Reviewing the Book Review

On the Beach

22 February 2009

In which we have a look at this week's New York Times Book Review.

In the center of this week's issue, there's an essay, "The Great(ness) Game" by David Orr, on the state of American poetry today with particular relation to the idea of greatness.

What will we do when Ashbery and his generation are gone? Because for the first time since the early 19th century, American poetry may be about to run out of greatness.

Mr Orr never quite states that "greatness" implies something like "fewness," but he comes close enough:

When we lose sight of greatness, we cease being hard on ourselves and on one another; we begin to think of real criticism as being “mean” rather than as evidence of poetry’s health; we stop assuming that poems should be interesting to other people and begin thinking of them as being obliged only to interest our friends — and finally, not even that. Perhaps most disturbing, we stop making demands on the few artists capable of practicing the art at its highest levels. Instead, we cling to the ground in those artists’ shadows — John Ashbery’s is enormous at this point — and talk about how rich the darkness is and how lovely it is to be a mushroom. This doesn’t help anyone. What we should be doing is asking why a poet as gifted as Ashbery has written so many poems that are boring or repetitive (or both), because such questions will allow us to better understand the poems he has written that are moving and funny and beautiful. Such questions might even allow other poets — especially younger poets — to find their own ways of writing poems that are moving and funny and beautiful. Which for those of us who read them, for those of us who believe in them, would be a very great thing indeed.

Is the concept of discrimination safe for the world yet?

FACT

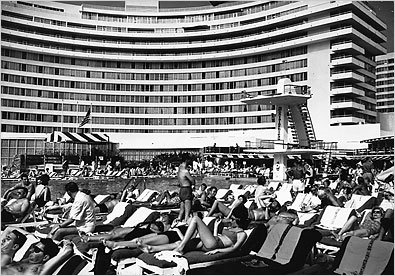

¶ Carl Hiaasen's enthusiastic review of Steven Gaines's Fool's Paradise: Players, Poseurs, and the Culture of Excess in South Beach doesn't quite persuade me that this book about Miami Beach is a thoughtful consideration of vernacular fantasy; it sounds more like the backstory to Miami Vice.

As in Philistines at the Hedgerow, his wry dissection of the Hamptons, Gaines sees symptoms of social dysfunction in architecture, like the garishly emblematic Fontainebleau Hotel on Collins Avenue. It was the product of a tumultuous collaboration between an obstinant developer named Ben Novack and the architect Morris Lapidus. The two couldn’t stand each other, and went to their respective deathbeds claiming sole credit for the design of the massive, weirdly curved structure, which was built in less than a year.

Maligned by critics, the Fontainebleau instantly became a lively hangout for card sharks, mobsters and movie idols. Frank Sinatra performed there regularly for 20 years — free, according to Gaines — and in return got unlimited use of a penthouse suite. Gaines asserts, “The only thing Sinatra paid for was his hookers.” Well, at least he didn’t forget the little people.

¶ Jason Goodwin raves convincingly about The Bloody White Baron: The Extraordinary Story of the Russian Nobleman Who Became the Last Khan of Mongolia, a book about the nasty aftermath of the Russian Revolution.

Palmer, a travel writer who lives in Beijing, gives us a brilliant portrait of a very nasty war, fought by horrible people in a hostile environment. As he points out, the final capture and execution of Ungern in 1921 was a sideshow, and the chaos of Russia’s far east was not overcome by the defeat of the Whites. The Communists had only just got going, and were to massacre their own people by the millions in the coming years. The Japanese atrocities in China were a mere decade away. Ungern’s contempt for human life, his icy hatred of Jews, his appeal to a monstrous, ill-formed mysticism foreshadowed the foundations of the Third Reich. What makes “The Bloody White Baron” so exceptional is Palmer’s lucid scholarship, his ability to make perfect sense of the maelstrom of a forgotten war. This is a brilliant book, and I’m already looking forward to his next.

¶ One might with that Leslie Garis's account of A Hidden Life: A Memoir of August 1969 were more straightforward, but she seems quite literally fascinated by Johanna Reiss's story, which includes hiding from the Nazis in Holland to losing a husband to suicide. The result is to make the book sound almost unpublishably private.

Reiss handles this difficult material by probing her memory for clues, putting facts and suppositions together in feverish prose, jumping back and forth in time (“Have you forgotten what sounds can do? Draw attention to people who’ll come and kill. Sshht, your little girls are only a few walls away”), driven by feelings so intense that at times it seems she is tripping on her mind’s own acid. This searing journey reads like the author’s desperate last chance to discover Jim’s secret self.

¶ Like other reviewers, Walter Kirn faults David Denby for never providing a firm definition of the term under review in his Snark: A Polemic in Seven Fits. But if "snark" means "smiling but dismissive condescension about the alleged missteps of older, somewhat authoritative people," then Mr Kirn's review meets the description.

A portion of Denby’s diatribe against the leveling impulse behind much humor now (a now when the high and mighty aren’t leveled enough, but stroll around freely on Manhattan streets wearing widows’ lost pension money as jewelry) consists of a series of chapters about the past whose cutesy archaic Dickensian titles display all too clearly what Denby has to fear from the off-the-cuff jokers of the Facebook age. Exhibit A: “A Brief, Highly Intermittent History of Snark, Part 2, in which the author brings his search almost to the present era, celebrating and deploring certain publications and exposing the snarky tendencies of a famous author.”

There is no attempt to engage with Mr Denby's complaint, which at one point is characterized as "moronic."

¶ Jedediah Purdy's review of William Goetzmann's Beyond the Revolution: a History of American Thought From Paine to Pragmatism is lucid as well as timely.

Goetzmann proposes to unify his book with a theory of civilization as a dispersed information-processing system, in which every mind plays a part and intellectuals are the integrating circuits. Perhaps prudently, he does not develop the idea. Rather, it is a metaphoric clue to Goetzmann’s intellectual temper. He is basically a Hegelian, who believes that national (and world) history has an intellectual logic distributed among its disparate parts, whose unity one can see in hindsight. While not a fashionable perspective, this has distinct merits, among them that it satisfies the human appetite for an intelligible story. His book, rich in strange detail and vivid speculation, aspires to universal history. It is a fox dreaming of hedgehogs. So is the America it describes.

Indeed, this is an apt book for the opening of the Obama administration. The Declaration of Independence is Obama’s touchstone, as it was Lincoln’s, because it anchors the country to a cosmopolitan vision of openness and equality. It has never been clearer that the country’s best self is a global inheritance, its worst a parochial self-certainty. A book of 19th-century ideas that portrays America as one part Google, one part melting pot and one part utopian dream may just have found its moment at the inauguration, eight years late, of the 21st century.

Timely, in other words, but not too timely.

¶ Kevin Baker argues persuasively that Beverly Gage's The Day Wall Street Exploded: A Story of American in Its First Age of Terror, although centered on the terrorist attack on the Morgan Bank in September, 1920, provides a much-needed reminder of this country's history of "industrial warfare."

Even though the crime was never solved, it had other repercussions. The bungled investigation and its wholesale violation of people’s civil liberties, as Gage shows, led to a major housecleaning at the Bureau — which, paradoxically, enabled the rise of the biggest civil liberties violator in American history, J. Edgar Hoover. And the bombing contributed to an atmosphere in which two other anarchists, Sacco and Vanzetti, were convicted of murder in a case that would become the great leftist cause of the decade.

¶ Thomas Mallon's admiration for Tom Baum's Nine Lives: Death and Life in New Orleans is articulate and infectious.

Even though the crime was never solved, it had other repercussions. The bungled investigation and its wholesale violation of people’s civil liberties, as Gage shows, led to a major housecleaning at the Bureau — which, paradoxically, enabled the rise of the biggest civil liberties violator in American history, J. Edgar Hoover. And the bombing contributed to an atmosphere in which two other anarchists, Sacco and Vanzetti, were convicted of murder in a case that would become the great leftist cause of the decade. e

¶ On the basis of Polly Morrice's guardedly favorable review of America Anonymous: Eight Addicts in Search of a Life, by Benoit Denizet-Lewis, I should say that the book ought to have been covered in the newspaper's Health section.

To organize his narrative, Denizet-Lewis focuses on his mostly pseudonymous subjects in alternating chapters. This novelistic technique injects suspense (will Kate stop stealing from Target?) and highlights the sadness of addicts’ lives, but it doesn’t make us care about everyone profiled.

¶ Tobin Harshaw is amused by but slightly impatient with Justin Marozzi's The Way of Herodotus: Travels With the Man Who Invented History; only at the end of a too-short review does he welcome tha author's digressions from the first historian's path.

Then to Greece, where instead of mooning about the touristified battle sites of Thermopylae and Marathon, Marozzi lays waste to a three-day conference of pretentious academics. (Oh, how Herodotus — “part learned scholar, part tabloid hack, but always broad-minded, humorous and generous-hearted” in Marozzi’s words — would have snickered at the conceits of postmodernism.) And then — digression of all wonderful digressions — he finagles dinner at the Peloponnesian villa of the legendary British travel writer and World War II hero Sir Patrick Leigh Fermor, in his 10th decade but still full of retsina and vinegar.

¶ Another travel book, retracing journeys rather more recent, is Rory McLean's The Magic Bus: On the Hippie Trail From Istanbul to India, and Jane and Michael Stern are clear about why they like it.

Good or bad, were they really so significant? MacLean thinks so. He lectures a group of young travelers that the beats and hippies “brought minority rights, ecology and alternative medicine into the mainstream” and “for a few short years tied together the world.” Whether such grandiose claims are true or just an expression of the baby-boomers’ self-importance, there’s no denying that the stoned rovers were present at the beginning of a cataclysmic period in history, whose legacy “Magic Bus” describes in exquisite detail, most of it sorrowful.

POETRY & FICTION

¶ Joel Brouwer's warmly favorable review of Miller Williams's Time and the Tilting Earth: Poems is makes an intelligible case for adding this book to one's library.

Williams was a biology teacher before he ever got a job teaching poetry, and many of the poems here set up brawls between verifiable science and religious faith. This is dangerous material for poetry, since, as Williams himself once wrote in an essay, “a thing may fail as a poem because it tries to do what a poem cannot do: it tries to become a treatise on cosmic truth. . . . We can best be exact about the cosmic things — God and truth, beauty, eternity and love — by not talking directly about them.”

Williams consistently fails to take his own advice in his new poems, yet most of them succeed regardless.

¶ Roxana Robinson has a fine old time storytelling her way through a review of The Good Parents, by Joan London. Sadly, there is no evidence, for all the chatter, of the author's "rippling, exquisite prose." Instead, we're presented with a cast of unattractive men and dependent women.

Cy is a gangster, and Toni (during the liberated ’60s) becomes a kept woman. It’s a curious notion: why would a woman abandon the idea of keeping herself? What’s the appeal of subservience? Where’s the symmetry in this bargain? Cy and Maynard are interested mainly in sex, but also in ownership. Toni and Maya are interested mainly in affection, but also in ownership. Each side believes the other holds more power; this secret certainty arouses a stirring of illicit desire. For both, there’s something voluptuous and exciting about relinquishment, some dark pleasure to be had from it.

¶ James Wilcox clearly likes Marisha Chamberlain's The Rose Variations, but the short space allotted can barely accommodate his storytelling and has no room for his judgment. As so often with such reviews, the novel comes off looking merely peculiar.

Permalink | Portico | About this feature

Copyright (c) 2009 Pourover Press