Click above to visit the entire site

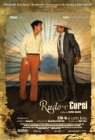

Rudo y Cursi

Superficially, Carlos Cuarón's Rudo y Cursi — the film takes its

title from the real name of one of its anti-heroic half brothers and the nom

de bol of the other — is a dry and bittersweet comedy presented in exuberant Latino colors.

Beneath the surface, however, lie the compelling satisfactions of the best-known Biblical fables, and

these gives the film the

air of an grand religious festival, of a morality play performed on the steps of a cathedral. What

is really just the story of two jerks from the sticks takes on the shimmer of world-historical

importance, just as the story of Cain and Abel, thanks to its position in a well-known book, is

somehow more powerful than a tale of resentful fratricide ought to be. We might

also think

of the fall of Adam and Eve, not because Mr Cuarón's story echoes it but because, despite

its reasonably large cast, Rudo y cursi is a show for two mortals and a devil.

Superficially, Carlos Cuarón's Rudo y Cursi — the film takes its

title from the real name of one of its anti-heroic half brothers and the nom

de bol of the other — is a dry and bittersweet comedy presented in exuberant Latino colors.

Beneath the surface, however, lie the compelling satisfactions of the best-known Biblical fables, and

these gives the film the

air of an grand religious festival, of a morality play performed on the steps of a cathedral. What

is really just the story of two jerks from the sticks takes on the shimmer of world-historical

importance, just as the story of Cain and Abel, thanks to its position in a well-known book, is

somehow more powerful than a tale of resentful fratricide ought to be. We might

also think

of the fall of Adam and Eve, not because Mr Cuarón's story echoes it but because, despite

its reasonably large cast, Rudo y cursi is a show for two mortals and a devil.

Since I don't know much about soccer, I can't tell you what position Tato (Gael García Bernal) plays, but Rudo (Diego Luna) is a goalie. This is as neat a way as any of saying that, to the extent that the brothers will interact, they will do so as opponents. Although the brothers openly acknowledge the strength of the family ties that bind them, cooperation does not come naturally. What comes naturally is competition. They compete for their mother's love; they compete for their teams' shirts. So we're told anyway, by the voice of the devil, who lays down a lot of baroque Latino force-of-destiny proverbializing that would be hard to take seriously if the pace of the film were not so tight.

We have two dimwits dwelling, if not in Paradise exactly, then in a contented subsistence that, if life were kind, would be enough for them. But they have dreams (akin to Eve's thirst for forbidden knowledge), and when they are seduced by a wise old serpent, they drop effortlessly into his hand — first one, then the other.

On their way to a soccer match one weekend morning, Rudo and Tato encounter a gentleman (Guillermo Francella) in a spiffy red sports car with a flat tire. The brothers are happy to help out, and one thing leads to another. The next day, or so it seems, Tato is in the back seat of the spiffy sports car, headed for Mexico City. The only question is, how long will it take Rudo to follow. But Batuta (as the older gentleman is called) is a methodical worker. First, he plants Tato where he wants him, and makes sure that he's growing in just the right way. Only then does he make the call to Rudo.

I couldn't figure out just how or why Tato gets saddled with the nickname "Cursi." It's not a compliment: beber con el dedo meñique en alto es de lo más cursi means "sticking out your pinkie when you sip tea is the height of bogus refinement." Tato doesn't like the name, but he's easily distracted by the perks of life as a hot soccer player. That is the whole point of Batuta's exercise. In no time at all, Tato has made a music video, occupied a big house, and won the affections of the beautiful Maya.

Rudo is the darker brother; he would be Cain. Rudo is one of those anxious swaggerers who scare themselves into disasters; if they would just calm down and not worry about insults to a manhood in which they themselves scarcely believe, life would go much more smoothly. Rudo is also a virtuoso of improvidence: there isn't anything he won't gamble away — and he doesn't have to own it, either, as Tato finds out when he comes home to an empty mansion. Batuto sedulously introduces Rudo to a "Las Vegas" type gambling-hall operator, and in no time at all Rudo is in trouble with the loan sharks.

Having placed the brothers on opposing teams, now all Batuta has to do is undermine Tato's confidence and tighten the screws on Rudo's debt. As Batuta's con sprouts its full foliage, we're impressed by the elegance of the arrangement. Mr Francella's devil is about as appealing as a devil can be. His wide-open, clear eyes seem flushed with benevolence, but his smile is lupine and his glibness might as well be a pointy tail. It's nice to see, in the final sequence, that Batuta is a very mortal devil, vulnerable to setbacks — especially as he shows no signs of reforming, but is modestly determined to get back to where he wants to be.

The comic pratfall of knowing one's right from one's left is exactly the kind of simple and basic device that Mr Cuarón and his two young stars know how to polish off and present to the audience as if we'd never seen it before. How fitting that this, of all things, should be the devil's undoing. (June 2009)

Copyright (c) 2009 Pourover Press