April 03, 2007

The Great Book Group Read of 2007

I've started group reads in the past, but without success, becaue I've asked too much of readers. A format in which I don't speak up until someone else has done so first was probably doomed to fail, at least as a start-up.

The real object of my latest experiment is to plow through some classic books that I haven't read. Better late than never! I'm beginning, however, with one that I have read, To the Lighthouse, simply because of its vernal atmosphere. I hope that someone who hasn't read it will join in, and make a wonderful discovery. I'm looking forward, though, to stumbling through books that I've heard about but never opened. There are two titles that strike fear into me: Don Quixote (because it rambles) and Moby-Dick (because it's thorny).

I have no idea how long it's going to take to get through any given book, so I've haven't devised a schedule. I would recommend acquiring each book when the previous book first comes under discussion. I don't know how often I'll post, either. More than once a week to be sure. As always, your comments will be most welcome.

The first entry will be posted on 9 April 2007.

The Great Books Group Read 0f 2007

To the Lighthouse

Don Quixote

Orley Farm

The American

War and Peace

The Sound and the Fury

The Decameron

Madame Bovary

Moby-Dick

Buddenbrooks

The Mill on the Floss

Fathers and Sons

Posted by pourover at 08:14 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 20, 2006

Black Mischief VI

The contraception pageant, catastrophically interrupted by traditionalist Azanians, is the major action of this chapter - just as any intelligent reader would foresee. Quite unexpected is the point of view from which it is witnessed. Waugh introduces two new characters, Dame Mildred Porch and Miss Sarah Tin, earnest leaders of the Dumb Chums Club, an animal-rights organization. The ladies have interrupted their return from South Africa to investigate Azanian horrors. They are indomitable types who get on by ignoring inconvenient facts and threatening to "tell the Foreign Office." They clearly prefer animals to human beings but have no idea why everyone wouldn't share this preference. Waugh has a lot of fun toasting them. The unsoundness of Dame Mildred is brought through when she writes to her husband,

I enclose cheque for another month's household expenses. The coal bill seemed surprisingly heavy in your last accounts. I hope that you are not letting the servants become extravagant in my absence. There is no need for the dining-room fire to be lit before luncheon at this time of year.

The letter is followed by diary entries that eloquently betray Dame Mildred's unbearable personality.

No news train. Wired legation again. Unhelpful answer. Fed doggies in market place. Children tried to take food from doggies. Greedy little wretches. Sarah still headache.

Presently the ladies arrive at Debra-Dowa, where they are shocked not to be put up at the Legation. Installed at Youkoumian's Hotel, they meet Basil Seal (Dame Mildred knows his mother), and note that he is...

Continue reading about Black Mischief at Portico.

Posted by pourover at 06:23 PM | Comments (1) | TrackBack

March 30, 2006

Black Mischief IV - V

It is no small measure of Waugh's ability to entertain that he can put off triggering his plot until the second half of Black Mischief. In Chapter Four, the final bits of setup are completed. Basil secures a seat on the train from Matodi to Debra-Dowa thanks to the willingness of Krikor Youkoumian to put his wife at mortal risk to make a buck. The train is to be a special train - the victorious Emperor is on board. This does not assure a prompt departure. "The Emperor has given no orders for a delay" must surely be one of the more bottomless wells of humor. After further displays of Azanian incompetence, the train proceeds to the capital, and, after an interlude at the Legations, the novel proceeds to the Victory Ball, at Prince Fyodor's night club, Perroquet. The ball, of course, is a perfect rout, Le tout Debra Dowa shows up, only to be poisoned by Prince Fyodor's bathtub champagne and ridiculed by the author. Basil is there, too, at General Conolly's table.

The Emperor had signified his intention of making an appearance some time during the evening. At the end of the ball-room a box had been improvised for him with bunting, pots of palm, and gilt cardboard. Soon after midnight he came. At a sign from Prince Fyodor the band stopped in the middle of the tune and struck up the national anthem. The dancing couples scuttled to the side of the ball-room; the guests at supper rose awkwardly to their feet, pushing their tables forward with a rattle of knives and glasses; there was a furtive self-conscious straightening of ties and removing of paper caps. Sir Samson Courteney alone absentmindedly retained his false nose. The royal entourage in frogged uniforms advanced down the polished floor; in their center, half a pace ahead, looking neither to right nor left, strode the Emperor in evening dress, white kid gloves, heavily starched linen, neat pearl studs, and jet-black face.

"Got up just as though he were going to sing Spirituals at a party," said Lady Courteney.

The racism that poisons Waugh's pen will make Black Mischief a difficult, if not impossible, read for tender souls, but I think that it's possible to get beyond it and enjoy the book's deeper satire, which has not race but planned economy (eg Communism) as its target. Then again, I'm not black. If it's any comfort, Waugh thought little better of Americans.

Continue reading about Black Mischief at Portico.

Posted by pourover at 04:36 PM | Comments (1) | TrackBack

March 28, 2006

The Little Foxes at CultureSpace

As readers of the Daily Blague know, I've discovered a very interesting new Web log, CultureSpace. It's written by MS Smith, and I'm linking to his site from here because he has written a fine entry about William Wyler's The Little Foxes (Goldwyn, 1941). I like to write about older movies every now and then, and I'd probably get to The Little Foxes eventually. It's a stunning picture, although Bette Davis often seems to be anticipating her role in The Virgin Queen (1955). Herbert Marshall, Teresa Wright, and Patricia Collinge are simply lovely.

But now I don't have to. Read MS Smith.

Posted by pourover at 03:32 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

February 02, 2006

The Four Readings of Emma

It was Ellen Moody, I believe, who told me about the Four Readings of Emma. The first time that you read this novel - especially if you're young - you identify with Emma; you share her complacency and then her disappointment and shame. When you read the novel a second time, knowing how full-of-it Emma can be, you laugh at her. The third time, you draw back a bit further, and see Emma as the people in her world might see her - if they were not so determined to admire her. You imagine, especially, how hurt Miss Bates must have been at Box Hill. This is the critical reading, in more ways than one; for it opens the way to the fourth reading, which compounds all of the above on a foundation of forgiving recognition. This is when you understand why Mr Knightley's love for Emma is almost as new as Emma's for him; until she was capable of adult contrition, she was only a child, and of no romantic interest.

Reading Emma for the sixth time, I'm astonished by the contrapuntal richness of approaching the novel on all these lines simultaneously. Few novels - few comedies, even - are so devoid of Important Event, but no novel illustrates more delicately the development of essential humility.

Posted by pourover at 02:50 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

January 31, 2006

Black Mischief: III

Two days later news of the battle of Ukaka was published in Europe. It made very little impression on the million or so Londoners who glanced down the columns of their papers that evening.

Thus Waugh takes us to London, the setting of Chapter Three. We overhear a broad spectrum of dismissive remarks. Then we're told that, "late in the afternoon," one Basil Seal reads the story at his club, which he has visited with the express purpose of cashing a bad check. Right at the start, Waugh calls into serious question Basil's status as a gentleman - the only status that really mattered to a man of Waugh's time and place. There is not a word in this chapter that is not complicit in Waugh's remarkable strategy of conducting his satire by means of elision and omission. In lieu of pontification, Waugh administers his critique in deadpan shocks that seem to acknowledge no system of morality whatever. The less-than-careful reader will conclude that the author is a nihilist, and it is this, rather than the occasional naughty situations, that gives Waugh's early novels their atmosphere of deep scandal. Never saying an untoward thing while making it impossible for the reader not to draw untoward inferences, Waugh titillates in the finest English going. The portrayal of Basil Seal embodies the technique. Basil can hardly open his mouth except to ....

Continue reading about Black Mischief at Portico.

Posted by pourover at 11:43 PM | Comments (1) | TrackBack

January 12, 2006

Black Mischief: II

Chapter Two of Black Mischief, considerably shorter than the first, takes us from the wilds of Azania deep into Waugh country. If Waugh is generous with his contempt for foreigners, it's hard to describe his feeling about the English. They're certainly very dangerous.

We are at the British embassy compound in Debra-Dowa. William and Prudence are dallying in the sunshine, exchanging desperately icy stabs at wit.

"Oh, dear, men are hard to keep amused." Prudence sat up and lit a cigarette. "I think your effeminate and undersexed," she said, "and I hate you."

"That's because you're too young to arouse serious emotion."

As indeed she is, still in her teens. Presently William and Prudence get back on their mule and head back to the Legation. Meanwhile, Waugh takes us on a tour d'horizon of the diplomatic establishment at Debra-Dowa. In addition to His Britannic Majesty's minister, there is the American Mr Schonbaum, whose interesting career the author traces, and the French M Ballon, about whom Waugh says no more than that he is a Freemason. Thus the stage is set for the presentation of one of Waugh's monumental incompetents, Sir Samson Courtenay.

As a very young man he had had great things predicted of him. He had passed his examinations with a series of papers of outstanding brilliance; he had powerful family connexions in the Foreign Office; but almost from the outset of his career it became apparent that he would disappoint expectations.

Sir Samson's problem - of which he is sublimely unaware - is an inability to pay attention to the things that matter. This, working with an inbred aristocrat's very peculiar priorities, renders Sir Samson deliciously oblivious...

Continue reading about Chapter Two of Black Mischief at Portico.

Posted by pourover at 08:00 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

December 30, 2005

Black Mischief: I

Quite aside from its other charms, Black Mischief will delight readers to whom political correctness has become burdensome. Although a converted Roman Catholic, Evelyn Waugh embraced contemptuous racial bigotry with pagan abandon. In fairness, it ought to be pointed out that he had contempt for almost everyone on earth; but he was always happy to make use of stereotypes if it would get a laugh. Embarrassingly, it usually still does, at least in the context of his monstrous farces. One little nugget will suffice: the Oxford-educated heir to an African empire whose throne, for the moment, is anything but secure, finds himself abandoned in a fortress.

Night and the fear of darkness. In his room at the top of the old fort Seth lay awake and alone, his eyes wild with the inherited terror of the jungle, desperate with the acquired loneliness of civilisation.

And that's a fairly mild example. The "inherited terror" is meant quite seriously; Waugh believed in a kind of debased Darwinism, according to which we are who we were. If our ancestors responded to the nocturnal crashings-about of predators with exophthalmic anxiety, then so will we. Waugh is kind enough to allow Oxford to make its contribution to the Emperor's discomfort.

Black Mischief takes place on an imaginary island in the Indian Ocean, not far from either Somalia or Aden, formerly known as Sakuyu, but now the Empire of Azania...

Continue reading about Chapter One of Black Mischief at Portico.

Posted by pourover at 12:00 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

November 28, 2005

Tosca

Sooner or later, every opera fan learns that critic Joseph Kerman, in his 1956 book, Opera as Drama, denounced Giacomo Puccini's Tosca as a "shabby little shocker." The "shabby" owes, I think, to the slapdash performance practice that obtained with respect to Puccini's operas until well into the Seventies. (I still remember being blown away by Zubin Mehta's Turandot, which presented Puccini as orchestrally interesting.) Listening to the opera on Saturday, I was struck by a string of reminiscences of Mahler's "Resurrection" Symphony, of all things; the score of Tosca, while not the most scrupulous composition in opera land, is anything but shabby.

As for "shocker," well, Tosca can still shock. Its three deaths all horrific. First, the malignant Scarpia, bloated with lust, turns to meet the nasty surprise of Tosca's blade; he may deserve what he gets, but you feel his bewildered terror. Then Cavaradossi is shot by the firing squad. You may at first believe, with Tosca, that the bullets were blanks, and that the painter will rise up as soon as the soldiers troop off. But I don't think that you can have been paying very close attention to this opera if you arrive at Act III with optimistic expectations. Cavaradossi dies twice, in effect - for the second time when Tosca discovers the truth. And, finally, there is her heroic suicide, jumping to her death from atop the Castel Sant'Angelo. These endings are enduringly arresting.

And then of course there's Tosca's pantomime after Scarpia's death, arranging the candlesticks and crucifix about his corpse before leaving his plus apartment in the Palazzo Farnese. This is the heart of the opera, and if no one is singing, that's because there is so much that is simply unspeakable about this story. The French playwright Victorien Sardou, who wrote La Tosca for Sarah Bernhardt, claimed to have found the kernel of his story in an episode from the French religious wars of the sixteenth century; thank heaven we were spared yet another one of those. Set instead in the Rome of 1800, amid the Napoleonic Wars, Tosca is unusually stylish. But regardless of the setting, Tosca is about the mercilessness of unbridled state power. Without that, there would be no story.

Scarpia is an unusual villain for opera in that he combines two strands of villainy that usually work alone. The first is the obsessive who will stop at nothing in the pursuit of his object, which is usually the death of somebody else. The second is the representative of authority who is only doing what he's supposed to do. To this coupliing Scarpia brings a sadism that is almost his alone. He persecutes Cavaradossi as much out of jealousy as out of zealotry. No one is safe in Scarpia's world. Tosca is far more political than it claims to be.

Although Act I meanders a bit, especially before the arrival of Floria Tosca, it compensates for its lack of a dramatic death with a finale of voluptuous blasphemy, as Scarpia bellows over the choral Te Deum that Tosca makes him forget God Himself. Overall, Tosca is too short to wear out its welcome. The operas that Puccini would write after Tosca, and before Turandot - the opera in which he returned to the old style composition of "numbers" - all suffer from a combination of length and shapelessness; Puccini, like it or not, is the musical ancestor of Andrew Lloyd Webber, Alain Boublil, Claude-Michel Schönberg, and other creators of today's formless and forgetful confections. Only in Turandot (which he did not live to complete) would Puccini rediscover the powers of great tunes and taut forms.

Posted by pourover at 07:08 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

November 23, 2005

Don Carlo

Don Carlo, the first of Verdi's great and final four operas, was, like his other grand grand opera, Les vêpres siciliennes, written for Paris. Left to his own devices, Verdi preferred concision, happily dispensing with ballets and crowd scenes. You can see this in Aida, which, while it is just as grand as Don Carlos, is much more concentrated. It is also shorter. Both operas have their big triumphal marches (sort of), but the link between Nubian freedom and Aida's betrayal is much tighter than the connection between Flemish freedom and Isabella's proscription. Grand opera, in Paris, required plenty of sub-plot, and was in no hurry to get anywhere. Don Carlo remains Verdi's most upholstered opera.

Efforts to trim it down, by omitting the entire First Act, are misguided. Whether Verdi was impatient with it or not, the ecstasy of newfound love is what draws us into this complicated tale. Like Carlo and Isabella, we spend the rest of the opera remembering this moment of exultation, so cruelly cut off when diplomats decide that the French mistress will marry, not the Spanish prince, but the Spanish king. The suddenly-banked passion illuminates the entire opera, as Carlo and Isabella remain on painfully honorable terms while giving rise to doubt in the bosom of Philip II. When they call one another "madre" and "figlio," it's heartbreaking; what they really want to say is "amor."

Don Carlo pits the individual against the institutional, with Old-World results. Affairs of state and the interests of the Church invariably prevail. Struggling against them looks noble, thanks to Verdi's treatment, but it is fundamentally quixotic, and that, too, is registered in the score's representation of oppressive grandeur. (Note that I speak of its "representation". The score itself is not oppressively grand.) Who can battle the schizophrenic counterpoint, between joyous acclamation and death march, of the huge scene that concludes Act III, at the cathedral doors? Verdi makes no bones about his anti-clerical sentiment, but it must not be forgotten that it's a monk who snatches Carlo from the jaws of destruction at the end. Everyone here is trapped, and the better you know this opera the better you understand its knack for turning what ought to be a heroic art form dominated by great actions is really a sequence of ambered beads. The heroism is all in the music.

There are no small scenes in Don Carlo, not even the Garden Scene that opens Act III, with its cast of three. Destiny looms everywhere, and, to a great extent, it is determined by birth. Verdi's kings and queens appeal to us because they express the constraints of royalty, the lack of freedom to follow their hearts' desire. Encased in luxury, they are wretched and lonely. Never has this been shown to better effect than in the king's great aria, by turns meditative and roaring with pain, "Ella giammai m'amò" ("She never loved me" - as of course she couldn't, as she had already fallen in love with his son.) As soon as he's finished, the creepy, blind Grand Inquisitor is shuffled in, and the two egos battle their way up the scale in mounting tension that bursts when the old priest reminds the king that God the Father sacrificed his son! As if that weren't enough, Isabella rushes in and demands justice - her jewels have been stolen. This little problem is worked out at the cost of a great courtesan's freedom, and the scene ends with the justly celebrated "O don fatale" ("Oh fatal gift" - Princess Eboli refers to her own beauty). All this in just one scene! And if it is historically implausible - such freedom of expression in royal precincts would not have been countenanced in sixteenth-century Spain - it is psychologically riveting. There is not a character in it who doesn't absorb our identification.

There is a fair amount of gloomy music in Don Carlo, and it comes at bad times - at the beginning of scenes. There is a long political discussion that may not hold your attention. My advice is to let your mind wander whenever the music doesn't pull you in. Don't feel guilty, or that you're not getting it. You're coming to Don Carlo from the raucous immediacies of the early twenty-first century. Submit to the territory that claims you, and wait for the rest to earn your allegiance. It's no crime if parts of it never do. Don Carlo is truly a whale of an opera.

Posted by pourover at 05:17 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

November 20, 2005

Die Zauberflöte

Die Zauberflöte (The Magic Flute) is the last of Mozart's Famous Five, a series of operas that sandwiches the three most divine Italian operas (even if Italians don't think so) with two German singspielen. The Great Seven frame the Famous Five further with two very fine opera seria, thoroughly conventional dramas, set to themes from classical antiquity (one mythical, one historical). So Zauberflöte is not Mozart's last opera. Although La Clemenza di Tito (The Clemency of Emperor Titus) opened three weeks before The Magic Flute, and not even in Vienna, but in far-off Frankfurt, it was composed afterward. It is my conviction that the hectic rush surrounding these premieres irreversibly compromised Mozart's health, killing him a little over two months later.

Die Zauberflöte is like nothing else in Mozart's oeuvre. For all the mumbo-jumbo of its Masonic references (which I take no more seriously than I would if a magpie had assembled them), this is by far the most accessible of Mozart's operas. It is so much more accessible, in fact, that it makes a lousy introduction to Mozart's operas in general. Its tunes pack a memorability punch that is rarely encountered outside of Verdi. There are no complex ensembles; the beautiful "locked" quintet, early in the first act, is a big bunch of silliness that works better in a language that you don't understand. Certainly nothing beyond an exchange of bromides occurs during it. Much the same can be said of the corresponding quintet in the second act (for the same voices). The music seems to be beautiful not for any dramatic purpose but simply for offering the pleasure of beautiful music.

Come to think of it, that describes every note in this piece of puppet-show nonsense. Pairing the noble prince, Tamino, with the peasant birdcatcher, Papageno, is an almost senseless deviation from the usual operatic male coupling of the period (think Don Giovanni and Leporello), for Papageno has nothing to offer but liability. In a bizarre correspondence, his mate, Papagena, comes into the action altogether too late to form a partnership with her natural mistress, the noble princess, Pamina, who is forced to go through the action in singularly isolated fashion - this is what makes her huge but simple aria of despair, "Ach, ich fuhl's" so moving. The roles of the Queen of the Night and Sarastro are totally confused, but even in this they fail to hang together. The Queen is a coloratura showoff whose music can't really be sung by the human voice, while Sarastro, in single-minded masculine fashion, seems interested only in showing off the, er, depth of his voice. Conventions aren't flouted so much as upended.

There is only one way in which The Magic Flute makes sense, and, happily, it has been doing so to thousands of audiences for over two hundred years. It is play. It's Amadé in his toybox, making an Olympian racket. You can get analytical if you want to: Sarastro is the father Mozart wished he'd had; the Queen of the Night is the father he'd been stuck with. Und so weiter. But just remember that that's your toybox.

In any case, take the kids. Play it for them, at least. Have it on in the background. And be sure to tell them the story of an opening night when Mozart was actually backstage. Emanuel Schikaneder, the Viennese impresario who commissioned the entertainment and the first Papageno, couldn't have played his character's magic bells to save his life, so a musician backstage was posted to accompany Schikaneder's mime. On one occasion, Mozart is said to have taken over the glockenspiel during "Ein Mädchen oder Weibchen" and made a point of striking notes when Schikaneder, onstage and in full view of the audience, conspicuously wasn't. It was the most glorious kind of childishness. So is Die Zauberflöte.

Posted by pourover at 10:42 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

November 09, 2005

Ariadne auf Naxos

The composition of Ariadne auf Naxos, the third product of the collaboration between composer Richard Strauss and poet Hugo von Hofmannsthal, was a weird and winding affair that straddled World War I. I don't propose to untangle it here, but only to suggest that the opera's unparalleled sheen of sophistication may owe to its two coats of "finished."

The first version of the opera, staged in 1912, came at the end of a performance of Der Bürger als Edelmann, a translation of Molière's Le bourgeois gentilhomme. Good students will recall that the fifth act of this play is a sort of burlesque, or a roast, of which M Jourdain is the happy victim. At the instigation of Max Reinhardt, Strauss and Hofmannsthal came up with a short period opera to replace the burlesque. Two operas, actually: an opera seria, on the theme of Ariadne's abandonment by Theseus on the island of Naxos, and her apotheosis in the arms of Bacchus, would be interrupted by a cheeky opera buffa featuring commedia dell'arte characters. As such, this version of Ariadne was a mixed-media affair. First the play, with incidental music, and then the opera.

The second version of Ariadne, premiered in 1917, replaced the Molière with a "Prologue" that would set up the fanciful juxtapositions of the "opera." Set behind an impromptu stage at the home of the richest man in Vienna, circa 1690, the Prologue pits the composer of the opera seria and the dance master behind the opera buffa against the millionaire's major-domo. The major domo astonishes the company with a bizarre pronouncement. In view of the length of the planned entertainment (first the opera seria, then the buffa) and of the opera seria's setting on a depressing desert island, and, finally, of his own impatience for the fireworks display - in view of all this, the richest man in Vienna has decided that the two musical works will take place simultaneously.

The composer refuses to allow his work to be compromised; he is far too high-minded to permit his melodies to mingle with vulgar ditties. Will the show go on? Strauss and Hofmannsthal decided to cast the Composer as a travesti, contralto role, much like Octavian in their preceding collaboration. Like Octavian, the Composer burns with a youthful ardor that is still somewhat immature. Whatever the extent to which the creators of this work intended us to laugh at the anachronism of a seventeenth-century composer's claiming the sanctity of art work, I believe that uncertainty on this and other points is the beauty of Ariadne auf Naxos itself. (The music is beautiful too, of course.) The opera never establishes itself "in period." Our sense of the nature of what we're watching flickers. Now it is a neoclassical composition, an homage to Rameau and Couperin. Now it is a late Romantic work tricked out with perrukes. In the end, it is both at once. Take an opera by Handel. Then imagine what it would be like if Wagner rethought it. Then imagine what it would be like if a Wagner with a sense of humor rethought it. Now you have Ariadne auf Naxos.

The show goes on - of course it does. I ought to say here that Ariadne is far more difficult to explain than it is to watch. Thanks to the Prologue, the funny business in the Opera is expected. Nor is the music unusual on its surface. It becomes strange only to the degree that it fails to correspond to its models, or, rather, to the degree that it raises the question of just what, exactly, its models might be. Strauss scores the opera for a "period" orchestra, one with far fewer strings than was normal in 1912. He employs a harmonium to take the place of the organ in backing up the serious recitatives, while a piano replaces the harpsichord. The effect is not reminiscent of Mozart or Bach, but it does suggest the bygone fashions of a parallel universe. It is a chamber opera most of the time, but a chamber opera with Alzo sprach Zarathustra propensities. Of the principal singing roles, two, Bacchus and Ariadne, seem to have dropped in from Bayreuth between Rings. Two others, The Composer and Zerbinetta (she heads the buffa team), are of Mozartean descent. The irony of reference and the sophistication of allusion, while invitingly good-humored, are intense.

However "meta" all of this might seem, Ariadne auf Naxos is planted firmly in the soil of tradition. In his portrayal of the abandoned queen, Strauss lays out an idea of the use of classical subjects that covers all the arts; it is impossible not to think, for example, of Titian's great picture at the National Gallery in London. The commedia dell' arte passages endearing updates that stay very true to the spirit of their venerable form of entertainment. The seduction of the Composer in the Prologue is another Straussian transformation of a Mozart original. Even though Ariadne refuses to settle down, it is always very much at home.

Posted by pourover at 05:30 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

October 31, 2005

Lohengrin

For many years, Lohengrin, or what little I knew of it, was a hideous mothballed souvenir of Victorian bad taste. It wasn't the silly story or the medieval setting but the earnest piety of the nineteenth-century. By the time I was twenty, Lohengrin had become a scapegoat, loaded down with the essence of threadbare sentimentality. I had come to music from Mozart and the baroque. Can the argument be made that you can't get further from Vivaldi than Lohengrin?

Ah, the energies that we invest in our youthful dislikes. The joy of disliking what we don't really know anything about! It's the cheapest form of self-definition going.

Eventually, I realized that my dislike of Lohengrin was very old baggage, that ought to be unpacked or discarded. It was the only Wagner opera (aside from Der fliegende Holländer, which still hasn't caught my ear) that I didn't know and like. I decided that I would just listen to it.

It was still pretty Victorian, but enough about me. (Here is a synopsis.)

I find it difficult to write about the music of Richard Wagner. The music itself. Wagner's sense of form was unique. Where other composers assemble the elements of music in discernible structures, Wagner fashions complex molecules that resist analysis. His ideas about "what comes next" struck many contemporaries as simply insane - insane, but effective. There is not a film score today that does not have its origins in Wagner's mastery of controlled abandon. He knew what he was doing, but he had no interest in laying out puzzles for his audience to solve. He seduced his audience into giving up thinking altogether, and simply feeling. Wagner manifests what Plato feared about music - that it could have an irrational purchase on the soul.

Where did Wagner come from. As far as I know, he was the first master composer who didn't do something else musical first. He was no instrumental virtuoso, and thinking about this reminds me that every innovator from Bach to Schumann was a keyboard virtuoso. Wagner erupted fully formed, or so it seems if you limit you attention to the operas that still hold the state. In fact, he rather spluttered, with lots of missteps and forgettable compositions along the way (although I am very fond of the neglected Symphony in C). There is no doubt that he learned much from Beethoven, but in a sort of remix way. Beethoven wasn't teaching the things that Wagner learned from him. Beethoven was one of those "wild men" who is really quite fastidious and conservative. He would never have dared to go where Wagner went, giving musical expression to Eros.

That is what is different about Wagner. Hitherto, love had been rather politely represented. It had worked much better as a sorrow than as a reward, sorrow lent itself to eloquence, while the expression of contentment had to be geared for "family" audiences, and it tended to sound inane. Nobody had the nerve to put the real delights of love - all of them - into music. Throwing out the sonata form, Wagner replaced it with another, one traced from the ebb and flow of assurance and satisfaction that that inflects desire, physical and otherwise.

And then he did something else, and I really don't know quite how to describe it. In the classical style, which prizes balance and lucidity, the themes of symphonic music are distributed evenly throughout the orchestra. That's the idea. Aside from the odd trumpet or horn call, classical music spreads its counterpoint through a band whose violins are almost always going and whose other instruments provide decorous coloration. With Wagner, the dominance of the orchestra by strings comes to an end. They sit mute while the show moves to the brass. Or the brass may drown them out. By Parsifal, Wagner was writing scores that passed insensibly from crashing declamation to chamber music. Well, that's how love be some time.

One consequence of Wagner's innovation is that operas lasting hours fly by much faster that extracts. Götterdämmerung hurtles along like an asteroid aimed at Planet Earth, but, to my ears anyway, "Siegried's Rhine Journey" and the "Death March" always seem to go on forever when played by themselves. Amputated, they may retain some of their original beauty but none of their life. You can't try to take Wagner's music apart. You can break up the drama into scenes, and so forth, but the operatic Act - Wagner's basic unit of composition - has to be taken entire, and this poses a problem for anybody who wants to write about it without spreading scores all over the floor.

Lohengrin is the last of Wagner's operas, however, to exhibit remnants of the traditional, "number-based" operatic style that began, centuries earlier, as a chain of arias separated by filler. It is the last to allow the strings to prevail. It is not as conventional as it may at first sound, but it seems different from Das Rheingold, Wagner's next work and the first member of the Ring cycle, in a profound was, almost as if the composers of each opera were a father and son team, and not the same man. Wagner takes a certain amount of trouble to be formally coherent - and it gets in the way, here and there, of emotional coherence. The action seems fussy and overheated. That the knight who stands up for Elsa in the first act can't reveal his name seems hokey, because Wagner still doesn't know how to persuade us that such mysteries might be real. (He will learn very fast.) Elsa herself is the most pallid of Wagner's heroines, too maidenly by half. The only time that Elsa shows any real spunk, it's because she's concerned about the nobility of her new husband; she brings everything down upon her head by demanding to know what his family connections are. She is always upstaged by the evil Otrud.

Where Elsa shines is in the ensembles, and there are two fantastic ones in Lohengrin. An ensemble is a passage for three or more singers in which the musicians not only have different lines to sing but different things to say. The only way to appreciate an ensemble is to sit down with the libretto and read it through. (Subtitles can't begin to cope - perhaps the principal shortcoming of DVD opera recordings.) Once you have a general idea of what each character is saying, the music will come to life - and you can forget the words. But remember this: the staggering conceit of the ensemble is that none of the characters who are singing their heads off can hear what the others are saying. Dramatic irony, in other words, is a staple ingredient of most ensembles. From Mozart on, most operatic acts end in ensembles, usually with chorus. This, too, would be a convention that Wagner would drop. But not quite yet.

Wagner has composed Lohengrin's ensembles in such a way that Ortrud is usually inaudible, while Elsa's voice gleams innocently at the top. That's why I recommend learning the ensembles of Lohengrin first, instead of beginning at the beginning. (And what a beginning it is, with all that boilerplate from the King.) Turn to the end of the first act, where the King says a prayer before Lohengrin and Telramund do battle. When the King is through, the other principals comment on their feelings, all at once, and presently the chorus takes up the prayer, which rises to a glorious climax. The other ensemble, at the end of Act II, occupies nearly half that act's performance time. It was originally planned as a simple wedding procession, but Wagner opened it up with outbursts from Ortrud and Telramund. The outbursts are solos, but the responses are contrapuntal - that is, in ensemble form. "Monumental" would be the word. Get to know these, and you will encounter most of the opera's thematic material. You will also be roused.

Posted by pourover at 03:27 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

October 17, 2005

Un ballo in maschera

Un ballo in maschera (A Masked Ball) is perhaps the most insistently tuneful of Giuseppe Verdi's thirty operas. Written in 1859, it is the last opera that Verdi would write in a traditional style, with numerous free-standing arias. There is a lighthearted feel to it that would not reappear in Verdi's work until the composer's last opera, Falstaff, in 1893 - and then in rather more complex form. I think it's impossible not to like Ballo.

Balls and other entertainments figure in many Verdi operas, and I for one love his party music. It's deeply silly, really, in the way that Rossini's overtures are deeply silly. At least they are to me; a number of my opera-fan friends find it simply boring, because nobody's singing. When, as is more usual, someone is singing, they don't notice in the background. I adore its divinely exuberant nonsense. Can you imagine Verdi doing the polka? No, neither can I. When he writes one, he lets you know exactly what he thinks of such activity.

In Ballo, the party comes at the end. There's the big chorus with which these scenes usually begin, and then some other dances while the conspirators and Renato try to isolate Riccardo. But when the hero and Amelia fall into conversation - he wants to talk about her, she wants to get him to leave while he's still alive - there's a lovely little number in triple time, more minuet than waltz, played by a violin and a bass. It's wistful and archaic and very intimate; the ball seems to have moved elsewhere for the moment. When it comes to its faltering end, Riccardo does not have much time left here below.

As is usually the case in a Verdi opera, we have lovers who cannot be together. In this case, that's because one of them, Amelia, is married to the other's - Riccardo's - most trusted minister. It is also the case that one of the lovers is a royal. Originally named "Gustavo," after Gustavus III of Sweden, the hero had his named change when a foiled bomb attack didn't kill its intended victims, Napoléon III or Eugénie, but had a chilling effect on dramas involving the assassination of heads of state. So Ballo was moved to pre-Revolutionary Boston, where as the Earl of Warwick Riccardo served as governor. Recent productions have restored the Swedish setting but left the principal names as altered, and they've also failed to get round one of Riccardo's last lines, "Addio, diletto America!" ("Goodbye, delightful America!")

Technically a three-act opera with several scenes, Ballo has always seemed to me to be a five-act work. The first act is mostly fun, with the ominous background of baritonal grumbling along conspiratorial lines. The second act opens with enormous, stark drama, very suitable to a "witch's cave." Riccardo has dropped in, dressed as a sailor (he sings a jolly barcarolle), to see whether Ulrica's prophecies are harmful and worthy of prosecution. As an enlightened skeptic, he's inclined to let her continue unhindered, even after she foretells his death by the hand of the next man to shake his hand. He laughs this off in a dazzling ensemble piece, "E scherzo od è follia." Whenever Riccardo steps forward, the mood brightens considerably. Then something else happens, in this case Renato's appearance on the scene. Of course Renato immediately shakes hands with his boss.

The third act is ve-ry spoo-ky, and great fun because of it. Amelia has ventured out onto the heath in search of an herb that Ulrica has promised her will, if plucked at midnight, cure her of her passion for the man she cannot love. Instead, she finds Riccardo himself - he overheard her in the previous act. After a slam-bang love duet that provides a minitext on What Opera Is All About, complications set in, and the couple is discovered by Renato. Oh-oh. In the brief fourth act, which takes place chez Renato, Renato joins the conspirators and forces his wife to draw the name of Riccardo's assassin from a vase. Riccardo's secretary, Oscar, shows up with the invitation to a magnificent masked ball. The irony is thick enough to choke the unwary.

The final act opens before the curtain, as it were. Riccardo is alone, but that doesn't stop him from soliloquizing about his plan to send Renato (and Amelia) back to England. In true opera-hero fashion, he sings of this move that he can hardly bring himself to think about, and assures us of his resolution to carry it out. Verdi is the past-master of love denied out of duty. Did I say that the lovers are technically innocent? There was that embrace on the heath, but nothing more. Even so, Amelia's virtue has been compromised in her husband's stern eyes, and his honor can be avenged in only one way. Of course, the minute he stabs Riccardo, he comes to his senses and is horribly sorry. With his dying breath, Riccardo forgives everybody. Once he's dead, Verdi is free to end the opera with crashingly dismal chords.

But musically this opera is - I've already said it ten times - great fun.

Posted by pourover at 07:32 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

October 08, 2005

Don Giovanni

Don Giovanni, the second of three collaborations between Wolfgang Amadé Mozart and Lorenzo da Ponte, is a revolutionary opera, in that it transformed opera itself. Always an ambiguous drama, the story of Don Juan had been entertaining audiences since the early seventeenth century, but it was not until 1787 that the story was given a musical treatment that fully realized its possibilities. Listening to it the other day, I saw for the first time how this was accomplished.

Don Giovanni will never be my favorite Mozart opera, and I suppose that that makes it easier for me to assess its glories. I'm not drawn to the story, which is too cynical and nocturnal for my taste, and none of the characters really appeals - as do, say, the Countess and Susanna, and even the Count, in Le Nozze di Figaro. These objections, however, are vaporized by Mozart's music, which pulls off the astounding trick of recognizing the essentially comic nature of the plot while honoring each character's sincerity. Fundamentally a bedroom farce with a surprise ending, Don Giovanni is stocked with characters who betray their commedia dell'arte ancestry: the young rogue, his back-talking (but ultimately weak-kneed) valet, the foolish older man, the ineffectual ninny, the pastoral louts, and some silly women. The aristocrats in the group take themselves very seriously, and Mozart realizes this seriousness in music. He provides da Ponte's characters with a score that, far from ridiculing them, takes their self-esteem seriously. At the very same time, this music never lets us forget that we are watching something that's supposed to be funny.

The first Viennese audiences didn't find Don Giovanni funny at all, so don't feel bad if the humor doesn't hit you immediately. The other day, though, it hit me early on, in Donna Anna's duet with Don Ottavio. The lady's father has just been killed in a duel - by Don Giovanni, of course, defending himself against the old man's attempt to avenge his daughter's alleged dishonor. Don Ottavio, who would like to be Donna Anna's boyfriend, offers to replace the lady's father while serving as her love interest as well -

Hai sposo e padre in me. (In me you have both husband and father.)

Did you ever hear anything so preposterous? I mean, really. That's how da Ponte is, by the way; he has an unparalleled knack for adorning heroic sentiment with preposterous plumage. The music is heroic when, a few bars later, Don Ottavio swears to avenge the Commendatore's death, but "Hai sposo e padre in me" has already made a fool of him dramatically, and a fool he remains for the rest of the opera - a real capon. Mozart staples Ottavio's sincerity to his silliness: you see that he's a fool, but you know what he's feeling. As for Donna Anna, she makes a fool of herself as well a bit later on, when, having recognized Don Giovanni in a different setting, she relates to Don Ottavio (who is always by her side) the scene of near seduction that led to her father's death, and then sings a grand aria about the vital importance of her own honor in which Mozart repeats the stapling stunt.

This duet - an accompanied recitative, technically - would serve Italian opera as a model for the dramatic moment; in its shifts, its sequence of moods, we can foresee such great confrontations as the father-daughter scene in Act III of Aida. It would take Verdi, however, to scrape away the mockery of grandeur that's inherent in the model. When I listen to operas by Donizetti and Bellini, I'm charmed by their composers' profound unconsciousness of the beautiful fatuity that they have learned from Don Giovanni. I am pretty sure, however, that Rossini was aware of it. His entire later career was a celebration of beautiful fatuity. But I digress.

There's a difference between mockery and ridicule. You mock a self-important person by laughing at his self-importance; you ridicule him by denying that he has any reason to be self-important in the first place. Leporello mocks his master nearly all the way through, but he never even attempts to ridicule him. He laughs at Don Giovanni's vices and foibles, but he does not belittle their victim.

Even when the libertine is finally dragged off to hell, the music is not without its winks. I'm thinking of the rising scales that accompany the Stone Guest's exhortations, and of a few other details too slight to mention outside the context of a running commentary to the music. I'm also thinking of the Requiem, in which Mozart paints hell and its torments in tones that are dead serious, without a hint of the facetiousness that sparkles on every page of Don Giovanni.

As always, I urge listeners to take the drama of Mozart's opera at face value, and not to indulge in theories about Giovanni's sexuality or Anna's hysteria. It is fun to follow writers such as Brigid Brophy into interpretive thickets, but ultimately, I think, unnecessary. The tension between text and music, and between the melodies and their often sarcastic accompaniments, is not meant to be resolved; the "mystery" of Don Giovanni is nothing but a miracle, and miracles are by definition meant to be witnessed but not comprehended. I suspect that one might analyze the score so thoroughly that the semiotics of Mozart's ambiguity were laid bare, but that would be rather like analyzing a joke. One would be the poorer for the effort.

Posted by pourover at 06:38 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

September 22, 2005

Der Rosenkavalier

There are times when I worry that Der Rosenkavalier has told me everything that it has to say. The attraction that drew me to it when I was a young man was very strong, and it had a meteorite-sized impact on my erotic life. It taught me about a kind of love that I should never have discovered on my own, a kind of love that, as I approach old age, seems truly wonderful to me. A little German to the rescue: a love not wunderbar, but wunderlich. I should have had a much better-ordered, less distracted youth if this idea of love as a consequence of carnal desire had never crossed my mind. In other words, Der Rosenkavalier is the dirtiest opera ever. I want to talk about its dirtiest part, which is its first act. While I was listening to it on Saturday, it struck me as perfectly fresh.

How can I put the plot of this big opera, which I have no intention of exhausting all at once, into two sentences? There are four principals: a seventeen year-old boy, new to (actual) love, who can't believe his success in landing the attentions of a very grand and sophisticated older woman (all of thirty-two) who on her part has the bad luck to be related to a very vulgar country cousin who's need of a young man to officiate at some aristocratic formalities with his teenaged fiancée (the bumpkin's). The older woman nominates her young lover as the man to do the honors - a move that looks more reckless every time I experience this opera; for, when the young man presents the ceremonial rose to the fiancée, love takes turn that, while unexpected by the characters on stage, couldn't possibly be more eagerly anticipated by the audience. In the end, the sophisticated lady and the rube (no longer on speaking terms) are standing alone.

What came to me on Saturday was that Hugo von Hofmannsthal, the librettist, knew his eighteenth century even better than I'd thought he did. He understood that his play was set in an age of new discovery. The new discovery was something that I wrote about the other day, if in passing: the idea that, for the final touches of their education, men ought to submit to women. That women are the transmitters of civilization. Not men. That men don't care enough about succeeding generations. That men are too wrapped up in themselves. That men. immersed in the moment, are disinclined to pay attention to the things that might turn out to be important later.

The first act of Der Rosenkavalier, which so strikingly has its own three-act structure, is, among other things, about how the Marschallin ("field marshal's wife" - the thirty-two year-old lady) teaches Octavian, who is still "ein bub," his manners. And beyond all the little lessons that she conveys is the insistent one that he pay attention. It isn't that an older woman teaches a younger man about love. It's that a woman teaches a man how to behave. That's what changed for me on Saturday, the difference between those two sentences. The older-younger detail, so crucial to our ideas of teaching, is unimportant.

The structure of the first act is a-b-a. In the outer parts, the Marschallin and Octavian are the only singers on stage, and the setting, although not the mood, is intimate. The mood actually changes rather a lot. The central section is a crowd scene to rival Act II of La Boheme, a levée in which the Marschallin receives petitioners or clients - people who seek her influence or protection, or who simply want her to buy something. A hairdresser gets her ready for the day while a flutist and a tenor audition their act. The scene begins when Baron Ochs, the Marschallin's cousin, barges into her bedroom unannounced, and it ends with his withdrawal. It is all very bustling and 'period,' such that it might invite us to regard the flanking scenes as timeless. Certainly love is timeless, but the texture of the lovers' encounter is no less wrapped up in eighteenth-century specifics than the "spies" who try to interest the Marschallin in their scandal sheet.

While the Marschallin is obviously quite satisfied with Octavian's sexual prowess, her love for him seems to have more to do with making him less of a self-absorbed teenager. His solipsism charms her, but only insofar as she can fix it. He throws a little fit when she chides him for leaving his sword in plain sight in her bedroom. She has to calm his jealousy when, in a moment of preoccupation, she hints at having nearly been caught by her husband in flagrante. When he gushes that she must have been terrified on his behalf by the Baron's interest in the lady's maid that he pretended to be during the levée, she replies drily, "Ein bissel, vielleicht." ("A little, perhaps.") But when Octavian insults her with the charge of "talking like a priest" and denying him kisses until she's on her deathbed, she momentarily withdraws her affection and dismisses him, an act she immediately regrets. Their cause of their little tiff is the issue at the heart of the opera: love - their love, certainly - is transitory, and a day will come when it ends. Octavian, flushed with the joys of first love, can't bear to hear this; it is an insult. He's going to be different. (When I first got to know this opera, I vowed that I was going to be different, too.) By the next time that he sees the Marschallin, he has discovered a deeper love for someone else.

But that's in Act III. We'll talk about Acts II and III some other time.

Posted by pourover at 05:26 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

September 12, 2005

La finta giardiniera

Listening to Mozart's La finta giardiniera on Saturday afternoon, I was wondering what actually - musically - distinguishes it from the composer's mature operas. Palpable as the overall difference was, I couldn't come up with anything that wasn't simply quantitative. The later operas are bolder, quicker to make their points. The orchestrations (thanks to Mozart's discovery of the clarinet) are richer, less likely to plant a tune among the violins. The modulations are more subtle and expert. The later Mozart is older and wiser. The later operas ought to be better.

Then it occurred to me that a listener who didn't care for Mozart (PPOQ, for example) might not discern any difference at all. This thought stopped me in my tracks.

Written for Munich in 1775, when Mozart was nineteen, La finta giardiniera utilizes a libretto that had enjoyed a great success at Rome the year before. Isn't that curious, that eighteenth-century habit of having new composers write the music for old librettos? It's as though Oscar Hammerstein's lyrics were reset first by Stephen Sondheim and then by Mel Brooks. Mozart's version had three performances, and then dropped out of sight for over a century. (As a German singspiel, Die Gärtnerin aus Liebe, it had a sort of afterlife.) The plot is stylish but silly, and I won't detain you with it here. The arias are unfailingly lovely, but as a series of carefully articulated moods, the opera makes an overall impression that's more reminiscent of Handel operas that Mozart never would have heard than it is of the great works to come. The recitatives are already interesting, but they're not yet arresting,almost instantly memorable, as they will become in ten years. At the end, however, there is a wonderful scene that anticipates the duets, whether between the sisters or between Ferrando and Fiordiligi, of Così fan tutte. It's a lovely reward for having listened to three pretty but unspectacular acts.

In the end, the problem with La finta giardiniera is that Mozart wrote it. Were it the work of any contemporary, it would be immensely interesting. Miraculous, even. But because it's obviously Mozart's work and yet not at all sublime, we're disappointed. It's perverse, but understandable. But it's no reason not to give the opera an airing once every couple of years.

The Teldec/Das Alte Werk recording in my library is still available, but pricey. Unfortunately, the Philips recordings have been allowed to lapse.

Posted by pourover at 03:55 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

August 05, 2005

The Devils of Loudun

Undoubtedly, The Devils of Loudun owed something of its réclame to its "interdisciplinary" construction. It is a history book that can't be bothered with dates. It is a work of completely undocumented sociology, backed up by Huxley's credit alone. It is a non-fiction novel that also expounds metaphysical philosophies. If I neglect to mention demonic possession, that's only because the author doesn't believe that it actually occurred. He doesn't to believe that there was ever any good reason to believe that it occurred. It's the fact that the case for possession was able to proceed without solid evidence that interests him. I believe that the book is going to be reissued this fall, but only in England. I wonder what sort of an impression it will make, if any.

In the summer of 1634, Urbain Grandier, a Jesuit-trained parish priest, was burned in the town of Loudun for having arranged the demonic possession of a convent of Ursuline nuns.

Continue reading about The Devils of Loudun at Portico.

Posted by pourover at 12:00 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

July 07, 2005

Decline and Fall

The first time that I read Decline and Fall (1928), I didn't get it. Still in high school, I wasn't nearly sophisticated enough to appreciate its deadpan satire. I didn't know enough about England, and I didn't know enough about nonsense. My idea of funny writing was Robert Benchley's output. I thought that funny writing ought to be fun, and Decline and Fall, while wicked and laughter-inducing, is not fun. It is at heart among the most serious of books, as are all of Waugh's great novels.

The title might seem to refer to the career of the novel's hero, insofar as it is reported here, but that is not correct. Quite aside from the fact that Paul Pennyfeather ends up where he began, at Scone College, Oxford, with nothing to show for his adventures beside a "heavy cavalry moustache," there is a picture of an English society that is clearly in recession. Knaves and idiots have taken possession of everything, and avoidable catastrophes strike down the innocent. A culture of apologetic personal irresponsibility has taken root. It is unsafe to be around grand people, because in their carelessness or contempt they will put you in harm's way. Everyone seems to be equipped with just enough knowledge to be dangerous to his fellow man. Now, how could this be funny?

Waugh commands several literary devices with Napoleonic efficiency. The skill that comes first to mind is a sense of the preposterous. Waugh knows just how far to go. At the start of the novel, poor Paul intersects with some extremely drunk lords, and in the encounter he loses his trousers. Thus he is seen dashing across the quad in a disrobed state, and therefore he must be sent down. Given the disgrace of expulsion, his trustee is entitled to refuse to advance any of the money that is rightfully his. Given Paul's blamelessness, this outcome is outrageous, but it is also a preposterous consequence of a midnight skirmish. It is not realistic, and we love having our leg pulled a little. Waugh never pulls too hard.

Continue reading about Decline and Fall at Portico.

Posted by pourover at 12:00 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

July 05, 2005

Pygmalion

It has occurred to me that a work of art that I take for granted is not as widely familiar as it used to be. Known by two names, Pygmalion and My Fair Lady, this comedy, created by George Bernard Shaw and adorned with songs written by Jay Lerner and composed by Frederick Lowe, is both highly entertaining and extremely illuminating. In the Greek myth, Pygmalion was a sculptor whose most beautiful marble came to life as Galatea. In the comedy, elocutionist Henry Higgins wagers that he can transform a guttersnipe into a lady, simply by teaching her how to speak. As befits such arrogance, he is confounded by his success.

You will ignore the film adaptation of the musical - except, of course, as a reflection of the stage musical's structure. It is a camp curiosity that dates from Hollywood's darkest hours. If you want to know what Rex Harrison was like in the role, watch Preston Sturges's Unfaithfully Yours, which will strike anyone who remembers the original Broadway production as a dress rehearsal for My Fair Lady. As for seeing what Julie Andrews was like, I can't say, because she was already out of the show by the time I got to see it, but I doubt that she was better as an actress than Wendy Hiller is in Pygmalion, the 1938 adaptation of Shaw's play. Shaw himself worked on the screenplay, and the whole business was authorized by him. Leslie Howard is quite good enough as Henry Higgins to put Rex Harrison out of your mind, at least for as long as he's on screen; he's a craftier, geekier Higgins, and he is more obviously vulnerable to the surprise of love than Harrison's good doctor does.

You will also read the play, because Shaw's stage directions, which often seem to equal the word-count of the dialogue, will help you to bring the play to life. Theatre people, who regard the stage directions as a frightful usurpation by the playwright of other professions' work, don't understand how hard it is for the general reader to read a play. Here's a brief sample:

Mrs Higgins [calmly continuing her writing] You must have frightened her.

You can imagine how directors feel about such poaching. But never mind, it's part of the fun of the play for you.

Notwithstanding the great fun of the piece, Pygmalion is entirely without farcical complication.

Continue reading about Pygmalion at Portico.

Posted by pourover at 12:00 AM | Comments (1) | TrackBack

May 12, 2005

The Black Spot

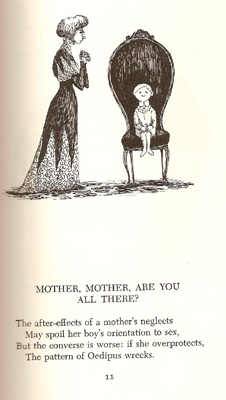

You're stuck inside Fahrenheit 451 . Which book do you want to be? Without a doubt, Felicia Lamport Kaplan's Scrap Irony (Houghton Mifflin, 1961). This would oblige me to memorize, in addition to the cleverest verses in English, a host of drawings by Edward Gorey: each poem is illustrated! There are several very dry prose pieces as well, including an essay on telephone number mnemonics that I used to think was the funniest thing not written by Robert Benchley. The page that I've rather illicitly scanned shows Kaplan at her deadliest.

One section of the book, "Vice Verses," consists entirely of slightly naughty poems involving words that have been stripped of agglutinated prefixes. Exempli gratia:

Gregious Error

Many a new little life is begot

By the hibited man with the promptu plot.

or (from the facing page)

Royal Lemma

His ministers urged the young monarch to wed,

But he viewed their proposal askance

When they said that the only girls suitably bred

Were his nieces and cousins and aunts.

He rejected all these with a touch of impatience:

"Not one will I have for my queen;

I think it immoral to wed one's relations;

I much prefer cest - it's so cene."

There are many other treats, but we had better press on.

Have you ever had a crush on a fictional character? I was very taken by Glencora M'Cluskie, future Duchess of Omnium, the first time I went through Trollope's Palliser novels, and I reread Marquand's B.F.'s Daughter just to spend time with Polly Brett. On the whole, though, I find romantic entanglements distracting. I am already very involved with my wife.

The last book you bought was...? Gee, let's see what Amazon says. Ah, here it is. Home Land, by Sam Lipsyte. It's in the mail. This is the third book (at least) that I have bought after reading about it at BookLust.

The last book you read was...?That's very easy, because I just finished it yesterday. Elizabeth McKenzie's Stop That Girl. (The second book, at least.)

What are you currently reading? Incognito, by Petru Dumitriu. Correctly or not, I recall this as the first new, clothbound novel that I ever bought. I don't know when it appeared in the United States; the copy that I fished out of Alibris is the Collins edition of 1964, translated from the French by Norman Denny. Dumitriu was a Rumanian expatriate whose portrayals of his homeland before, during, and after World War II are both beautiful and powerful; I have never encountered a more sickening account of life as a communist apparatchik.

Five books you would take to a desert island... Emma, my Pléiade edition of Racine's plays, The Golden Bowl, The Sun King, by Nancy Mitford, and Vile Bodies, by Evelyn Waugh. (If I got to take a sixth, it would be their correspondence.)

Who are you passing this stick on to and why? This is a tough one, because all my candidates are too busy. So: forgive me, Biscuit (I'm curious), Coquette (ditto), JR (I need some new French writers to follow), and Ms NOLA (can you ask?).

Posted by pourover at 03:54 PM | Comments (1) | TrackBack

April 20, 2005

Dawn Powell: A Time To Be Born III

This reading journal has been interrupted by a succession of active days on which, if I looked at A Time To Be Born at all, it was out and about or late at night. I polished off the book in two sittings, yesterday and this morning, but, again, thanks to those busy days, I really didn't have the energy to think about writing. Because I'm terrible about taking notes when I read, I can't even offer a sampling of choice plums from the text. I hope that I've written enough anyway to make you think about reading the novel.

The second half of A Time To Be Born is a record of Amanda Keeler's downfall. Having snagged Julian Evans and flown off on his media empire to fame and fortune, Amanda feels a fatal itch for emotional excitement. (It would be terribly wrong to call this a search for love. Amanda is a profound narcissist.) Giving in to the itch is the mainspring of the plot, because it presently brings Ken and Vicky together, while heaping complications on Amanda's schedule.

As the nation moves closer toward war, charity belles like Amanda go out of fashion and are replaced by women in uniform. Amanda flourished in the twilight of isolationism, but didn't have the sense to see that real war would make her redundant. Powell doesn't cover this very extensively, because her primary interest is not the transitory nature of celebrity, and she wants to demonstrate that Amanda wrecks her own life.

Alongside Amanda's downfall, Powell amuses us with the deepening of feelings between Vicky and Ken. the amusement lies in Vicky's belief, almost to the end, that Ken is too much in love with Amanda ever to turn his affection to her. Powell's handling of this particular course of love is somewhat unusual. It begins with Vicky's calling Ken to tell him that she's moving out of Amanda's studio - a step that causes Amanda to break with her in a tumultuous outburst at an Evans dinner party - and into her own little apartment on 13th Street. The next thing you know, she's in bed with him at his flat. His reappearances are all vaguely incoherent - he's usually drunk. Eventually, Vicky decides that she's going to fight for him, but her resolve is shaken to its foundations when Amanda turns to Vicky for help with an abortion, and pleads, afterward for a visit from Ken. It is all very end-of-Traviata and all very fake, because even before Ken arrives (and he only very reluctantly agrees to come), Amanda has learned of a prospective date with the great writer, Andrew Callingham, the only man whom she acknowledges as her literary superior. When Ken arrives, Vicky is gratified to see that he doesn't even look to see if Amanda is in the room. But the narrative dispenses with open avowals of love until the very last page - even though by that point Vicky and Ken are already married. The "happy ending" carries a fine sting:

Ken kissed her.

"You're the only one for me, darling. There couldn't ever be any Amanda in my life, now that I know about you. Never, never, again."

Vicky stroked his hair.

"Thank you for that, darling," she said gratefully.

But she was not at all sure whether he was speaking the truth or what he hoped was the truth.

For that matter, neither was Ken.

This is really only a reality check: for the moment, Ken and Vicky plan to be as happy as they can be together, and that's really all anyone can ask. Begrudging the reader the glowing satisfaction of having the newlyweds enter the parallel universe of improbable romance, however, is one of Powell's many faintly rebarbative habits.

This finale is preceded by a jovial scene in which Rockman Elroy, the wily uncle, makes up his mind to marry Vicky, because she's the ideal listener. Terrified, she has always listened to his abstruse descriptions of "scientific" problems with a prettily expectant smile - one that assured him that she was never going to say anything in reply. He arrives at Vicky's apartment to find Ethel Carey cleaning it out. The vignette is the droll cap of a story that begins in Chapter X. Vicky has been invited to dinner at the Elroys'. Impatient with being presented to one and all as the friend of Amanda's Keeler Evans, Vicky tells Nancy that she and Amanda are friends no more, and in the telling of Amanda's outburst about Vicky's leaving the studio, the true nature of her relationship with the great woman tumbles out, and the Elroys are dismayed to discover that they've been entertaining a charity case of low background. Then, at the dinner table, Mrs Elroy makes it clear that her contempt for Hitler is purely social: "The Kaiser was at least a gentleman."

The picture of Hitler as a musical hoodlum was the only appealing thing Vicky ever heard about him, but this vulgar unconventionality seemed to have around the Elroy political conscience as no other atrocities could, and Mrs Elroy went on in this vein, repeating what a cousin of an attaché in Germany had told her personally about Hindenburg's dinner for his new Chancellor years ago, when all the ambassadors simply ignored the upstart, who did not know his way around among the noble glasses and cutlery, and who was snubbed by every one naturally, since in those days no one ever dreamed the common people would consent to be led by a wrong-for-user, a café-sitter.

So that's why people like the Elroys are against Hitler, Vicky thought, getting angry. They would stand for any barbarism but mean birth and bad manners, and it was a cruel trick for them to make a Cinderella of the monster just by their contempt for him. How dared people like the Elroys and Julian Evanses be on our side, besmirching it with their snide reasons? Making country club of a great cause, joining it only because its membership was above reproach, its parties and privileges the most superior, its officers all the best people? Why didn't they stay on the oppressor side where they belonged and where their tastes actually were? They did in the Spanish War, and for the same reasons that they switched over in this war. Vicky was aware of a wave of indignation brining unexpected strength to her spirits.

"You don't object to cannibalism, then," she said. "It's the table manners they use, isn't it, Mrs Elroy."

Uncle Rockman was staring at his sister-in-law with a peculiar hostility.

It's as though the matron has just been exposed to Rockman for what she is, and presently he is tearing out of the suite. When Vicky follows, a friend of Uncle Rockman who happens to be present tells the Elroy ladies that Rockman is sweet on Vicky.

The story is picked up in Chapter XI. The Elroys are in a constant state of lamentation, having allowed an cunning adventuress into their home.

Mrs Beaver Elroy had never in her whole fifty-one years been so distraught as she found herself on learning of her brother-in-law's sinister plans against her happiness...

She had counted so completely on this graceful flowering of her connection with Rockman that she now felt as betrayed as if vows had been exchanged, and it was hard to remember that Rockman had never encouraged any such hopes. It had begun almost at Beaver's funeral. After the children grew up and married, then she would turn to the waiting Rockman and say, "Now, Rockman. Now is our reward."

That Vicky wouldn't marry Rockman under any circumstances - that she is hopelessly in love with another man - never crosses the ladies' minds, because they're too thrilled by the awfulness of their betrayal, which is, of course, essentially financial. Mrs Elroy screws up her courage and makes an appointment with Amanda, hoping that the celebrity will intervene and peel Vicky away from Rockman. Amanda, rather fabulously, agrees to talk to Vicky - and that's that.

The interview was over, but it took Mrs Elroy, unused to such harsh business manners, a moment or two to realize the fact. She had expected to have a little polite chat to cover up the crude purpose of her call, but Amanda would have none of it. She stood in the doorway, unsmiling, uncivil, really, Mrs Elroy thought, until the latter had collected her gloves and bag. Amanda rang for some one to see the lady out, and waiting beside the elevator, looked sharply at her guest.

"It's your brother-in-law, not your brother, isn't it? she asked.

Mrs Elroy nodded.

"About your age, you said," Amanda pursued, reflectively. "Oh, Now, I see."

The implications of what she saw made Mrs Elroy's susceptible nose assume a delicate heliotrope shade, and shattered for the moment her satisfaction in the interview. Mrs Elroy shuddered as she felt the heavy doors of Twenty-nine swing shut behind her, thinking of Amanda's cryptic "Oh, now I see." She had not said a word to suggest such a thing, but after all her trouble Amanda had merely thought the lady was anxious to get Rockman for herself. Walking gracefully down Fifth Avenue the liquid spring air revived Mrs Elroy's confidence. It didn't really matter what Amanda thought if she could restore Rockman to his rightful owners. Yes, she really had accomplished something.

But that sense of accomplishment is all liquid spring air, and the Elroys disappear altogether, but for Uncle Rockman's brief boulevard-farce scene toward the end.

Amanda's chute follows a more melodramatic trajectory than one might expect. The material and Powell's handling prepares one for a Waughian machine infernale, and Powell certainly lines things up for an automatic self-destruct. Amanda loses Miss Bemel's loyalty, and no one will tell her that Julian has taken to visiting the first Mrs Evans at her estate on the Hudson. Vicky and Ken are dangerous enemies. But the unraveling of Amanda's glory is a matter of dumb miscalculation.

Julian, disturbed by Amanda's independence, and her refusal to go to bed with him, has hired a detective, Mr Dupper. The horror of Mr Dupper's ugliness is lavishly described in Chapter XIII, but you'll read it for yourself, and once is enough. Having been filled in by the gumshoe (who seems to be more of a thug), Julian decides to have it out with Amanda. When she waltzes in from an afternoon and evening at the Waldorf, spent trying in vain to be alone with Andrew Callingham, who is leaving for Libya the next day, Amanda is taken completely by surprise by Julian's ferocious dismissal. He orders her out of the house at once, and, quite at sea, she heads for Twenty-One, where she knows she'll find Callingham, and throws herself upon his mercy. It has been clear from the outset that while he may allow himself to be entertained by Amanda, he is never going to submit to her, but her vanity is too colossal to concede this point. Back at the Waldorf, she offers to sleep with him.

He burst out laughing.

"Fine. I never pass up a pretty gift like that. I won't change my mind about anything, though."

"It might," Amanda said, tossing her head.

"The talk is that you're no good in the hay, my dear," Callingham chuckled. But I like to be open to conviction."

It might still work, Amanda thought, just as it had with Julian. With this farewell memory she could count on winning him over completely when she reached him in Africa. This was the way she had planned it and this was the way it would have to be. Unless, for the first time, something went wrong for her. Unless he was a stronger man than she. Unless he, in his own egotistical way, had other plans. Unless Julian really could put a hex on her.

Even under Callingham's rough embrace there came, along with her usual annoyance at the damage to her permanent, Amanda's first doubts.

And that is the end of Amanda. She goes to Libya, we're told, but she doesn't snag Callingham. And after that, the signal of her celebrity vanishes altogether.

Is Dawn Powell heartless? Not at all. She's a realist. We're flawed mortals trying to make the best of a vale of tears, and what goes around comes around. She is merciless about pretentiousness and the delusions of vanity. She is a collector of rationalizations on par with Anthony Trollope, but there is no innocence in her novels, just ignorance and inexperience. At the same time, she does not seem to have a sense of America as a special place. It is a swath of the world like any other, and nobody is truly, truly grand. Her belief that everyone is to some extent on the make, if not on the take, is cynically European, but the foreigners in her books are good and bad in the same way that everyone else is good and bad.

There is an unmistakable sense, in Dawn Powell's books, of presenting the minor follies of the lady's life as material fit for serious fiction. It is a difficult stunt to pull off, because these follies are indeed very silly and pointless, and they confirm all the patriarchal animadversions regarding the inferiority of women. That women are not to be trusted is yet another retrograde feature. The old idea that women are incapable of true friendship is repeatedly evidenced. But men are in no sense superior. They may be indispensable, for all the usual reasons, but they tend to become as fatuous as they are allowed to be. In the end, your pleasure in Powell's books is modulated by your reaction to the whiff of unrealized ambition. This wouldn't be because Powell set her sights too high. It's rather that the comedies of manners that entertain don't play out according to the formulas that we're familiar with, while at the same time failing quite to establish new rules. If anything, she did not set her sights to the level of her ability. And there is no gainsaying that her vernacular is jarringly inelegant at times.

But, as I said, she's great fun to read, even when she's heartbreaking.

Posted by pourover at 07:41 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

April 14, 2005

Dawn Powell: A Time To Be Born II

I