Black Mischief: a reading

¶ Chapter One

Quite aside from its other charms, Black Mischief will delight readers to whom political correctness has become burdensome. Although a converted Roman Catholic, Waugh embraced contemptuous racial bigotry with pagan abandon. In fairness, it ought to be pointed out that he had contempt for almost everyone on earth; but he was always happy to make use of stereotypes if it would get a laugh. Embarrassingly, it usually still does, at least in the context of his monstrous farces. One little nugget will suffice: the Oxford-educated heir to an African empire whose throne, for the moment, is anything but secure, finds himself abandoned in a fortress.

Night and the fear of darkness. In his room at the top of the old fort Seth lay awake and alone, his eyes wild with the inherited terror of the jungle, desperate with the acquired loneliness of civilisation.

And that's a fairly mild example. The "inherited terror" is meant quite seriously; Waugh believed in a kind of debased Darwinism, according to which we are who we were. If our ancestors responded to the nocturnal crashings-about of predators with exophthalmic anxiety, then so will we. Waugh is kind enough to allow Oxford to make its contribution to the Emperor's discomfort.

Black Mischief takes place on an imaginary island in the Indian Ocean, not far from either Somalia or Aden, formerly known as Sakuyu, but now the Empire of Azania. (We will address this name separately.) Azania is not as large as Madagascar from the look of it, but it's a big island, home to numerous tribes and ethnic groups, among them, the native "anthrophagous" Sakuyu people. African immigrant tribes inhabit the north, while Arab merchants hold the southern coast. Formerly a bustling hub of the slave trade, their city of Matodi has become a sleepy, derelict town, while the capital, erected by Seth's grandfather, the first Emperor, sits high in the hills; one suspects its name, Debra-Dowa, to reflect some sort of Mitford joke. The Emperor left a daughter, who was married to an unenthusiastic Arab of such pedigree that his fathers "would not have ridden a horse with so obscure a pedigree" as the princess. Their offspring, Seth, has just returned from Oxford, upon his mother's death, to claim his throne, and to find the country in an uproar. The exposition takes about ten pages, and is saturated with contempt for the empty grandiosity of colonial "improvement" (not, note, that Azania is anybody's colony).

Desertion is the opening note. Seth, dictating proclamations to his secretary, Ali, is interrupted by the sight of the last departing boat.

"Is there still no news from the hills?"

"None of unquestionable veracity, your majesty."

"I gave orders that the wireless was to be mended. Where is Marx? I told him to see to it."

"He evacuated the town late yesterday evening."

"He evacuated the town?"

"In your majesty's motor boat. There was a large company of them - the station master, the chief of police, the Armenian Archbishop, the Editor of the Azanian Courier, the American vice-consul. All the most distinguished gentlemen in Matodi."

"I wonder you weren't with them yourself, Ali."

"There was not room. I supposed that with so many distinguished gentlemen there was a danger of submersion."

I quote all of this to convey the fact that the dialogue, as well as the atmosphere, of the opening chapter of Black Mischief is Gilbert & Sullivan - with knives. Nobody is to be trusted; later on, Ali will try to persuade Seth to trust him "as a traitor." Wisely, Seth does not, but it is anybody's guess until the dust settled just who's going to be found without a seat when the music stops.

The distinguished gentlemen have been "evacuating the town" because the rebel forces, under somebody called Seyid, seem bound to vanquish the ragtag forces fighting in Seth's name. The hills behind Matodi are alive with the buzz and rumble of an approaching horde, which is why the good men of Matodi have been secreting their valuables. Poor Mr Youkoumian, a merchant of parts, is trying to make a deal with somebody to pay for passage on a speedboat that he has pilfered; the air of double-dealing would be bewildering if it weren't so comical. Matodi braces for The End, and we're snickering. The writing is deadpan and even a trifle frightening now and then - so much so that I daresay Graham Greene might have learned a thing or two from it.

Another dawn. With slow feet Mr Youkoumian trudged into Matodi. There was no one about in the streets. All who could, had left the city during the darkness; those who remained lurked behind barred doors and barricaded windows; from the cracks of shutters and through keyholes a few curious eyes observed the weary little figure dragging down the lane to the Amurath Café and Universal Stores.

But this is not Graham Greene, and Waugh proceeds directly to this:

Mme Youkoumian lay across the bedroom doorstep. During the night she had bitten though the gag and rolled some yards across the floor; that far her strength had taken her. Then, too exhausted to cry out or wrestle any further with the ropes that bound her, she had lapsed into intermittent coma, disturbed by nightmares, acute spasms of cramp and the scampering of rats on the earthen floor. In the green and silver light of dawn, this bruised, swollen and dusty figure presented a spectacle radically repugnant to Mr Youkoumian's most sensitive feelings.

It was, after all, he who asked the soldiers whom he was unwise enough to trust to tie the woman up.

When the armies arrive in Matodi, they turn out to be the Emperors, not the rebel's. Led by General Connolly, an Irishman with "varied service in the Black and Tans, the South African Police and the Kenya Game Reserves," the victorious forces elicit magisterial contempt for the author that I shall forego quoting here. Once General Connolly has had a bath and spruced himself up, he makes his way to the fort, to see if his emperor is still around. Along the way, he encounters

a vast Canadian priest with a white habit and sunhat and spreading crimson beard who was at the moment occupied in shaking almost to death the brigade sergeant-major of the Imperial Guard.

This unnamed padre is the soul of Christianity itself.

And mind you keep your miserable savages from my mission or they'll know the reason why.

The General at last finds the Emperor "lying across the camp bed in spotted silk pyjamas recently purchased in the Place Vendôme." Seth pretends not to be at all surprised by the glorious outcome, but Connolly insists on recounting the final maneuvers, most of which were propaganda offensives. Finally, Connolly must inform Seth of the ghastly end of Seyid, the rebel leader, and he does so with deep regret, because he could not save Seyid from the "anthropophagous" troops, and Seyid was - why didn't we guess - Seth's father?

Black Mischief is the third of Waugh's novels, and a jewel in the crown of five satires with which he began his career. (Only one later novel, The Loved One, would approach these for poisoned-pen acuity.) In many ways, Black Mischief was more shocking, in its content, when it was new than, for its language, it is now, for its author never tires of debunking the prize myth of modern Europe: the viability of à la carte progress. Sidestepping the more arduous developmental path that Europe itself had followed, modernizers believed that a railroad here and a factory there would inevitably seed truly modern culture everywhere. (It is a belief that still holds neoconservatives in thrall.) Even without outside sponsorship, China and the Soviet Union would sink fortunes into redundant steel mills simply because a modern country without lots of steel mills was unthinkable. Whether from pessimism or deep humanism, Waugh understood the flimsiness of such embroidered tokens of modernity, and he devotes a few loving paragraphs to the murderous construction and subsequent sluggish decline of the Grand Chemin de Fer Impérial d'Azanie. As far as he was concerned, if civilization had not quite taken hold in England, it had no business "educating" exotic rulers, who, as Seth shows throughout the opening chapter, will learn nothing of any use at its univesities. Black Mischief begins with the following rearranging-the-deck-chairs proclamation:

We, Seth, Emperor of Azania, Chief of the Chiefs of Sakuyu, Lord of Wanda and Tyrant of the Seas, Bachelor of the Arts of Oxford University...

It's funny, but it's not just funny.

¶ Chapter Two

Chapter Two of Black Mischief, considerably shorter than the first, takes us from the wilds of Azania deep into Waugh country. If Waugh is generous with his contempt for foreigners, it's hard to describe his feeling about the English. They're certainly very dangerous.

We are at the British embassy compound in Debra-Dowa. William and Prudence are dallying in the sunshine, exchanging desperately icy stabs at wit.

"Oh, dear, men are hard to keep amused." Prudence sat up and lit a cigarette. "I think your effeminate and undersexed," she said, "and I hate you."

"That's because you're too young to arouse serious emotion."

As indeed she is, still in her teens. Presently William and Prudence get back on their mule and head back to the Legation. Meanwhile, Waugh takes us on a tour d'horizon of the diplomatic establishment at Debra-Dowa. In addition to His Britannic Majesty's minister, there is the American Mr Schonbaum, whose interesting career the author traces, and the French M Ballon, about whom Waugh says no more than that he is a Freemason. Thus the stage is set for the presentation of one of Waugh's monumental incompetents, Sir Samson Courtenay.

As a very young man he had had great things predicted of him. He had passed his examinations with a series of papers of outstanding brilliance; he had powerful family connexions in the Foreign Office; but almost from the outset of his career it became apparent that he would disappoint expectations.

Sir Samson's problem - of which he is sublimely unaware - is an inability to pay attention to the things that matter. This, working with an inbred aristocrat's very peculiar priorities, renders Sir Samson deliciously oblivious of current events. The Azanian revolution is a frightful bore because it interrupts the delivery of dipolomatic pouches bearing Lady Courtenay's bulbs. It is impossible to contact the Ambassador after dinner because, since he must have some time to himself, he has the telephone disconnected in the evening. Long before the following passages takes us up to the close of the chapter, we begin to doubt those wonderful predictions and outstanding papers.

Prudence and William had left an inflated india-rubber sea-serpent behind them in the bath-room. Sir Samson sat in the warm water engrossed with it. He switched it down the water and caught it in his toes; he made waves for it; he blew it along; he sat on it and let it shoot up suddenly to the surface between his thighs; he squeezed some of the air out of it and made bubbles. Chance treats of this kind made or marred the happiness of the Envoy's day. Soon he was rapt in daydream about the Pleistocene age, where among mists and vast, unpeopled crags, schools of deep-sea monsters splashed and sported; oh, happy fifth day of creation, though the Envoy Extraordinary, oh, radiant infant sun, newly weaned from the breasts of darkness, oh, rich steams of the soggy continents, oh, jolly whales and sea-serpents frisking in new brine...Knocks at the door, William's voice outside.

"Walker's just ridden over, sir. Can you see him?"

Crude disillusionment.

"Chance treats" is one of those Waughian phrases that can set one laughing, quite hysterically if one is in the right state of susceptibility. Its precious delicacy is as out of place as Sir Samson is in a bathtub with a play toy, or, for that matter, in a Legation at all.

After the Envoy and his household - which includes William Bland, the honorary attaché - have been introduced, we learn something of the British contingent at Debra-Dowa, which is "small and rather shady." An amusing story about General Connolly's consort concludes: "After that Connolly was not asked even to Christmas luncheon." There is, however, a Bishop, whom William and Prudence discover at the table when they return from their ride.

The Bishop, all a-twitter, wants news of the war, but the Envoy can barely detach his attention from the tinned asparagus that he's tired of eating. But now that he thinks of it, some cables have come in recently. When he asks William what they cables conveyed, William's reply is very swell. "I can't really say, sir. The truth is we've lost the cypher book again." William is indignant with Prudence later, but the mild lashing evidently inspires him to find the cypher book, in his collar drawer. But he can't find "Kt to QR3 CH" among the codes... The Legation gossip, stunning in its clueless banality, is abruptly followed by a short passage describing tribal violence to the south, where women from "cave villages of incalculable antiquity" steal out to rob the dead.

In the evening there is a clumsy game of bridge while Prudence plays records for Williams and Sir Samson - knits a sweater. (William asks Prudence to play "Sex Appeal Sarah," and this is a Mitford joke, which will be explained to you when you read Hons and Rebels.) Meanwhile, the French minister, convinced of imminent massacres, has obtained a report of doings at the Legation, and he is terribly mystified by "Kt to QR3 CH," which, at the risk of condescending to my readership, is a move in chess.

The next morning, Prudence tries to continue with the book that she's writing, Panorama of Life. That's silly enough in itself, but Waugh makes the most of the detail by laying out the way in which uncertain writers edit and re-edit what they're written instead of forging on.

Sex, she wrote in round, irregular characters, is the crying out of the Soul for Completion. Presently she inserted 'of man'; changed it to 'manhood' and substituted 'humanity.' Then she took a new sheet of paper and copied out the whole sentence.

This brings us to Sir Samson in the bathtub. The "Walker" who has ridden over is the American secretary, and he has news from Matodi.

"Of course we haven't got any full details yet."

"Of course not. Still the war's over, William tells me, and I, for one, am glad. It's been on too long. Very upsetting to everything. Let me see, which of them won it?"

"Seth"

"Ah, yes, to be sure. Seth. I'm very glad. He was ... now let me see .... which was he?"

"He's the old Empress's son."

"Yes, yes, now I've got him. And the Empress, what's become of her?"

"She died last year."

"I'm glad. It's very disagreeable for an old lady of her age to get involved in all these disturbances."

The chapter ends with a final dressing of irony.

At the French Legation, also, news of Seth's victory had arrived. "Ah," said M Ballon, "so the English and the Italians have triumphed. But the game is not over yet. Old Ballon is not outwitted yet. There is a trick or two still to be won. Sir Samson must look to his laurels."

While at that moment the Envoy was saying: "Of course, it's all a question of the altitude. I've not heard of anyone growing asparagus up here but I can't see why it shouldn't do. We get the most delicious green peas.

In the next chapter, we'll finally meet our hero, Basil Seal.

¶ Chapter Three

Two days later news of the battle of Ukaka was published in Europe. It made very little impression on the million or so Londoners who glanced down the columns of their papers that evening.

Thus Waugh takes us to London, the setting of Chapter Three. We overhear a broad spectrum of dismissive remarks. Then we're told that, "late in the afternoon," one Basil Seal reads the story at his club, which he has visited with the express purpose of cashing a bad check. Right at the start, Waugh calls into serious question Basil's status as a gentleman - the only status that really mattered to a man of Waugh's time and place. There is not a word in this chapter that is not complicit in Waugh's remarkable strategy of conducting his satire by means of elision and omission. In lieu of pontification, Waugh administers his critique in deadpan shocks that seem to acknowledge no system of morality whatever. The less-than-careful reader will conclude that the author is a nihilist, and it is this, rather than the occasional naughty situations, that gives Waugh's early novels their atmosphere of deep scandal. Never saying an untoward thing while making it impossible for the reader not to draw untoward inferences, Waugh titillates in the finest English going. The portrayal of Basil Seal embodies the technique. Basil can hardly open his mouth except to cadge money or expound his theories, and his conduct seems to consist largely of things left undone. Consider:

For the last four days Basil had been on a racket. He had woken up an hour ago on the sofa of a totally strange flat. There was a gramophone playing. A lady in a dressing jacket sat in an armchair by the gas fire, eating sardines from the tin with a shoe horn. An unknown man shirtsleeves was shaving, the glass propped on the chimney-piece.

The man had said: "Now you're awake you'd better go."

The woman: "Quite thought you were dead."

Basil: "I can't think why I'm here."

"I can't think why you don't go."

"Isn't London hell?"

"Did I have a hat?"

"That's what caused half the trouble."

"What trouble."

We're not told, of course, what the trouble was; it can't have been as serious as we're led to believe by this laconic exchange. The little scene has a decidedly Looking-Glass quality to it - how does one eat sardines with a shoe horn? (As to Basil's "racket," however, we will learn that it has effected the ruin of his parliamentary career.)

Although capable of waking up in strange flats after diluvian binges, Basil does take an interest in Affairs. At the club, he irritates an senior member with needling observations about developments in Azania. Then he pushes off to Mayfair for a cocktail party at Lady Metroland's, where he would be unwelcome even if he weren't dirty and unshaven. He's looking for his sister, Barbara Sothill, to hit her up for funds. Girls chatter about him, intrigued by his impossible behavior.

Once, when Basil had been a young man of promise, Lord Monomark had considered taking him up and invited him for a cruise in the Mediterranean. Basil at first refused and then, after they had sailed, announced by wireless his intention of joining the yacht at Barcelona; Lord Monomark's party had waited there for two sultry days without hearing news and then sailed without him. When they next met in london Basil explained rather inadequately that he had found at the last minute he couldn't manage it after all. Countless incidents of this kind had contributed to Basil's present depreciated popularity.

Lord Monomark, readers of Vile Bodies will remember, is a great press lord, and, seeing him at Margot Metroland's, Basil has an idea. He proposes that Monomark send him as correspondent to Azania. Monomark is elusive, but as we are beginning to learn, Basil's self-assurance is boundless, and he has only to think that something ought to be the case to begin acting as though it were. His attempt to hit up Barbara having failed, Basil turns to his mother. He arrives at her house to find that his place at the dinner table has been usurped by a more reliable guest. This means that he has to find something to do until he can catch her at bedtime. He rings up his friends the Trumpingtons and heads over to their place, where the proceedings would appall Lady Seal. Alistair and Sonia Digby-Vaine-Trumpington

lay in a vast, low bed, with a backgammon board between them. Each had a separate telephone, on the tables at the side, and by the telephone a goblet of 'black velvet.' A bull terrier and a chow flirted on their feet. There were other people in the room, one playing the gramophone, one reading, one trying Sonia's face things at the dressing table. Sonia said, "It's such a waste not going out after dark. We have to stay in all day because of the duns."

This is basically the "unknown flat" all over again, only more posh, and with Basil known to his hosts. After dinner (on the bed) and a game of "Happy Families" (our "Go, Fish"), Basil returns to his mother's.

Lady Seal is introduced as a careful, respectable widow, who gives four or five meticulously planned dinner parties a year. Waugh makes her preparations sound exhausting, but looked at closely they are only the anxieties of a pampered woman. When we actually meet her, after her dinner party, she has asked one of her guests, Sir Joseph Mannering, to stay on; she wants to talk to him about Basil. Sir Joseph "was a self-assured old booby who in the easy and dignified role of family friend was invoked to aggravate most of the awkward situations that occurred in the lives of his circle." Lady Seal's tale of woe is given in tiny, suggestive bites that once again invite the reader's imagination to fill in the details of Basil's depravity. Sir Joseph is suitably concerned by the weight of his friend's burden, but he has no doubt that he can relieve it. "Send him round as soon as you get into touch with him. I'll take him to the club." As if the Basil we've gotten to know in a few pages would take advice from an old booby!

For nearly half an hour they planned Basil's future, punctually rewarding each stage of his moral recuperation. Presently Lady Seal said: "Oh, Jo, what a help you are. I don't know what I should do without you."

The point of all this, of course, is to intensify Lady Seal's disappointment when, at her dressing table, she does see Basil, "so unlike the barrister of her dream that it required an effort to recognize him." She refuses to listen to his long and earnest pleas for several hundred pounds, but sends him to bed with instructions to call on Sir Joseph in the morning. Close readers will be anxious about a certain bauble on the dressing table.

Instead of going to bed, the inexhaustible Basil telephones and then visits his political patron and erstwhile love, Angela Lyne. Waugh is quite sly about their having sex - "And later, as they lay on their backs smoking, her foot just touching his under the sheets..." - but the adult reader is left in no doubt about what's what. Tired of hearing about Azania, and bored with Basil's fondness for rackets generally, Angela decides to give him the money that he asks for, as it will get him out of her hair. The London portion of the chapter appears to close thus:

At eleven o'clock a box of flowers from Sir Joseph Mannering and at twelve Lady Seal attended a committee meeting; it was four days before she discovered the loss of her emerald bracelet and by that time Basil was on the sea.

He has flown to Marseille - an adventurous progress in four stations ("Croydon, le Bourget, Lyons, Marseilles") - and bribed his way aboard a French colonial liner. Waugh delivers several paragraphs of vivid travel writing (including a minor racket at Port Said). "Basil turned out the light and lay happily smoking in the darkness." This is the first happiness that we've heard about. That his happiness might really consist in having left London behind is suggested by a particularly brainless conversation at yet another party at Lady Metroland's.

At Matodi, the Azanian port, Basil has a conversation with the purser before going ashore. The purser asks if Basil is visiting Azania on business. "But for once Basil was disinclined to be instructive. 'Purely for pleasure,' he said." And then he's off, in a cloud of stolen toiletries.

Chapters Four and Five

It is no small measure of Waugh's ability to entertain that he can put off triggering his plot until the second half of Black Mischief. In Chapter Four, the final bits of setup are completed. Basil secures a seat on the train from Matodi to Debra-Dowa thanks to the willingness of Krikor Youkoumian to put his wife at mortal risk to make a buck. The train is to be a special train - the victorious Emperor is on board. This does not assure a prompt departure. "The Emperor has given no orders for a delay" must surely be one of the more bottomless wells of humor. After further displays of Azanian incompetence, the train proceeds to the capital, and, after an interlude at the Legations, the novel proceeds to the Victory Ball, at Prince Fyodor's night club, Perroquet. The ball, of course, is a perfect rout, Le tout Debra Dowa shows up, only to be poisoned by Prince Fyodor's bathtub champagne and ridiculed by the author. Basil is there, too, at General Conolly's table.

The Emperor had signified his intention of making an appearance some time during the evening. At the end of the ball-room a box had been improvised for him with bunting, pots of palm, and gilt cardboard. Soon after midnight he came. At a sign from Prince Fyodor the band stopped in the middle of the tune and struck up the national anthem. The dancing couples scuttled to the side of the ball-room; the guests at supper rose awkwardly to their feet, pushing their tables forward with a rattle of knives and glasses; there was a furtive self-conscious straightening of ties and removing of paper caps. Sir Samson Courteney alone absentmindedly retained his false nose. The royal entourage in frogged uniforms advanced down the polished floor; in their center, half a pace ahead, looking neither to right nor left, strode the Emperor in evening dress, white kid gloves, heavily starched linen, neat pearl studs, and jet-black face.

"Got up just as though he were going to sing Spirituals at a party," said Lady Courteney.

The racism that poisons Waugh's pen will make Black Mischief a difficult, if not impossible, read for tender souls, but I think that it's possible to get beyond it and enjoy the book's deeper satire, which has not race but planned economy (eg Communism) as its target. Then again, I'm not black. If it's any comfort, Waugh thought little better of Americans.

Basil tries to catch the Emperor's eye, but in vain. "I don't believe he remembers me." In fact, it is just the opposite.

But the Emperor sat tight. Seth recognized [Basil] in his first grave survey of the restaurant and suddenly, on this triumphal night in his own capital, he was overcome by shyness. It was nearly three years since they last met, and Seth recalled the light drizzle of rain in the Oxford quadrangle, a scout carrying a tray of dirty plates, a group of undergraduates in tweeds lounging about among bicycles in the porch. He had been an undergraduate of no account in his College, amiably classes among Bengali babus, Siamese and grammar school scholars as one of the remote and praiseworthy people who had come a long way to the University. Basil had enjoyed a reputation of peculiar brilliance among his contemporaries. On the rare occasions when evangelically-minded undergraduates asked Seth to tea or coffee, his name occurred in the conversation with awed disapproval. He played poker for high stakes. His luncheon parties lasted until dusk, his dinner parties dispersed in riot. Lovely young women visited him from London in high-powered cars. He went away for week-ends without leave and climbed into College over the tiles at night. He had travelled all over Europe, spoke six languages, called dons by their Christian names and discussed their books with them.

Basil's glamour - or the recollection of it - paralyses the Emperor. The festivities continue, and almost boil over upon the arrival of a tribal dignitary.

It was one of the backwoods peers, the Earl of Ngumo, feudal overlord of some five hundred square miles of impenetrable highland territory. He had occupied himself throughout the civil war in an attempt to mobilise his tribesmen. The battle of Ukaka occurring before the levy was complete, saved him the embarrassment of declaring himself for either contestant. He had therefore left his men in the hills and marched down with a few hundred personal respects to the victorious side. His celebrations had lasted for some days already and had left some mark upon even his rugged constitution.

Told that there are no free tables, the Earl persists in asking for one. The scene is saved by the sight of Seth, which prompts a gesture of homage from the Earl. The Emperor is gracious, but even as he vacates his box (thus saving Prince Fyodor serious vexations), he rues his subjects' rustic behavior, and dreams, "If I had one man by me whom I could trust ... a man of progress and culture ..." Anybody who doesn't know what's going to happen next is very new to fiction.

There follows the briefest of interludes, "Six Weeks Passed." It's a cinematic tour of a peaceful Azania, from the dusty streets of Matodi to "the low Wanda coast where no liners called, and the jungle stretched unbroken to the sea." Six weeks is just enough time for Chapter Five to open at the Ministry of High Commissioner, where Basil, the Minister, assisted by the unavoidable Krikor Youkoumian.

If nothing else - and it is a great deal else - Chapter Five provides a lesson in the limits of government. Under good governments, these limits go unnoticed, because statesmen know where they lie and go nowhere near them. Modernisation, however, posits that the well-known limits are crippling, and it tends to throw out the idea of limits altogether in a wild burst of heavy-handed optimism. It no longer matters that the setting is a remote African island. Radical modernisation has foundered upon the same rocks wherever it has been attempted, and Waugh studs the action with so many small but telling missteps that, by the end of the chapter, the sagacious reader will see nothing but catastrophe just over the horizon. On the basis of Waugh's first two novels, one ought to bear in mind that this novelist doesn't mind killing off leading characters, or condemning others to unresolved, unpromising outcomes. The sagacious reader begins to fear for Basil in earnest.

A running joke throughout the chapter is the matter of boots for the army. A truly modern army, it will be conceded, marches booted into battle. On top of that, Mr Youkoumian is interested in a shipment of shoddy boots from South Africa; he intends to resell it to the government at a good price. (Mr Youkoumian would be incapable of drawing a line, or even imagining one, between "public" and "private sector.") The difficulty is that the Azanian army, according to General Connolly, would be lamed by footwear of any kind. Basil's initially cordial relationship with the General quickly deteriorates. For Basil has pretty much become the dictator of Azania. All the other ministers have acquired rubber stamps in order to Refer to Ministry of Modernisation. Everything is more or less up to him. Or would be, if the Emperor, once so modest and progressive, weren't becoming, in victory, quite so imperial. Seth spends his days reading strange books that fill him with strange ambitions. Astronomers - he requires the best available. "Ectogenesis" (fetal gestation in bottles) - get someone on it. He summons Basil at all hours to propose hare-brained schemes for the improvement of his realm, and eventually, under all the stress, Basil begins to snap, muttering very traitorous asides to Mr Youkoumian. When, at the end of the chapter, he learns that Seth has quietly had a lot of Azanian banknotes printed in Europe, and is trying to circulate them, Basil asks, "What's that black lunatic been up to this time?"

But the banknotes, though very bad, are not the worst. The worst is a contraception campaign that will, if implemented, truly bring Azania up-to-date. Waugh had converted to Roman Catholicism in 1930, and with the ill-advised contraception campaign, the conservative novelist arms himself with an issue round which those who honor tradition - especially the peasants who don't believe that they have a choice - can gather with enthusiasm. Seth and Basil have such a mean understanding of tradition that they don't reckon with its force, or try to exploit it to their own ends. In a wicked detail, Seth studies Soviet Constructivist posters, and then works with an artist to realize his scheme. The poster bears two images. To one side, "a native hut of hideous squalor" awash with underfed children; to the other, "a bright parlour furnished with chairs and a table" - and one child. In between, a condom. The condom, clearly, is to be associated with the more favorable image. Trouble is, the vast bulk of Azanians prefer the hut to the parlour.

See: on right hand: there is rich man: smoke pipe like big chief: but his wife she no good: sit eating meat: and rich man no good: he only one son.

See: on left hand: poor man: not much to eat: but his wife she very good, work hard in field: man he good too: eleven children: one very mad, very holy. And in the middle: the Emperor's juju. Make you like that good man with eleven children.

So the people come to associate condoms with fecundity.

To make things worse, Seth has taken up city planning, and soon convinces himself that the great stone Anglican cathedral is in the way of one of his Parisian boulevards. Sir Samson is not displeased to learn that one of these will be named after him.

You never know. Debra-Dowa may become a big city one day. I like to think of all the black johnnies in a hundred years' time driving up and down in their motor cars and going to the shops and saying "Number a hundred Samson Courteney" and wondering who I was. Like, like ..."

"Like the Avenue Victor Hugo, Envoy."

"Exactly, of like St James's Square."

That has to be the deepest joke in the book. I'm not sure I can take it all the way down, but I can feel it.

Prudence, predictably, attaches herself to the exciting Basil Seal, but they don't have much time for dalliance, thanks to the Emperor's importunities. She continues to work on her Panorama of Life as fatuously as ever. William is obliged to ride around with her pony in tow, but he doesn't do it in very good grace.

Meanwhile, M Ballon of the French Legation makes an ally of General Connolly - now the Duke of Ukaku - to bring his wife to a dinner. This is a first for the Black Bitch, and she is beside herself with delight. The scene in which she receives the invitation - not that she knows what it is yet - is perhaps the most difficult for anyone of liberal sentiments to read.

The Duchess was left alone with her large envelope; she squatted on her heels and examined it, turning it this way and that, holding it up to her ear and shaking it, her head sagely cocked on one side. Then she rose, padded into the house and across the hall to her bedroom; there, after circumspection, she raised a loose corner of the fibre matting and slipped the letter beneath it.

Two or three times during the next hour she left her wash-tub to see if her treasure was safe. At noon the General returned to luncheon and she handed it over to him, to await his verdict.

One blushes to think how much laughter this passage must have excited in the more sophisticated county drawing rooms.

What has up to now been a satirical but relatively static portrait, not much troubled even by a civil war, now becomes a fateful cascade of dominoes. The boots, you ask? What about the boots? General Connolly is only too happy to announce that, upon their distribution, his men threw a great feast and - ate them.

Chapter Six

The contraception pageant, catastrophically interrupted by traditionalist Azanians, is the major action of this chapter - just as any intelligent reader would foresee. Quite unexpected is the point of view from which it is witnessed. Waugh introduces two new characters, Dame Mildred Porch and Miss Sarah Tin, earnest leaders of the Dumb Chums Club, an animal-rights organization. The ladies have interrupted their return from South Africa to investigate Azanian horrors. They are indomitable types who get on by ignoring inconvenient facts and threatening to "tell the Foreign Office." They clearly prefer animals to human beings but have no idea why everyone wouldn't share this preference. Waugh has a lot of fun toasting them. The unsoundness of Dame Mildred is brought through when she writes to her husband,

I enclose cheque for another month's household expenses. The coal bill seemed surprisingly heavy in your last accounts. I hope that you are not letting the servants become extravagant in my absence. There is no need for the dining-room fire to be lit before luncheon at this time of year.

The letter is followed by diary entries that eloquently betray Dame Mildred's unbearable personality.

No news train. Wired legation again. Unhelpful answer. Fed doggies in market place. Children tried to take food from doggies. Greedy little wretches. Sarah still headache.

Presently the ladies arrive at Debra-Dowa, where they are shocked not to be put up at the Legation. Installed at Youkoumian's Hotel, they meet Basil Seal (Dame Mildred knows his mother), and note that he is tired and that he goes to bed early - slyly introduced evidence that serving as Minister of Modernisation has worked a change on Basil. On March 14th, Dame Mildred notes that she and Sarah have encountered a "quaint caravan - drums, spears, etc." on one of their walks.

Other people besides Dame Mildred were interested in the little cavalcade which had slipped unobtrusively out of the city at dawn that day. Unobtrusively, in this connection, is a relative term. A dozen running slaves had preceded the procession, followed by a train of pack mules; then ten couples of mounted spearmen, a platoon of uniformed Imperial Guardsmen and a mountain bad, blowing down reed flutes eight feet long and beating hand drums of hide and wood. In the centre on a mule loaded with silver and velvet trappings, had ridden a stout figure, heavily muffled in silk shawls It was the Earl of Ngumo travelling incognito on a mission of great delicacy.

Waugh takes his time - much to our pleasure - unwinding the plot against Seth. According to the Nestorian Bishop (a virulent opponent of the contraception campaign), Seth's mother, the late Empress, had a brother who was taken away in chains as a boy and imprisoned in a cave, where he has remained ever since. The Earl of Ngumo is deputed to retrieve him from incarceration and mount him on the Azanian throne.

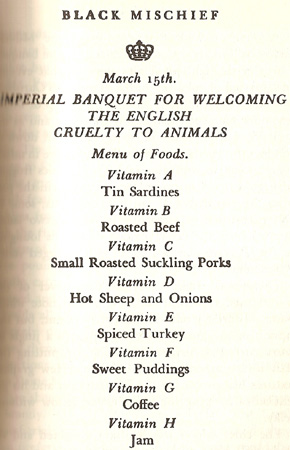

Meanwhile, Seth gives a banquet for the visiting Englishwomen. The menu is very advanced in its way.

As the menu suggests, the ladies' mission has not been properly comprehended by the Azanians; this becomes even clearer when the sinister Viscount Boaz proposes a toast.

Ladies and gentlemen, we must be Modern, we must be refined in our Cruelty to Animals. That is the message brought to us by our guests this evening.

The rescue and retrieval of Achon, Seth's uncle, occupies a few pages of crackling satire.

After this all important admission they sat for some time in silence; then the Abbot rose and with ample formalities left his guest to sleep. Both parties felt that the discussion had progressed almost too quickly. There were decencies to be observed.

Decencies that stand in sharp contrast to the emaciated prisoner.

The prince was completely naked, bowed and shrivelled, stained white hair hung down his shoulders, a stained white beard over his chest; he was blind, toothless and able to walk only with the utmost uncertainty.

Back in Debra-Dowa, Dame Mildred is having no success in getting the attention of the Legation. William Bland actually hangs up on her. She decides that they are wasting their time in Azania, but she has no idea that the ladies of the diplomatic quarter - all except the English - are quietly packing for what will be the last train to Matodi. Walsh, at the Legation, tries to warn Sir Sampson, but it's in vain.

"Pooh, another of these native disturbances. I remember that last civil war was just the same. Ballon thought he was going to be attacked the whole time. I'd sooner risk being bombed up here than bitten by mosquitoes at the coast. Still, jolly good of you to tell me."

Basil has no more luck with Seth.

"Seth, there's a lot of talk going about. They say there may be trouble tomorrow."

"God, have I not had trouble today and yesterday? Why should I worry about tomorrow?"

On the day of the pageant, Dame Mildred is happy to note that the Emperor will have good weather. Things to downhill from there, or, if you prefer, up onto a hot tin roof. Their rooms occupied by people who want to watch the parade in comfort - the staff has melted away - Dame Mildred and Sarah are forced to take refuge on the parapet of the hotel. They see the beginning of the pageant - schoolgirls from "the Amurath Memorial High School, an institution founded by the old Empress to care for the orphans of murdered officials" carry a banner announcing that "WOMEN OF TOMORROW DEMAND AN EMPTY CRADLE" - but they lie low when the mayhem breaks out, for fear of being shot. When things quiet down, they're so hungry and thirsty that they resort to drinking Youkoumian's swill. The bottle comes in handy when a car from the Legation drives up and almost leaves without them. Lady Courtenay, worried about their safety, has insisted that William and another staffer drive to the hotel to check up on them; Sir Samson has ordered them, however, on no account to return with the ladies. Needless to say, William is no match for Dame Mildred.

Dame Mildred, putting little trust in Miss Tin's ability to restrain the diplomats without her, took few pains with the packing. In less than a minute she was down again with an armful of night clothes and washing materials. At last with a squeeze and a grunt she sank into the back seat.

"Tell me," asked William with some admiration, as he turned the car round. "Do you always throw bottles at people when you want a lift.

Presenting the unraveling of Seth's regime through the eyes of Mildred Porch enables Waugh to underscore the futility of high-minded but clueless meddling with a fresh color. Knowing nothing of the late civil war - "How little the papers tell us" - Dame Mildred and Miss Tin descend upon Debra-Dowa with a belief in their cause that, under the circumstances, appears nothing less than demented. In standard Anglo-American fashion, their expectation that people will be reasonable is a thin cover for their cracked belief that nobody with a brain would behave other than as they do.

"Hot Sheep and Onions" - yum! Presented with the menu ahead of time by Seth, Basil finds that he is too tired to suggest the "emendations" that occur to him. "That's fine, Seth; go ahead with that."

Chapters Seven and Eight

With a great deal up in the air, Waugh begins the last substantial chapter on a sustained note of calm. First there is Sir Samson's displeasure at the overrunning of the Legation by "the entire English population of Debra-Dowa." He overhears his uninvited guests describing the preceding days' riots and retires to the Chancery, where all the young aides are playing "cut-throat bridge." Presently the Envoy asks William to don a uniform and take his place at the coronation of Achon, which has just been announced. The scene shifts to the Nestorian cathedral, and the spectacle is described with the faintest mockery - mockery so faint, in fact, that it constitutes a kindness. It is clear that Waugh is of a divided mind when it comes to this elaborate but rather pagan ceremony. He can't help sneering, but he reminds himself to be reverent. The result is the book's first pathetic moment, as the formerly incarcerated Emperor is led to the throne.

It was not clear from his manner that he understood the nature of the proceedings. He wriggled his shoulders irritably under the unaccustomed burden of silk and jewelry, scratched his ribs and kept feeling disconsolately towards his right foot and shaking it sideways as he walked, worried at missing his familiar chain. Some drops of the holy oil with which he had been recently annointed trickled over the bridge of his nose and, drop by drop. down his white beard. Now and then he faltered and halted in his pace and was only moved on by a respectful dig in the ribs from one of his attendant peers.

The Emperor manages to complete the first two parts of his oath (with grunts), but the moment of coronation is too much for him.

With great gentleness, [the Patriarch] placed it over the wrinkled brow and straggle of white hairs; but Achon's head lolled forward under its weight and the bauble was pitched back into the Patriarch's hands.

...

For Achon was dead.

With Achon's death, the coup is a bust, and chaos doesn't take long to resume its swirling. Feckless William reports back to the Legation knowing little more than that contact with Matodi (and escape) will be impossible for some time. It is Basil who shows up with the inside dope. He has disguised himself as a Sakuyu merchant. He warns his countrymen that they will not long be safe at the Legation. After regaling the company with half-invented tales of Sakuyu savagery, Basil advises the Envoy to devise a plan for the Defense of the Legation.

And the Envoy Extraordinary could find nothing to say. The day had been too much for him. Every one was stark crazy and damn bad-mannered too. They could do what they liked. He was going to smoke a cigar, alone, in his study.

Basil took command.

He takes command and is effective, yes, but he remains Basil the mischievous.

An attempt to deceive the children that nothing unusual was afoot proved unsuccessful; it was not long before they were found in a corner of the hall enacting with tremendous gusto the death agonies of the Italian lady whose scalp was eaten by termites.

"The gentleman in the funny clothes told us," they explained. "Coo, mummy it must have hurt."

After an uneventful night, the company assembles on the lawn. Rain clouds are perceived, and the gong of sublime cluelessness is sounded for the last time.

"That's rain, all right," said Basil. "I was counting on it today or tomorrow. They got it last week in Kenya. It'll delay the repairs on the Lumo bridge pretty considerably."

"Then I must get those bulbs in this morning," said Lady Courteney. "It'll be a relief to have something sensible to do after tearing up sheets for bandages and sewing sandbags. You might have told me before, Mr Seal."

Lady Courteney is advised to inventory her stores, but in the event that proves unnecessary. A plane flies over the compound and drops a message. The message instructs the Envoy to have everyone ready for evacuation within the hour. Walsh is flying to the rescue from Matodi.

During the frenzy of packing, Basil, "suddenly reduced to unimportance," embraces Prudence for the last time before parting; he is resolved to stay on hand to help sort things out. Which is just as well, since Prudence is repelled by the odd smell of his garments.

Quite soon, before any one was ready for them, the five aeroplanes came into sight, roaring over the hills in strictly maintained formation. They landed and came to rest in the compound. Air Force officers trotted forward and saluted, treating Sir Samson with a respect which somewhat surprised his household.

Note the respect with which Waugh treats the real military men. They're capable and efficient, and there are things that Waugh won't make fun of. Prudence holds up everything by running back to the house to retrieve her silly book, Panorama of Life. Then she boards one of the bomber planes.

And, wouldn't you know, it's the plane that develops engine trouble. The pilot manages to land in a clearing, and he assures Prudence that he'll have the plane fixed in no time, but we are not so sure, are we, as Waugh turns to Basil, who is trekking toward his rendezvous with Boaz and Seth. Along the way, he intercepts a perfidious missive from Boaz to Ngumo. Gradually his servants melt away in the rain.

Waugh begins to wrap things up, with occasional echoes from the first chapter.

Confusion dominated the soggy lanes of Matodi. ...

Amidst mud and liquid ash at Debra-Dowa....

Among the dry clinkers of Aden, Sir Samson and Lady Courteney waited for news of the missing aeroplane...

And, finally, Basil reaches his employer's camp. The remainder of the chapter is quite somber, and anticipates the Waugh's wartime fiction. In the absence of women and effete men, humor is hard to come by, but Waugh finds scraps in the face-saving games that Boaz's men try to play with Basil. Given the fact that Boaz is dead drunk and that Seth is apparently dead, the humor is decidedly that of the gallows. This is in any case Basil's great moment. We must recall that, while a scamp, Basil has never been a fool, and now he rises to the call of honor, directing the men to prepare to convoy Seth's body to Moshu, the city of his people, where his body will be burned according to custom. Now that we are in unadulteratedly native territory, Waugh the travel-writer steps to the fore. The city is described with neutral interest, as is the immolation scene. Only the fulsome funeral oration is mockable - but we don't mock it; we mourn Seth. We recall that Seth, while a great fool, only wanted the best for his people; his downfall was the product of the quality that all good conservatives lack: impatience.

The funeral feast begins and Basil "drew back a little" and finds himself beside the headman of Moshu, who is very drunk. He offers his drink to Basil, who declines twice. Then he pulls "from his bosom" a hat, which he puts on his head. Basil recognizes it at once as Prudence's hat.

"But the white woman. Where is she?"

But the headman was lapsing into coma. He said "Pretty" again and turned up sightless eyes.

Basil shook him violently. "Speak, you old fool. Where is the white woman?"

The headman grunted and stirred; then a flicker of consciousness revived in him. He raised his head. "The white woman? Why, here," he patted his distended paunch. "You and I and the big chiefs - we have just eaten her."

Then he fell forward into a sound sleep.

We're not told what Basil's reaction is. "Round and round circled the dancers," and on that note, the chapter ends.

The short final chapter is a send-off in two scenes. The first finds Basil back in London, visiting Sonia and Alistair in their flat. Sonia quizzes Basil a bit but forbids him to tell her anything about his time in Azania.

"Can't think what you see in revolutions. They said there was going to be one here, only nothing came of it. I suppose you ran the whole country."

"As a matter of fact, I did."

"And fell madly in love."

"Yes."

"And intrigued and had a court official's throat cut." [That would be Boaz.]

"Yes."

"And went to a cannibal banquet. Darling, I just don't want to hear about it, d'you mind? I'm sure it's all very fine and grand but it doesn't make much sense to a stay-at-home like me." We last see Basil off on his way to his lover and patroness, Angela Lyne. She, one expects, will hear him out.

The final setting is Azania, now a joint French and British mandate by the League of Nations. We overhear two "Arab gentlemen" taking the air along the seawall, discussing all the changes, which include a paved highway to Debra-Dowa and a colony of bungalows (the domestic hallmark of the British Raj in India) just above Matodi. The focus is relayed to the English passengers of a passing car, whom we follow up to the bungalows. The ensuing scene involves a courtly dance of bureaucratic deference played by people named Bretherton, Reppington, and Lepperidge whom one is not meant to keep track of. At dinner, a Mr Grainger discusses the thorny case of General Connolly and his "wog" duchess. Now that the British are running the show, adventurous spirits like Connolly are completely de trop, and if the loving couple has to be separated - because there "aren't many places would have them" - that's tough.

The novel ends to the strains of a gramophone playing Gilbert & Sullivan in the Portuguese Fort.

It is customary to speak of Waugh's wit as "savage," and in Black Mischief he may be said to savage the savages even as he skewers the Europeans. But his savagery, while equally exuberant and unchecked, has an element that the "native's" lacks: knowingness. It is a knowingness that enables him to break completely with the tradition, in English fiction, of distinguishing between shocking sensationalism (for the masses) and polite social comment (for the classes). Written with an understatement that is intelligible only to sophisticated readers will, the novel has at the same time no manners, or, worse, positively bad manners. As a novelist, Waugh behaves very much like Basil Seal. He has absolutely no respect for what the French call les bienséances, and is always on the lookout for new ways in which to flout them. That's what makes the savagery of Black Mischief so exciting to read. True, today's reader is much harder to shock than his counterpart in the early Thirties. But Waugh has cleverly (if unconsciously) inserted a heuristic: Sir Samson and Lady Courteney, to name only two, are examples of the kind of reader whom Waugh meant to outrage. Their responses to events parallel a genteel reader's response to the story. The novel teaches us, gently but firmly, what's supposed to be funny.

Then again, I speak as someone who was in his teens when Waugh died. You shall have to see how well Waugh's achievement makes itself intelligible in future. (December 2005 - June 2006).

Copyright (c) 2006 Pourover Press