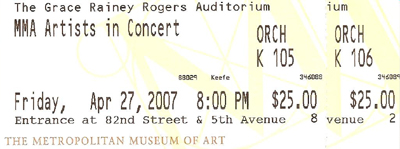

Last Thursday night, Thomas Meglioranza gave a recital at the

Thalia at Symphony Space. When I got there, I wished I'd brought a camera,

because Tom's name was running around in lights on the marquee ribbon. The recital,

sponsored by the Concert Artists Guild together with Symphony Space, featured

pianist Reiko Uchida and violinist Jessica Lee.

As the intriguing postcard announcing the recital made clear, the program

would consist of works by living American composers. Not too long ago, it would

have taken several earth movers to get me to show up for such an event. Most of

the contemporary American music that I've heard is either jazz-inflected, which

is agreeable but something of a cop-out, or blandly aimless and anodyne. On top

of that, it is so often in English! Which, when it comes to full-throated

singing, is a language that I grasp only with difficulty; German and Italian are

so much more intelligible, even if I don't know what the words mean. But if I

was happy to go to Tom's recital, it wasn't because I'd be doing him any favors

by padding out the audience. I've learned, in the past year, that Tom

Meglioranza is an exceptional singer with a very strong gift for performing

(among other things!)

music by living American composers.

What I didn't expect (aside from Tom's name in lights) was a brilliantly

composed program. I don't mean that it was perfect. But it was built to grow, to

cultivate over what I hope will be a long and fruitful career. I have never

heard another singer (no, not even Dawn Upshaw) with Tom's ability to render art

songs the respect that is their due while making them not only thoroughly

approachable but really great to hear. You can check your sense of duty at the

door and trust that Tom will entertain you. How does he do

it? The short answer is that his commitment to the music is total. The beautiful

voice, the skilful execution, the personal charm - these are all very well, and

Tom has them in spades. But he believes in what he is singing. Perhaps it would

be more helpful to say that his voice believes.

The program began with "The Pregnant Dream," by Aaron Jay Kernis, who also

composed the last work on the program, "A Song on the End of the World." "The

Pregnant Dream," which I'd heard Tom sing at the Naumburg competition last

spring, sets a droll poem by May Swenson.

I had a dream in which I had a dream,

and in my dream I told you,

"Listen, I will tell you my dream,"

And I begin to tell you. And

you told me, "I haven't time to listen while you tell your dream."

Mr Kernis's setting turns the much-repeated word "dream" into a humorously

maddening ostinato - humorous because, in the dream, the dreamer couldn't

remember the dream. This a capella number hides its virtuosity with a

smile, and it was the perfect opener to the recital that followed.

David Liptak's Under the Resurrection Palm is a set of three songs to

verse by two poets, Linda Pastan and Rita Dove, for voice and violin.

Unsupported by a piano, the voice sounds vulnerable next to the violin, and that

suits the poetry very well. "The Bookstall," a bibliophile's fancy run loose,

but finding a serene climax in the line, "every book its own receding horizon,

was my favorite here. Next on the program - Ms Uchida, the gifted accompanist

with whom Tom works when he can, made her first appearance here - was Russell

Platt's The Muldoon Songs, setting four poems by Irish poet Paul Muldoon.

Once again, I was treated to the second performance of something that I'd heard

at the Naumburgs (the cycle's first song, "Cuba"). The Muldoon Songs and

Into the Still Hollow, by John Rommereim - the music that followed - were

the only items in the program that seemed ordinary to me. Mr Rommereim's setting

of WS Merwin's poem is a set of seven linked monologues, delivered by archetypal

characters ("King," "Scholar," and so on), each one ending in the Latin tag, "Et

ecce nunc in pulvere dormio." I did not find enough distinction between these

characters, and if it hadn't been for the Latin, I wouldn't have known where one

stopped and the next began. But I suspect that I was alone here; the audience

clearly liked both the Platt and the Rommereim.

After a brief pause. Tom sang a bitter song by Milton Babbitt, "The Widow's

Lament in Springtime." Its text, by William Carlos Williams, compresses a

widow's grief into an inability to delight in the blossoming of her beloved

fruit trees. Love and death are not mentioned, making the sense of loss as stark

as Mr Babbitt's music, which is sore beyond regret. Arresting on its own,

"Lament" prepared the audience for The Plundered Heart, a set of two

songs written by Jorge Martín and commissioned expressly for Tom. This was the

dramatic high point of the evening. The poems, by JD McClatchy - "Fado" and

"Pibroch" (Portuguese and Scottish folk forms, respectively) - follow the

anguish of jealousy with the numbness of loss. The piano writing never shakes

off the beating heart that constitutes the startling image of "Fado"; in

"Pibroch," a low-throbbing pulse alternates with chords of Celtic placidity - a

placidity that, having nothing to do with the sentiment of the text, powerfully

underscores the lover's hopelessness. (It shouldn't work, but it does.) I was as

wrapped up in all of this as I've ever been in any opera, and deeply shaken when

it was over.

Derek Bermel's Nature Calls is a set of three delightful songs, to

verse by Wendy S Walters, Sylvia Plath, and Naomi Shihab Nye. "Spider Love" is a

wicked vamp on an ancient theme (don't say you weren't warned about romance).

"Mushrooms" rather fearfully announces the conquest of the earth by stealth:

"Our foot's in the door." The final song, "Dog," is a barcarolle that

compares the sky to the belly of a sleeping canine; it couldn't be gentler. Mr

Bermel's vocal line was perhaps the most dynamic of any of the songs; it had

something of the spunk of Ned Rorem's jauntier pieces.

Aaron Jay Kermis's "A Song on the End of the World," for voice, violin, and

piano, sets a poem written by Czeslaw Milosz in 1944. A hauntingly arched phrase

violin phrase brackets the song's decidedly unapocalyptic meditation on final

things that, musically at least, has it two ways - beautiful music for an

ominous proposition. It was the perfect formal close to the recital. As an

encore, Tom sang Stephen Foster's "I Dream of Jeanie," to accompaniment written

by Ned Rorem. Oh, what a difference Mr Rorem's accompaniment makes! Instead of

the sugary chords and curlicues that nineteenth-century practice would dictate,

the piano sets the voice free with a string of loose, wide-ranging arpeggios.

The recital absolutely at an end, all I could think of was a line from

Wallace Stevens's "Credences of Summer":

This is the barrenness

Of the fertile thing that can attain no more.

The barrenness was in my ears; I could hear no more music that night.