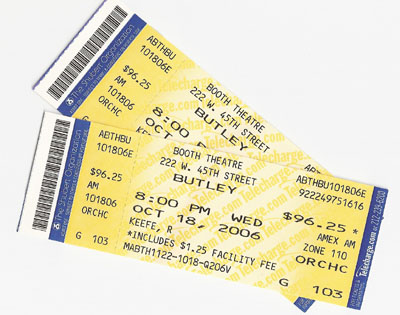

In which we have a look at this week's

New York Times Book Review.

There's a lot of fiction this week, but the strong reviews are

on the other side of the divide, with no less an eminence than Henry Kissinger

reviewing the new book about Dean Acheson. Daniel Mendelsohn's review of The

Discomfort Zone is, in contrast, a disgrace to the Book Review.

I'll bet that Sena Jeter Naslund and her people didn't expect

her Marie Antoinette book to be covered in the Review.

Fiction

One of the small payoffs of reviewing the Book Review is

learning what to expect of certain reviewers. Erica Wagner, literary editor of

The Times of London, is either nasty or unsympathetic in three of the

four reviews that she has contributed to the Review since I started

paying attention; either way, she is never entirely intelligible. Make that four out of five. Her review of Edna O'Brien's

The Light of Evening is unsympathetic. The review is a mix of storytelling and slapdown. It is

also useless.

Elissa Schappell does a little better by Joyce Carol Oates. She

storytells Black Girl/White Girl for a few paragraphs before settling

into what one feels is the inevitable judgment.

By now, it's a cliché to comment on the

rate at which Oates turns out books, making Trollope look as if he was

writing in handcuffs. Still, this one feels rushed to a conclusion.

Meg Wolitzer's review of "''old fashioned' novelist" Edward

Bausch's Thanksgiving Night is itself somewhat old-fashioned.

... Richard Bausch displays a bracing, unapologetically

old-fashioned sensibility. Using the time-honored tradition of putting a

holiday in a strategic narrative position, he shows us the insular,

byzantine world of a family and its assorted friends and neighbors in the

fictional town of Port Royal, Va, on the way to "the last Thanksgiving of

the century."

That, together with a nice

chunk of writing from the novel itself - which Ms Wolitzer does not include -

would really be all the review anyone needed. Myla Goldberg gives Chris Adrian's

The Children's Hospital a glowing, if qualified, review. The novel takes

place in the future and conjoins science fiction with magic realism.

A literary work that employs the supernatural must allow magic to

further its ends without permitting it to hijack the boat. The Children's

Hospital manages this at the outside, but stumbles further on. .... In

Adrian's attempt to paint the big picture, depth of character is too often

sacrificed.

But Ms Goldberg hails "the

exciting process of watching a talented and original writer gain mastery of his

powerful gifts."

Moral Disorder: Stories is the latest book from Margaret

Atwood, and reviewers have generally detected an autobiographical element in the

collection, as if Ms Atwood were summing up a lifetime for a change, instead of

imagining apocalypses. Alice Truax writes, instead,

Atwood is coy about the stories' relationship to one another in a

way that proves slightly tricky for the reviewer but stimulating for the

reader. They aren't explicitly about the same woman at different stages of

her life, but - as one gradually, tantalizingly realizes - they could be,

and the fact that the collection is studded with references to doors and

tunnels is hardly accidental. The first time through, then, its heroines

lean in toward one another, reaching out to clasp hands as the reader

stumbles over bits of their shared history. ... Upon rereading, however, one

is struck by the stories' integrity - and how different these girls and

women are from who they wee or who they might later become ... Atwood's

reticence gestures toward the fractured nature of identity, and how swiftly

that identity can change.

Ms Truax gets

top marks for conveying a sense of what reading Moral Disorder might be

like.

I suspect that Steven Heighton could have used more space for

his review of Sebastian Faulks's Human Traces, an historical novel in

which a Frenchman and an Englishman tie up to approximate, so to speak, the

career of Sigmund Freud. The telltale sentence comes at the end of the review.

Although Human Traces is beset with problems, the novel is

no failure. A generosity of vision, an integrity of intelligence and feeling

lift it above the level of its own elements.

We oughtn't to have to take Mr Heighton's word for it. Instead of storytelling

Mr Faulks's three-decker plot (and making it sound somewhat ridiculous in the

process), Mr Heighton ought to have focused on that "integrity of intelligence

and feeling," taking care to provide us with corroborative passages from the

novel.

Geoff Nicholson's bemused review of Giraffe, by J M

Ledgard, is one of the more entertaining pieces in this week's Review.

Nobody is going to accuse J M Ledgard of lack of ambition, and in

an age of timid and modest novels this is a virtue. The book is often

overwritten and sometimes pretentious, but Ledgard is an interesting and

serious writer, and his book remains in the mind, even if you don't entirely

want it to. I was continually reminded of Harold Bloom's remark about all

great books being strange: Ledgard has certainly got half the equation

right. I can safely say I've never read anything like Giraffe, and,

on balance, and it's a fine balance, I think I mean that as a compliment.

Mr Nicholson notes that Mr Ledgard's improbable tale is in fact based on actual

events.

Finally, there's Bedlam, by Craig Hollingshead, another

historical novel. Andrew Sean Greer's judgment is clear:

Hollingshead's elegant, heartfelt writing and smart research

almost make up for the novel's oddly static feeling. The author seems too in

love with the past to be willing to take liberties with it.

A new novel about Marie Antoinette, reviewed together with a new book about the

queen's wardrobe, will be mentioned below.

Nonfiction

This week cover goes to former Secretary of State Henry A

Kissinger's review of Dean Acheson: A Life in the Cold War, by Robert L

Beisner. Mr Beisner has every reason to be happy with the review, as might the

shade of Acheson himself.

Acheson emerges from the Beisner book as the greatest secretary

of state of the postwar period in the sweep of his design, his ability to

implement it, the extraordinary associates with whom he surrounded himself

and the nobility of his personal conduct.

Mr Kissinger ends the review with a discreet finger-wave at his current

successor and her boss. John Leland gives a grudgingly admiring review to

Through the Children's Gate: A Home in New York, Adam Gopnik's latest

collection of essays. "He is at times too good a writer, but never less than an

acute reader," writes Mr Leland. Too good a writer?*

Bill Bryson has added The Life and Times of the Thunderbolt

Kid: A Memoir to his shelf, and Jay Jennings gives it a very favorable

review that is not short on judgment.

As a humorist, Bryson falls somewhere between the one-liner

genius of Dave Barry and the narrative brilliance of David Sedaris. He's not

above sublime low fat and feces jokes, but at his best he spools out

operatically funny vignettes of sustained absurdity that nevertheless remain

grounded in universal experience. These accounts, like the description of

the bumper-car ride at a run-down amusement park or the tale of a friend's

father's descent from the high dive at a local lake, defy excerpting; when

taken whole, they will leave many readers de-couched.

Elizabeth Royte, whose last book was about garbage disposal,

praises Colin Tudge, author of The Tree: A Natural History of What Trees Are,

How They Live, and Why They Matter, for taking a "sudden and uncompromising

political turn" toward the end of his interesting book. "Tudge is courageous to

take this stand and risk alienating readers who've stuck with him throughout

solely for the love of trees and his enchanting way of writing about them."

Jacob Heilbrunn reviews Hubris: The Inside Story of Spin,

Scandal, and the Selling of the Iraq War, by Michael Isikoff and David Corn

with judicious storytelling - one of the few instances that hasn't made me

complain.

They show that in many ways the administration became the dupe of

its own propaganda. Though their narrative spins out of control by the end,

much of the book makes for fascinating reading.

Although "fascinating" wouldn't be my word. A few pages later,

The

Architect: Karl Rove and the Master Plan for Absolute Power, by James Moore

and Wayne Slater, gets rather less sympathetic treatment by Nicholas Confessore,

who asks, not unreasonably, why we go on thinking of Karl Rove as a big success

when the administration and even the Republican Party are so beleaguered. "The

authors depict the decline in Rove's fortunes toward the end of their account,

but they never really square it with their belief in his near infallibility."

On facing pages, we have Louis XIV and Marie Antoinette.

Antonia Fraser's Love and Louis XIV: The Women in the Life of the Sun King

gets a pass from Megan Marshall, who somewhat ungraciously fails to mention

Nancy Mitford's evidently better book. "While Love and Louis XIV doesn't

quite measure up to the high standards of synthesis and narrative propulsion of

her best work, the book is still entertaining and instructive." Liesl

Schillinger takes on Queen of Fashion: What Marie Antoinette Wore to the

Revolution, by Caroline Weber, and a novel,

Abundance: A Novel of Marie

Antoinette, by Sena Jeter Naslund. Ms Schillinger really likes the former:

In Queen of Fashion, her suspenseful, remarkably

well-documented and surprisingly humanizing account of the role style played

in Marie Antoinette's fate and legacy, Caroline Weber, who teaches at

Barnard College and is an expert on the Terror, adds texture, shimmer and

dept4h to an icon most of us thought we knew already.

Perhaps because of the coincidence of Sophia Coppola's film's release, Ms

Schillinger is permitted some almost egregious storytelling about Marie

Antoinette, going on for three lengthy final paragraphs, la nuit de Varennes

included, while making just one small reference to Ms Weber's book. As to Ms

Naslund's offering, it merits two sentences overall, with a reference to Barbara

Cartland in the first and another to Forever Amber in the second.

It's no surprise that Douglas Brinkley indulges in a lot of

storytelling in his review of Johnny Cash: The Biography, by Michael

Stressguth, but his sins are partially redeemed by clear judgment.

What makes this so valuable a biography is that Streissguth, an

associate professor of English at Le Moyne College in Syracuse, debunks the

myths that have enveloped Cash. ... Although Streissguth is not the literary

equal of Peter Guralnick (Elvis Presley) or Elijah Wald (Robert Johnson), he

avoids the gush-and-awe of Rolling Stone and Spin. ... The

amount of new archival material he unearths, however, is truly impressive.

Virginia Heffernan is vastly less taken with A Futile and Stupid Gesture: How

Doug Kenney and National Lampoon Changed Comedy Forever, by Josh Karp. Ms

Heffernan all but dismisses the book with a sigh of "You had to be there." She

does suggest that Kenney was one of those whose people, to understand whose

"allure," "Maybe you had to know them." Equally telling, however, is her praise

of a writer who she feels is somewhat shortchanged by Mr Karp's book, P J

O'Rourke. She writes that he is "more reliably funny" than his old colleagues.

Yes, but only if you like really sour humor.

I have saved for last Daniel Mendelsohn's totally inexcusable

hatchet job on Jonathan Franzen's The Discomfort Zone: A Personal History.

Anybody who follows this blog knows that I'm an admirer of Mr Franzen and his

work, and I would take issue with Mr Mendelsohn's judgments wherever they

appeared. But they do not belong in the form of a book review in the Book

Review. Mr Mendelsohn is attacking not so much a book here as a line of

thinking about personal writing. The Discomfort Zone is a pretext for Mr

Mendelsohn's distaste for something else altogether, and his piece is strewn

with hints at what this might be. For one thing, he has not one entirely

positive statement to make about the book. The sheer implausibility of such a

dismissal suggests that ideology of some kind is at work. And he is also pretty

mean, not about the book but about the author.

"Almost every young person experiences sorrows," he rightly

points out at the beginning of his exegesis of Peanuts - a sentence

that gives you hope that the geeky child still hiding in the adult Franzen

is going to admit that, like everyone else, he loved Peanuts because

he, too, identified with the perpetual awkward, perpetually failed, and yet

just as perpetually optimistic Charlie Brown. But no..."

This is bullying, not criticism.

Franzen, like most of us, is very likely an awkward combination

of Charlie and Snoopy; the difference being that whereas most of us

[emphasis added] think of ourselves as Charlie with a bit of Snoopy, Franzen

clearly doesn't mind coming off as a whole lotta Snoopy with the barest

soupçon of Charlie: a person, as this lazy and perverse book demonstrates,

whose very admissions of weakness, of insufficiency, smack of showboating,

of grandiose self-congratulation. For my part, I'll stick with Charlie. Who,

after all, wants the company of a character so self-involved he doesn't even

realize he's not human?

Mr Mendelsohn is

too old for this sort of gleeful savagery. He ought to know that, when you

really can't stand somebody, the best thing is to keep a distance. He is

entitled to be rubbed the wrong way by Jonathan Franzen. He is not entitled to

parade his evaluation of Mr Franzen's personal defects in the pages of a

national book review. This was a commission that he ought firmly and immediately

to have declined.

Henry Alford's "Essay" is yet another bit of pastiche: two

obituaries cut and pasted from those of famous writers, a (male) "Impossible

Author" and a (female) "Difficult Writer." Mr Alford has done better.

* Not that I don't know what Mr Leland is

"complaining about." I know of no writer who approaches Mr Gopnik when it

comes to making me despair of ever attaining mastery of this craft.