Book Review

In which we have a look at this week's New York Times Book Review.

Fiction & Poetry

First, the poetry. Eric McHenry doesn't like Dave Smith's Little Boats, Unsalvaged: Poems 1992-2004.

Immediacy may be what Smith is after, but he achieves very nearly its opposite - a halting, stilted speech that substitutes accumulation for arc, a sort of rhythmless repetitiveness for the "sentence-sounds" that mattered so much to Robert Frost. "A sentence is a sound in itself on which other sounds called words may be strung." Frost wrote. "You may string words together without a sentence-sound to string them on just as you may tie clothes together by the sleeves and stretch them without a clothes line between two trees, but - it is bad for the clothes.

That's a lovely image, Frost's is, and I'm grateful for the encounter. Mr McHenry does exploit his bad review of Dave Smith as an occasion to say some very nice things about the poetry of the late William Matthews.

David Orr, in "On Poetry," deplores the proliferation of poetry prizes. I'm not sure that I understand the full measure of his words, but I like this:

With the fading of transcendent ideals in certain areas of American life comes the inevitable fading of the dream of unsullied, undying art - and the nostalgic desire for prizes that remind us of that dream, if nothing else.

The occasion for Mr Orr's essay is a "Neglected Master Award," concocted by, among others, the Library of America. The first volume in this series (itself an award of sorts) goes to Samuel Menashe. The bit of verse that's quoted in the essay is very attractive indeed. Mr Orr notes that Mr Menashe belongs to the "austere Dickinsonian school."

There are seven novels this week. Collectively, the views make me wonder if there's a point to writing up novels just because they're new. Each of the reviews is more book report than critique, and each of them fails to quote enough original text for a reader of the Book Review to assess the novelist's command of sentence-sounds. Sam Lipsyte (author of Home Land) really likes Chris Abani's Becoming Abigail: A Novella, but instead of showing us why, he falls back on sketching the novella's (grim) story. Megan Marshall's review of A Million Nightingales, by Susan Straight, is equally enthusiastic and a little less lame in that it appraises Ms Straight's grasp of the race and gender issues that naturally rise in a story about a light-colored slave girl in antebellum Louisiana.

Straight's book is a deep consideration of the servitude all women experienced then - and, in some ways and some places, continue to experience even now.

But the bits of text that are quoted all function as book reports: evidence of plot points. Susan Cokal's review of Dara Horn's The World To Come is mystifying rather than interesting. The plot hangs on the provenance of a small painting by Marc Chagall.

No single character can unlock the secrets of the Chagall because the answers lie both too far back in history and too far into the future - the "world beyond" this life, which Horn depicts as a kind of ethereal mixer where old souls meet new ones, who learn from them before being born. This realm of the spirit is also the place where art may take us, and Horn offers sly reminders that we may not like what we find there.

This is all very teasing, but I don't have time to scratch my head over it. If I'm not puzzled by Andrey Slivka's review of The Woman Who Waited, by Andreï Makiine (translated from the French by Geoffrey Strachan), that's because I've read the novelist's first book, Dreams of My Russian Summers. Mr Slivka's book report makes the new book sound unintelligible. While it praises "the dreamy lusciousness of Makine's prose images," it offers only a pair of thumbnails, not quotes.

Three novels get short shrift (half a page - admittedly better than a roundup). Alexander McCall Smith, author of the No 1 Ladies' Detective Agency series (and other books), really likes Passarola Rising, by Azhar Abidi - and spends a surprising number of words saying just that. Comparisons to Candide are intriguing, especially as Voltaire turns up in this historical fantasy. Why does it sound like something that would make a better read in French? Dawn Drzal really likes Hilma Wolitzer's The Doctor's Daughter, but seems content to rely on fans who have already read Ms Wolitzer's previous fiction (Hearts and others) to generate their own enthusiasm.

In the only unenthusiastic review, Max Byrd is tepid at best about The Mercury Visions of Louis Daguerre, by Dominic Smith. He likes the first couple of chapters, but wonders why Mr Smith has changed so many of the facts in Daguerre's life and then observes that "Daguerre's compulsions never generate much urgency."

Aren't these reviewers being paid enough?

Nonfiction

On the cover this week is Alan Brinkley's frightened review of American Theocracy: The Peril and Politics of Radical Religion, Oil, and Borrowed Money in the 21st Century, by Kevin Phillips. There isn't anything in the review that regular readers of the Daily Blague won't have read right here, but it's nice to see that the alarm is spreading and perhaps getting louder. Mr Brinkley concludes thus:

There is little in American Theocracy that is wholly original to Phillips, as he frankly admits by his frequent reference to the work of other writers and scholars. What makes this book powerful in spite of the familiarity of many of its arguments is his rare gift for looking broadly and structurally at social and political change. By describing a series of major transformation, by demonstrating the relationships among them and by discussing them with passionate restraint, Phillips has created a harrowing picture of national danger that no American reader will welcome but that none should ignore.

Buy the book! And give it to someone who needs it when you're done.

Now we need a laugh. And Walter Kirn gives us one - a bushel, actually, in his review of Manliness, by Harvard Professor (of Government) Harvey C Mansfield. The review is acute and funny, and you've got to read it for yourself. But here's a little preview:

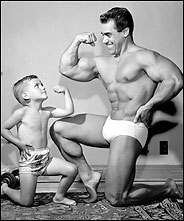

After a section on the history of "the great explosion of manliness that took place in the late 19th and early 20th centuries" (an image that gives even me, a straight man, erotic chills), it's time for Mansfield to stop preheating the oven and cook up the goose he's already got trussed and cleaned: the feminists.

The cheesy photo accompanying the review is wrong in so many ways that it's almost right. On the facing page, Budd Schulberg (author of What Makes Sammy Run) writes about Dave Kindred's dual biography, Sound and Fury: Two Powerful Lives, One Fateful Friendship. The two lives belong(ed) to Howard Cosell and Muhammad Ali. This certainly looks like the one sports book so far that it might be interesting (for me) to read, and in Mr Schulberg's opinion it's clear and candid, notwithstanding the author's friendship with the boxer.

A note at the beginning state's the author's intention: "My ambition was to recover Muhammad Ali from mythology and Howard Cosell from caricature." With the Niagara of words that has been pouring over these two superstars for more than 40 years, that's a heady assignment. But Kindred is up to it. Mission accomplished.

Another biography, Anna of All the Russias: The Life of Anna Akhmatova, by Elaine Feinstein, is everything that it oughn't to be. Olga Grushin holds it in such contempt that she won't use Ms Feinstein's translations of the poems - except to expose them as shoddy. Ms Grushin refers interested readers to Akhmatova's memoirs. Gossipy and hyperdetailed, the book "lacks depth."

When Akhmatova does step fully into the light, Feinstein seems primarily interested in her amorous entanglements. The chapter covering the mid-1920s - titled "Infidelities" - begins, "Amidst Russia's turmoil, Akhmatova was about to enter the longest and most intense relationship of her life."

Sniff! Of Elizabeth McCracken's review of Are You Happy?: A Childhood Remembered, by Emily Fox Gordon, I wasn't able to make a lot of sense. It appears that Ms Gordon looks back on childhood not as a story but as a sequence of moments, most of them "radiant" - notwithstanding some serious family problems. The secret: she was left to herself most of the time. Lucky girl!

Lucky guy Mike Mullane visited near outer space twice, and he writes about his experiences in Riding Rockets: The Outrageous Tales of a Space Shuttle Astronaut. Tom Ferrell likes Riding Rockets, not noting, however, that it's the sort of book that's usually "told to" a professional writer. He does give Mr Mullane high marks for respecting his female colleagues, but I'm not so sure that they would; Mr Mullane is simply a gentleman (or so he seems to be here).

Russell Shorto reviews Slavery in New York, a collection of essays published in conjunction with an exhibition at the New-York Historical Society. He singles out essays by Jill Lepore (on slavery in British New York) and Shane White (black popular culture) for high praise. Most New Yorkers were largely unaware of the city's engagement with slavery until the discovery of the African Burial Ground a few years ago. But this book and the show at the museum will bring home the awful truth to any of the unconvinced.

There are two books about the fight for civil rights under review. Historian Eric Foner has a few quibbles with Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice, by Raymond Arsenault. He feels that the data collected by Mr Arsenault ought to have been more deeply analyzed.

One wishes for a more detailed account of the riders' political backgrounds, organizational connections and later experiences.

Mr Foner appears to regard Freedom Riders as an exam that he (Mr Foner) is supposed to grade, and not a book that he is supposed to pronounce good or bad. On the facing page, Samuel G Freedman complains that Waiting for Gautreaux: A Story of Segregation, Housing, and the Black Ghetto, by Alexander Polikoff, is "overlong, poorly organized and plagued by clichés and corny puns, starting with the title." It's a story that Mr Freedman would have preferred to read about Gautreaux case in "as told to" format.

At the other end of the habitat scale, there's The Caliph's House, by Tahir Shah and reviewed by Adam Goodheart. Mr Shah is an English travel writer of Afghan extraction who bought a fixer-upper palace on the border of a Casablanca slum.

Writers are, far more than the general population, a high-risk category for the renovation virus. We can live and work almost anywhere, have a talent for blocking out inconvenient facts (like the slum next door) and are more than usually prone to delusions, not least those of grandeur. Couple this with a tenuous cash flow and the further delusion that we have an instinctive understanding of things like cabinet hardware, and the situation becomes positively dangerous.

And on top of that, we get a story out of the experience! Of Mr Shah himself, Mr Goodheart writes that he "is no negligible craftsman - with words, that is - and his somewhat predictable narrative is enlivened by well-wrought descriptions of life in Casablanca." In other words, a fine piece of "house porn."

Back to poverty: Virginia Postrel gives The White Man's Burden: Why the West's Efforts to Aid the Rest Have Done So Much Ill and So Little Good, by William Easterly, a good review. That is, she does her job, and makes clear that while Mr Easterly's critique of most aid programs is astute, "his alternative is undeveloped," and she gently explodes his distinction between "Planners" - whom he despises - and "Searchers." Searching for solutions to the poorer world's problems is certainly in order; ever since the Age of Discovery, the West has been telling the Rest what it ought to do. That's usually the only way we know how to offer help - at first. "At first" was five hundred years ago, and we ought to be doing better. Ms Postrel grades Burden favorably: it's an "important" book.

Just when you thought it was the last thing you'd want to read about, Rachel Donadio's Essay offers an interesting global survey of much-contemned new genre. In "The Chick-Lit Pandemic," Ms Donadio compares and contrasts contributions to the form from around the world. The Japanese and the French, she notes, haven't contracted a yen for it yet, but Indian readers and writers certainly have. Polish chick-lit - is this a joke? - often involve tragedies, while the Scandinavian version - no surprise here - displays anomie. South America doesn't even come up. Ms Donadio also provides a handy thumbnail of the chick-lit demographic:

20- and 30-something women with full-time jobs, discretionary income and a hunger for independence and glamour.

I just had to end with the photo from Walter Kirn's Manliness review. Why do I have the feeling that this photograph would get people in a lot of trouble today?