Click above to visit the entire site

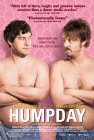

Humpday

Lynn Shelton

To do justice to Lynn Shelton's Humpday, I would

have to pore over a transcript of the dialogue. That's not because the characters say much that's intrinsically interesting.

But for the most part, they talk. Humpday is the action movie of talk.

Aside from a sprinkling of extras (the director among them), there are three

characters: Ben (Mark Duplass), his wife, Anna (Alycia Delmore), and his old

college friend, whom he hasn't seen in years, Andrew (Josh Leonard).

Instead of a romantic triangle, we have a conversational triangle, but it's not

what's said that's interesting. It's true that Anna has a lovely understated but

dramatic scene, in which she confesses to Ben that she "made out" with another man at a party while visiting a friend a while back (but definitely while she was married), but her words are not

polished. Anna's reasons for telling Ben about this lapse are very complicated, but the complications don't interfere with her straightforward narration. When Ben talks with Andrew, however, the language, no matter how superficially flat, is powerful defensive weaponry. When, by the cold light of

a hungover morning, the two men needle each other into following through on a

preposterous scheme that they improvised the night before, the pressure added by each contribution to the exchange is usually so slight as to be impalpable, but when the scene is over, you might be as exhausted as if you had just followed a particularly arduous round of bidding at bridge. Why, you might ask, are men who are supposed to be friends so wary of one another?

To do justice to Lynn Shelton's Humpday, I would

have to pore over a transcript of the dialogue. That's not because the characters say much that's intrinsically interesting.

But for the most part, they talk. Humpday is the action movie of talk.

Aside from a sprinkling of extras (the director among them), there are three

characters: Ben (Mark Duplass), his wife, Anna (Alycia Delmore), and his old

college friend, whom he hasn't seen in years, Andrew (Josh Leonard).

Instead of a romantic triangle, we have a conversational triangle, but it's not

what's said that's interesting. It's true that Anna has a lovely understated but

dramatic scene, in which she confesses to Ben that she "made out" with another man at a party while visiting a friend a while back (but definitely while she was married), but her words are not

polished. Anna's reasons for telling Ben about this lapse are very complicated, but the complications don't interfere with her straightforward narration. When Ben talks with Andrew, however, the language, no matter how superficially flat, is powerful defensive weaponry. When, by the cold light of

a hungover morning, the two men needle each other into following through on a

preposterous scheme that they improvised the night before, the pressure added by each contribution to the exchange is usually so slight as to be impalpable, but when the scene is over, you might be as exhausted as if you had just followed a particularly arduous round of bidding at bridge. Why, you might ask, are men who are supposed to be friends so wary of one another?

The nature of vernacular male friendship in contemporary America is Ms Shelton's subject, and she is an expert student. No one who has contemplated the weird and not particularly friendly way in which men who claim to be friends interact will be surprised by the discourse of Humpday, but the elegance of the presentation screws up beautifully against the mortification that Ben and Andrew suffer as they struggle against backing out on a dare. It's a dandy, at a louche soirée hosted by attractive lesbians, they get tipsy, stoned, and bold. They propose to make a pornographic film — starring only themselves. Humpday is as discomfiting as the most violent physical comedy, but the pratfalls are purely verbal. The men present carefully vetted and elaborately-qualified self-images with the fussiness of ancient lawyers writing escape clauses. They negotiate their bravado with a kind of grim recklessness, focusing on trying not to focus on what their negotiations are leading to.

The men are rarely altogether honest with one another, and no prevarication goes unpunished. At the end, if they've learned anything, it's how to regard the episode as a gigantic prank from which they both had the sense to pull back, before "things got out of hand." Or before either of them got out of his clothes. (Surely the funniest visual moment is the revelation that the two friends, stretched out on a motel bed with pillows coyly nestled in their laps, have been wearing their boxers all along.) Far from celebrating a reunion between old friends, Humpday shrieks with relief that no union has taken place. From behind the dread of unwanted sex, it announces that men can engage with one another only in terms of competition, not connection. The most humane thing that you can do with your old best friend is to pretend that you don't know him.

Together, Ms Shelton and her two actors make it as clear as a red traffic light that Ben and Andrew are revolted by the prospect of mutual physical intimacy. They are not afraid of being revealed as gay — that never crosses their minds. What does cross their minds, with an unpleasant insistence that skyrockets as the "shoot" draws closer, is the realization that, as Ben puts it, "There is nothing. That I would rather do. Less than this." Andrew says as much with his eyes, which Mr Leonard has clearly borrowed from some long-suffering hound dog. Or perhaps from a cow that is uncomfortable with abattoir lighting. In addition to his horror of touching his already middle-aged chum, Andrew has learned that Ben, by far the more articulate of the two, has complete control of the situation. Andrew seems to understand that if Ben decides to go ahead with the film project, he will be motivated by adult resolution, and not suppressed desire or curiosity. A deal is a deal, man. Andrew probably couldn't say which was worse, Ben's masterfulness or his masterliness.

Humpday has been marketed as a film about two friends, but Ben's character is far richer and more rounded than Andrew's. Precisely because we expect him to be the less interesting man he's the more interesting one. Since the days of his college hi-jinks with Andrew, Ben has pursued a career as some sort of transportation engineer; he has married Anna; he has bought a house; and now he would like to have a child. He has, in a word, grown up. When Andrew, who has not grown up, blows into his life in the middle of the night one summer, Ben is worried that he may be too grown up. Andrew embodies the youthfulness (you could call it immaturity) that Ben has left behind. Now, Ben wants to be grown up. But he does not want to be old.

So he makes a complete ass out of himself. He puts Anna through the ringer even before she learns about the movie proposal. Anna is clearly used to a totally adult Ben, and when her husband does not come home for dinner, and does not come home, in fact, until three in the morning, Anna really doesn't know what to think; it's obvious that life has taught her neither what to expect nor how to respond. I may have suggested that Mr Duplass is the star of Humpday, but Ms Delmore makes it a picture that must be watched. Anna is one of the most complete characters ever to address a camera. Sure of herself and unsure, by turns; now mousy, now gorgeous; a sweetheart and an avenging angel — Ms Delmore turns in a performance that shines through its very lack of diva turns. Ms Shelton sees to it that we measure the full weight of Anna's confusion as Andrew walks into her house and starts sucking up all the oxygen.

So when Ben assures Andrew that Anna is going to be "cool" with the project, we know this for the prevarication that it is; and when Anna finally finds out about it — from Andrew, of course — we can hear the thunder falling before the lightning darts from Anna's eyes. Ben's position is interestingly layered. On the one hand, he shows himself to be ahead of his bohemian friend. Although Andrew might have been expected to be relaxed about the porn project, he is anything but, because he is all hat and no cattle. (The saddest moment is Andrew's confession that he has never completed a single project.) On the other hand, Ben is in over his head with his wife, because he cannot square the vows that underlie their daily life with his determination to prove that he is not, appearances to the contrary notwithstanding, middle-aged. It is Ben who turns out to be an opportunist — albeit a desperate (and fundamentally decent) one.

Ms Shelton has pushed the brass tacks portion of the story into one final scene, but even here the friends' deceptively desultory bargaining is at the forefront. The extent of the Humpday's wild abandon is a kiss that climaxes what can only be called a running jump. There is also a hug, made awkward by the men's resolution to keep their groins as far apart as physically possible. While both actors are personably attractive in street clothes — Andrew sports a particularly jaunty fedora, a gift, he claims, from a princess in Morocco — neither man is in porn-star shape; and even if both men were buff, you feel, they would require a lot of direction. Everything about the strange but hilariously deflated climax, shot in a beige motel room, is anhedonic, visual saltpeter guaranteed to preclude the arousal of all but the most deranged perverts in the audience.

Adding to this air of cluelessness is the ultimate objective of the project: Ben and Andrew intend to make cinematic history with their contribution to Humpfest, a pornography festival, by calling their movie Beyond Gay. That's the "art" part of it, see: two men who aren't gay "boning" one another in a motel room. This priceless contribution to the world of film, moreover, will be executed at two days' notice and with negative production values. Such is the desperation of Ben's and Andrew's respective cases of Peter Pan-itis. What were they thinking? They were thinking that they would rather do anything than appear to be old and stuck and sensible. Until they discover, that is, that there is nothing that they would rather do less than — but it's so horrible that it can't even be named! — than to go there. (July 2009)

Copyright (c) 2009 Pourover Press