Click above to visit the entire site

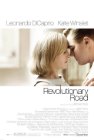

Revolutionary Road

Sam Mendes's Revolutionary Road is one of the most terrifying films that I

have ever seen. There are no physical shocks, no surreal horrors — just the inescapable

intimacy of twe people in a great deal of pain. The strategy adopted by Mr Mendes and his two

stars — his wife, Kate Winslet, and her Titanic costar, Leonardo di Caprio — is

to rebuff any attempts at audience identification with Frank and April Wheeler, an unhappy

suburban couple. Frank and April are as likely to be repulsive as they are to be appealing, and

moreover it is hard to know which they're going to be next.

The extent to which suburban life is intended to be condemned remains unclear, but whether or

not it is the contributor to the Wheelers' malaise

that April and, to a lesser extent, Frank feel it to be, it is an appropriatre backdrop

to the asphyxiation of young dreams. The dreams might have died anywhere, but it is

clear that they could not survive in the Wheelers' "colonial" home.

Sam Mendes's Revolutionary Road is one of the most terrifying films that I

have ever seen. There are no physical shocks, no surreal horrors — just the inescapable

intimacy of twe people in a great deal of pain. The strategy adopted by Mr Mendes and his two

stars — his wife, Kate Winslet, and her Titanic costar, Leonardo di Caprio — is

to rebuff any attempts at audience identification with Frank and April Wheeler, an unhappy

suburban couple. Frank and April are as likely to be repulsive as they are to be appealing, and

moreover it is hard to know which they're going to be next.

The extent to which suburban life is intended to be condemned remains unclear, but whether or

not it is the contributor to the Wheelers' malaise

that April and, to a lesser extent, Frank feel it to be, it is an appropriatre backdrop

to the asphyxiation of young dreams. The dreams might have died anywhere, but it is

clear that they could not survive in the Wheelers' "colonial" home.

When April first sees the house that she and Frank will buy — as we're shown in one of the film's few, brief flashbacks — her face lights up richly, and it's clear that a dream has come true. What does April like about the house? We're not told. We never see her happy inside it. But then that is where she lives, inside the house, not outside it. Whatever she likes about her house disappears as soon as she crosses the threshold. But then no one is special at home.

Frank and April Wheeler are afflicted by the notion that they are special, and that their specialness, palpable but visible only to them, will be revealed to the world while at the same time bestowing a sense of significance that, for the time being, remains unrealized. Living in expectation of transcendence while putting up with the humdrum everyday circumstances of their lives — she the homemaking mother of two, he a copywriter in a large firm's marketing department — inevitably becomes exhausting, but the Wheelers work hard to sustain their faith in brilliant futures. The film begins (as does Richard Yates's 1961 novel) with a thunderbolt of evidence to the contrary, as the curtain rings down on a distinctly underwhelming performance of The Petrified Forest by an amateur production in which April has starred. Frank is winningly supportive at first, but when April, more startled than crushed, rejects his kindness, he turns mean. In world-historical terms, the Wheelers' problems are less than nothing, but as they snarl at each other on a highway shoulder they look like victims of a terrible catastrophe, something involving an earthquake at least. They have fought before, but the damage that they do to one another now, trailing as it does the publicity of April's failure as an actress, promises to be irremediable.

It's no surprise, then, that April wants to leave the house on Revolutionary Road. But her rally is truly ambitious: she calculates that she, Frank, and the children can subsist for six months on their savings, and that the place to do the subsisting is Paris (France), where, April is sure, she'll eventually get a secretarial job in one of the big US agencies there, such as NATO. Meanwhile, Frank will find out what he wants to do with himself. This wild plan might work if put immediately into practice, but the Wheelers dither; April, certainly, does not intend to escape suburbia without gloating about it. Having made the decision to relocate to Europe is not very different from making the decision to be "special."

One feels that, on her own, unencumbered by Frank or family, April might just make a success of living in France. Her withering vividness and her statuesque grandiosity might strike just the right exotic note on the Rive Gauche. But Frank is too passive for such experiments. He is used to having things come his way, even if he doesn't really want them. Thus a marketing campaign that he spins out in a fit of contempt for his job turns out to be a "crackerjack": he is offered a promotion and a raise. And then April finds out that she is pregnant. It is one thing for Frank to agree to be supported by his wife. It is another to countenance her having an abortion — the child is one of those things that come his way, and he means to have it. Or rather, of course, he means for April to have it.

In Yates's novel, April is a discontented woman for whom things have not worked out very well. Within a few years of Revolutionary Road's appearance, female discontent would be anatomized, analyzed, and shown to be the inevitable consequence of thoughtless male prerogative. The idea that some women are spontaneously unhappy — or "hysterical" — has been utterly exploded. Mr Mendes and his screenwriter, Justin Haythe, have wisely resisted "explaining" April in today's terminology; nor, however, to they present her as a witch. She is a smart girl with ambitions at autonomy that are not smiled upon in her world. This makes her difficult to live with, but not inhuman. If it is true that no one will be offering her a raise and a promotion in order to keep her at her job, neither she nor Frank can spell out the inequity. Revolutionary Road is free of grievance: it takes us immediately to the pain that does not as yet know how to resist.

Indeed, the director and the screenwriter are to be commended for sparing us any talk of the Fifties as a decade of suffocating conventions. We're shown it generously enough, but always in a way that presumes some personal familiarity with the era. Just as April's feminism goes unglossed, so does the timidity of adults whom Frank and April live. Dylan Baker, Kathy Bates, Kathryn Hahn and David Harbour all turn in performances too idiosyncratic to taken as generalizing allegories. They are only familiar at first, before we know them. The one character who (spectacularly) fails to get with the program is the mentally-disturbed son of Ms Bates's positively-accentuated real estate broker, and Michael Shannon's delivery of this young man's candid observations warns us that only someone similarly disturbed would heed his judgments.

Thomas Newman's mood-setting score must not go unmentioned, even if it is extremely reminiscent of his work on Road to Perdition. There may be no gangland gunfights in Revolutionary Road, but fatality is just as likely. The discovery of one's ordinariness, brilliantly presented by Ms Winslet and Mr di Caprio, is a horror-movie theme for adults, and Mr Newman helps Mr Mendes to pull out all the stops. (January 2009)

Copyright (c) 2009 Pourover Press