murdered Jews and watched as “brains whizzed through the air” wrote: “Strange, I am completely unmoved. No pity, nothing.” Soldiers and SS men took snapshots of the executions, some of which were found in their wallets when they were killed or captured by the Red Army.

¶ Who knew?

Even the European discovery of America has a provenance in flotsam. Inspired by the drift patterns of debris in the Mediterranean, Columbus was able to plot a judicious course westward. Indeed, had he not used ocean currents to speed his journey, Ebbesmeyer argues, Columbus would most likely have had to turn back before sighting land.

Paul Greenberg gives Flotsametrics and the Floating World: How One Man's Obsession With Runaway Sneakers and Rubber Ducks Revolutionized Ocean Science, by Carl Ebbesmeyer and Eric Scigliano an interested, but not entirely favorable review.

¶ Caryn James signals the parts of David Thomson's memoir, Try to Tell the Story: A Memoir, that she found a tad wearying, but her favorable review is warm indeed.

An only child living with his mother and grandmother, he invented a teasing older sister named Sally. The imaginary sibling; the buildings bombed out from the war; the elusive father, whom he adored and resented: none of that is terribly surprising. But Thomson’s pellucid writing and flashes of insight make his memories unpredictable and rewarding.

¶ Helene Cooper gives This Child Will Be Great: Memoir of a Remarkable Life by Africa's First Woman President, by Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, a generally favorable review.

This Child Will Be Great will most likely not appeal to everyone. Johnson Sirleaf, whom I have interviewed, refrains from the sort of emotional detail that might allow her life’s story to resonate with readers uninterested in the “who’s up, who’s down” scales of Liberian political parties. She throws a lot of abbreviations out there, and even Liberians may have trouble with some of them.

¶ There's a lot of storytelling in Caroline Elkins's review of Chris Cleave's Little Bee, but a strong favorable judgment does much to compensate.

While the pretext of Little Bee initially seems contrived — two strangers, a British woman and a Nigerian girl, meet on a lonely African beach and become inextricably bound through the horror imprinted on their encounter — its impact is hardly shallow. Rather than focusing on postcolonial guilt or African angst, Cleave uses his emotionally charged narrative to challenge his readers’ conceptions of civility, of ethical choice.

For what it's worth, a very brief but far more engaging response to Little Bee appears at The Second Pass.

¶ Tom Barbash's review of Howard Jacobson's The Act of Love is ultimately incoherent: is this a funny book, good for a laugh, or just an odd one, full of twisted erotics?

Jacobson goes to great comedic lengths to detail Felix’s love for his wife, including soaring tributes to her breasts and dancing style and general beauty, from which he “had to look away. It was either that or go blind.” The book is also stocked with aphorisms about marriage and attraction, deviancy and love. For Felix, jealousy and love are so closely intertwined he can’t tell them apart. Above all, he fears the loss of jealousy; he’s as protective of it as a doting father might be of a favorite child.

¶ Having devoted the bulk of her too-short review of A Sandhills Ballad to storytelling, Julia Scheeres winds up by dismissing Ladette Randolph's prose.

Despite its emotional resonance, Randolph’s storytelling can be heavy-handed. Consider, for example, the symbolically overfreighted names she has chosen for her central characters. Or the way Mary reveals a rebellious inner life by banging out atonal chords on the piano when she thinks no one’s around. But the idea that a depressed one-legged preacher’s wife with four small children would catch the eye of a worldly-wise photographer requires too great a leap of faith. Excuse me for not believing in such miracles.

File this classic of its kind with the reviews that ought to have been rejected by the editors.

¶ Jincy Willett's review of Sarah Dunn's Secrets to Happiness is fresh and intriguing.

In the end, what makes Dunn’s novel such a pleasure to read is the very thing that keeps it from being a breathless page-turner: Holly’s singular spirituality. She may be as baffled as everyone else about how to achieve happiness, but she also knows that happiness isn’t all it’s cracked up to be. In a world — fictional and non- — where doing a good thing gets you accused of having a messiah complex, and doing whatever you want is justified as following your path, Holly never stops trying to figure out where her duty lies. Underneath it all — the sex, the shopping, the city — she’s an old-fashioned heroine. Also funny.

Permalink | Portico | About this feature

Copyright (c) 2009 Pourover Press