Click above to visit the entire site

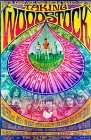

Taking Woodstock

Ang Lee

At

the end of Taking Woodstock, Michael Lang (Jonathan Groff) leans down

from a white horse in answer to an old friend's question (what's next?): a

Rolling Stones concert in San Francisco, bigger and more beautiful than the one

that has just ended. The old friend, Elliot Teichberg (Demetri Martin) smiles

with admiration, but we know that the next concert — the dark twin of Woodstock,

Altamont — will not be beautiful. The irony of Lang's expectation is one of many

ways in which Ang Lee's film signals that the event constituted the end of

something, not, as so many felt at the time, a beginning.

At

the end of Taking Woodstock, Michael Lang (Jonathan Groff) leans down

from a white horse in answer to an old friend's question (what's next?): a

Rolling Stones concert in San Francisco, bigger and more beautiful than the one

that has just ended. The old friend, Elliot Teichberg (Demetri Martin) smiles

with admiration, but we know that the next concert — the dark twin of Woodstock,

Altamont — will not be beautiful. The irony of Lang's expectation is one of many

ways in which Ang Lee's film signals that the event constituted the end of

something, not, as so many felt at the time, a beginning.

Mr Lee honors the miracle of Woodstock — the by-and-large cheerful endurance of roughly half a million young people of staggering inconveniences that never quite amounted to privation — in the quietest way possible, by not denying it. He is not really interested in the peace and love angle. It's chaos that catches his fancy, and there has almost certainly never been as smoothly-graded a feature-film-length presentation of mounting disorder. The disorder is apparently harmless — nobody gets hurt in any palpable way — but, by the end of Taking Woodstock, we have been shown that crowds, however well-intentioned, can be as destructive without resorting to violence. It's the kind of destruction that is easily confused with liberation.

Taking Woodstock begins by pretending to tell a backstage story about how a young man, desperate to save his parents from bankruptcy and in possession of a plausible permit, hooked up a childhood friend with a neighboring farmer to stage what will always be the most famous rock concert of all time. The farmer was Max Yasgur, and, as everyone knows, Woodstock was held on his property. The adjoining El Monaco motel, however, would serve as operations headquarters, and Elliot Teichberg would bring in more than enough money to pay off his parents' mortgage. Happy ending? Not really, as we shall see. But the beginning is certainly funny. The elder Teichbergs, Jake (Henry Goodman) and Sonia (Imelda Staunton), are a very familiar sort of odd couple. Jake is hapless, feckless, and just generally -less. It's surprising that he's alive — a point that he himself makes at the end. Sonia is a grand-guignol combo of guilt-shattering Jewish mother and paranoid Holocaust survivor; she is no longer capable of taking in new information, but refracts everything that she hears through what she already knows. Her radical frugality has made the motel uninhabitable, although perhaps it has also staved off foreclosure. Foreclosure, in any case, now looms, at the beginning. Poor Demetri, in thrall to parental neediness, quits his Manhattan apartment and his interior decorating business (he also stops painting) in order to give the El Monaco one summer's final chance.

Dutiful and even resourceful, Elliot is an optimist by necessity, and when he learns that a neighboring town has killed plans for a "rock festival," he seizes the opportunity and makes a phone call. Helicopters land, and squadrons of somber, suited men explore the Teichberg's property. It is found to be largely a swamp, but, Elliot, ever resourceful, thinks of his neighbor, Max (Eugene Levy). Soon the suits are replaced by construction workers. The natives — the gentile natives, at any rate — are not happy, and Sonia fears pogroms or worse. Instead of hooligans, however, yet more construction workers appear. Polite young people show up to buy tickets. Mr Lee begins to use the same split-screen technique that is a hallmark of Woodstock, Michael Wadleigh's amplified documentary of the concert. Elliot rushes from place to place, putting out fires, and there are always and everywhere more people in the frame. When some protection-racketeers show up, and are shown the door by a bat-wielding Jake (who is coming to life), we notice the single line of gently moving vehicles in the road in front of the motel. Presently the road is a clotted parking lot that even a motorcycle cop cannot speed through. The next thing you know, Elliot scoots over to the Yasgur farm, makes some new friends, drops some acid, and watches the whole scene pulsate like a massive science fiction blob. Fade to white.

The rest is downhill. It's gentle, and it's not not funny. But when Elliot gets back to his own place — it seems astonishing that he has retained possession, in the mounting bedlam, of a private bedroom — he learns from his fairy godmother, Vilma (a cross-dressing Marine played by Liev Schreiber in a stunning, if louche, female impersonation of Kim Cattrall), that his parents have ingested some strong hash brownies. The normally stony Sonia is whooping and hollering in the backyard, doing some quaint Central European dos-à-dos with Jake. You worry that the couple will die laughing, but they snore gently when they fall asleep, and Elliot thoughtfully covers them with blankets. In the morning, the scene is not so funny. Sonia is discovered not in bed but sprawled in a pile of money. It turns out that she has squirreled away $97,000 over the years — and still accepted Elliot's enormous financial sacrifices. Elliot doesn't cry or stage a tantrum, but never has a cinematic childhood come to a sharper end.

There are two pivotal scenes. Whether you respond to the second one, in which Elliot and his damaged Vietnam-veteran buddy, Billy (Emile Hirsch), slide gleefully down a muddy runway into a puddle of muck, as liberating or nihilistic will probably indicate broader feelings about the legacy of the Sixties. In the earlier one, clusters of naked hippies frolic and cavort in the pond portion of the Teichbergs' swamp. (Mr Lee is probably to be commended on his use of period physiques.) Elliot, his father, and Vilma stand by on the bank, laughing. What sounds like distant thunder resolves into distant rock music: Woodstock has begun. It is a beautiful moment, but its seamlessness conceals the end of the Catskills-comedy portion of Taking Woodstock, and the beginning of the liberation-through-creative-destruction part. Matching up the pattern of one young man's life with the epic phenomenon of Woodstock ought to be absurd, but Ang Lee makes it a perfect fit. (August 2009)

Copyright (c) 2009 Pourover Press